Forging a New Anglo-Japanese Partnership

Royal Ties Underpin New Anglo-Japanese Alliance

Politics History Imperial Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

British Archives Reveal Royal Friendship

Since leaving the European Union, Britain has demonstrated an unprecedented focus on its relationship with Japan. In September 2021, a British naval strike group headed by the nation’s newest aircraft carrier, HMS Queen Elizabeth, called on Japanese waters to conduct joint exercises with the US military and Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. One reason for this new closeness, of course, is to demonstrate reinforced cooperation in the face of China’s increasing reach, but the role of interroyalty exchange between Japan and Britain must not be discounted.

Britain and Japan are both island nations ruled as constitutional monarchies, and their respective royal families have enjoyed a relationship for around 150 years. I contacted the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle to inquire about any records they had regarding this special friendship. The archives hold files from King George VI’s personal secretary that include telegrams sent by the king to Emperor Hirohito, posthumously known as Emperor Shōwa, in 1940–41 to congratulate him on 2,600 years of Japan’s imperial line and on the marriage of Prince Mikasa, as well as a message of condolence on the death of the emperor’s aunt Masako, Princess Tsune. Telegraphic replies from Emperor Hirohito to King George were also displayed, confirming the close relationship between the two emperors.

New displays at the Royal Archives include:

- A draft of a telegram from King George to Emperor Hirohito congratulating him on the 2,600th anniversary of the imperial line on February 11, 1940, and a reply from the emperor to the king on February 12, 1940.

- A draft of a telegram from King George to Emperor Hirohito conveying condolences on the death of Her Imperial Highness Princess Masako, the sixth daughter of Emperor Meiji and wife to Prince Takeda Tsunehisa, on March 9, 1940, and the emperor’s reply of gratitude on March 11, 1940.

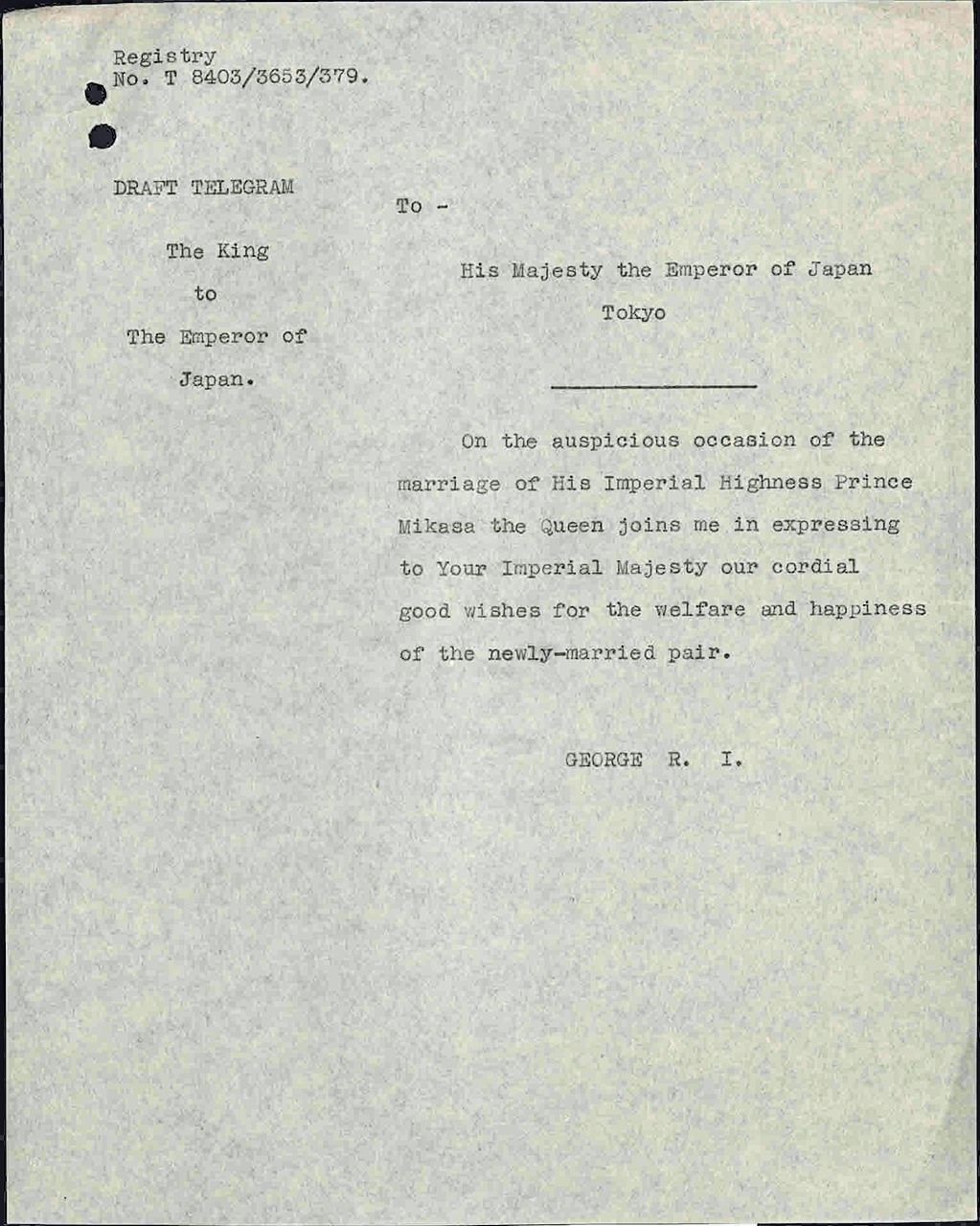

- A draft of a telegram from King George congratulating the emperor on the wedding of Takahito, Prince Mikasa, on October 22, 1941, and the emperor’s reply on that same day.

Of these, it is worth noting that the congratulatory telegram for Prince Mikasa’s marriage was sent only two months before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and began the Malaya campaign, touching off the Pacific War. The royalty of both nations engaged in friendly conversation until mere weeks before war made them enemies.

Draft of King George’s telegram of congratulations on the marriage of Takahito, Prince Mikasa, on October 22, 1941. (Possession of the Royal Archives; © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2021)

Showing the Value of Family Bonds

The connections between Britain’s royalty and the Japanese imperial household began in 1869, when Queen Victoria’s second son Prince Alfred visited Japan. Apart from one period during the war Japan’s imperial family members have looked to Britain’s royalty for hints on how to comport themselves ever since.

This friendship reached its peak during the reign of Emperor Shōwa. In 1921, when he was still crown prince, he became the first member of the imperial family to visit Britain. He left Yokohama on March 3 aboard the British-built warship Katori for a tour of five European nations. He returned six months later. His first, and longest, tour was of Britain. As it was only three years after the end of World War I, he made sure to visit the graves on Malta (then controlled by Britain) of Japanese sailors who died in a German attack in the Mediterranean Sea, as well.

At the time, King George V, Queen Elizabeth’s grandfather, was 55, while the crown prince turned 20 during his trip. The King took a paternal liking to the crown prince and offered him generous hospitality as they rode in the same carriage in a welcoming parade. During that trip, Crown Prince Hirohito learned the importance and warmth of family bonds from the modern royal family, as symbols of connection to their subjects. In 1979, while at the Imperial Villa in Nasu, the emperor reminisced that “The things I heard from King George V about constitutional monarchy’s nature became the root of my thinking for the rest of my life.”

Former Yomiuri Shimbun reporter Murao Kiyokazu wrote in an essay entitled “Kōtaishi no kekkon” (The Crown Prince’s Marriage) that at a press conference on his sixtieth birthday in 1961, the emperor recalled that the most enjoyable time of his life was his visit to Britain. “I went to Britain when I was twenty years old. I spent three days at Buckingham Palace with King George V, and he taught me alongside his son, the prince of Wales and future King Edward VIII, how to be a constitutional monarch. . . . I think of King George V as my second father.” Emperor Shōwa felt this kinship with the British royal family his whole life.

According to Eikoku ōshitsu shijiten (Encyclopedic History of the British Royal Family), King George V “remained a respected advisor to the Cabinet and secured his reputation as a successful constitutional monarch, a rarity in modern history.” He was a monarch who spoke directly to his government and took an active role in politics. King George V taught the young crown prince during his visit the principles of constitutional monarchy, in which the monarch is both a symbol and has the “right to warn“ as political intervention, and so the emperor invoked that right.

Anglicization of the Imperial Lifestyle

The visit also had a significant impact on the lifestyle of the imperial family. From 1923, not long after the crown prince’s trip to Britain, he began ordering suits from a famed tailor on London’s Savile Row, changing his outfits from traditional Japanese clothing to western formal wear. He also preferred ham, eggs, and toast for breakfast to the common miso soup and rice, and after the war he adopted what he had learned as the British style—oatmeal, coleslaw, and toast.

He also abolished the concubine system, a practice instated to increase the number of male heirs, in favor of monogamous imperial marriage. His reasons for introducing monogamy to the ancient, unbroken imperial line are apparently rooted in the lessons about modern family bonds and connection to the common people taught him by the British royal family during his trip. He even gave up sleeping in a futon for a bed. The family children were no longer raised by full-time caregivers but stayed together with their parents. This is how the imperial family became recognized as a true family among the people of Japan.

Japan and Britain signed a military alliance in 1902, as both nations recognized Russia as a common enemy. When Japan emerged victorious in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904–5, it was with British assistance. Later, though, the United States grew wary of the alliance as it watched Japan’s rise with apprehension, and pressed Britain to end it. At the founding of the League of Nations, Britain opposed Japan’s insistence on a clause denouncing racial discrimination in the covenant, and that in turn made Japan distrust Britain. Soon after the crown prince returned from his trip, in November 1921, he became regent, and the following month at a Washington conference, the participating governments decided to end the Anglo-Japanese Alliance as of 1923. Two decades later, in 1941, the Pacific War brought these nations into deadly conflict. Despite this, though, the crown prince’s three-week stay in Britain had served as a branching point in relations between the two nations.

Royal Ties Open the Way to Reconciliation

Communication between the two royal families only resumed after the end of the war. Distrust of Japan persisted in Britain, especially among former soldiers who had been imprisoned by the Japanese, but the British royalty and the Japanese imperial family managed to thaw relations.

In 1953, the year after Japan’s sovereignty was restored, Crown Prince Akihito made his first international visit to attend the crowning of Queen Elizabeth. The crown prince, who had learned the history of the British empire from Harold Nicholson’s biography of George V, was treated as a guest of honor by Prime Minister Winston Churchill. At a welcome luncheon, which included the owners of a popular newspaper that had once published anti-Japanese sentiments, the Japanese guest’s unpretentious personality made an impression on the British attendees, and relations between Japan and Britain began to improve.

In 1971, when Emperor Hirohito paid another visit to Britain 50 years after his first trip there as crown prince, royal family member Lord Mountbatten abstained from attending the official state banquet. Mountbatten had been Supreme Allied Commander in the Southeast Pacific Theater and had lost men in battle against Japan. Queen Elizabeth, though, eased the tension, saying, “We cannot pretend that the relations between our two peoples have always been peaceful and friendly. However, it is precisely this experience which should make us all the more determined never to let it happen again.” The Queen maintained a close relationship with the imperial family, and needless to say, was warmly welcomed in Japan on her first visit as a state guest in 1975.

In 1998, in conjunction with a visit to Britain by Emperor Akihito, Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryūtarō wrote an article in the UK newspaper The Sun expressing his deep remorse and heartfelt apologies, and the British government decided to offer special benefits to former Japanese POWs. Former British Ambassador to Japan David Warren has indicated that the 1998 visit played an important role in that step toward reconciliation.

The strong bonds between Japan’s imperial family and the British royal family helped create a new relationship after the distrust born of war that still continues. Emperor Akihito visited Britain once more, in 2012, to celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation. Japan’s current emperor, Naruhito, also chose to study abroad in Britain while still prince. He researched the history of water transport on the Thames as a student at Oxford, where he lived in a student dormitory, drank beer at pubs, and lived a free student lifestyle. In 2015, Crown Prince Naruhito and Crown Princess Masako met with Prince William during his visit to Japan, and in 2018, their eldest daughter, Princess Aiko, attended summer school at Eton College. The royalty of Japan and Britain have shared almost familial bonds for three generations.

Their bonds have clearly played a role in reconciliation between both nations. Having a secondary diplomatic channel between two nations, apart from normal intergovernmental relations, has most assuredly been a significant part of the nations’ ongoing relationship.

2021 marks the 100th anniversary of Crown Prince Hirohito’s landing on the Isle of Wight. If the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, then the emperor and empress’s first international visit together will be to Britain. As Japan and Britain, island nations of the East and the West, build this new alliance, a new era of exchange between their royal houses will surely become a tie that binds them.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: From left, the Duke of Edinburgh, Elizabeth the Queen Mother, Empress Nagako, Emperor Hirohito, and Queen Elizabeth at a state banquet at Buckingham Palace, London, on October 5, 1971. © Jiji.)

imperial family Emperor Akihito Emperor Shōwa Anglo-Japanese Alliance