Tackling Japan’s Abandoned and Overgrown Bamboo

Society Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Examining Japan’s Bamboo Issues

Bamboo is everywhere in Japan. It beautifies Japanese gardens, features in fairytales, and is used to make everything from disposable chopsticks to traditional handcrafts. It adorns seasonal decorations as a symbol of growth and vitality, and its soft spring shoots are considered delicacies.

At the same time, the quick-growing plant has become a headache for rural communities due to growing tracts of abandoned bamboo stands, which are eyesores and wreak havoc on surrounding ecosystems. In the five years up to 2017, Japan added 5,300 hectares of bamboo forest to the 167,000 it already had in its forest area, much of it now overgrown. Below I look at what is driving this increase and examine possible solutions to the problem.

To grasp the severity of Japan’s growing bamboo troubles, it is important to understand the characteristics of the plant. Bamboo is part of the grass family. Most of the roughly 1,600 known species are found in tropical and temperate climates. Japan is home to around 100 species and is the northernmost extent of bamboo’s distribution. Large types, such as those from genus Phyllostachys common in Japan, are often misinterpreted as trees because of their height, but they are in fact closer in relation to rice and wheat than woody species like cedar or pine. Bamboos present many distinct characteristics that set them apart, of course, but for convenience’s sake it is easiest to consider them as giant types of grass. This impression is most notable when examining the flowers of the evergreen perennials, which exhibit very grass-like traits.

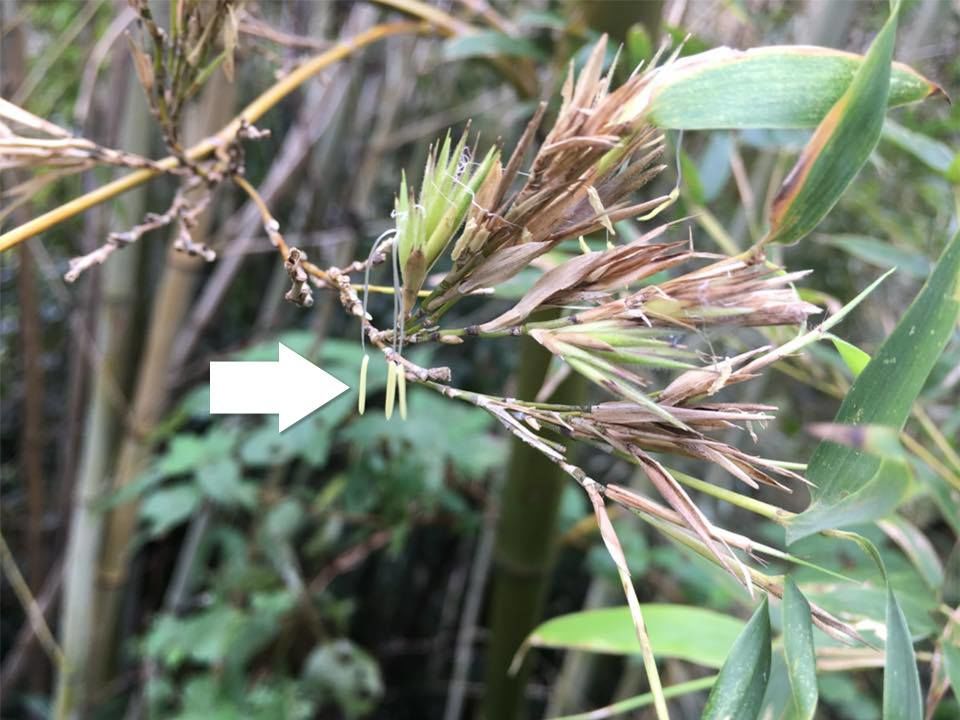

A blossoming hachiku, or henon bamboo, growing in Kyoto. The arrows in this and the following photo point to the anther at the tip of the stamen, the male reproductive part of the flower.

A mōsōchiku, or tortoise-shell bamboo, observed flowering in Kyoto.

Bamboo grows quickly and produces robust culms, traits that have long made it a valuable resource around the world. In Japan, it has traditionally been used to make common items like hand-held fans and broom handles, and also as a building material. Come spring, tender shoots, called takenoko, are dug up and eaten. It is naturally found in temperate through tropical climates around the world, and its utility has prompted people to plant it in new areas as well.

Shoots of hachiku poke out of the ground in a bamboo stand in Kyoto Prefecture.

Languid Bloomer

One of the few similarities giant bamboo shares with trees is its propensity to form large stands. However, tree-dominated forests perpetuate over long periods through the slow, cyclical process of plants growing from saplings to mature size, with competition for available sunlight helping control the population. Bamboo, on the other hand, spreads quickly, sending up shoots that reach full size in a single growing season lasting a few months, with the tall, leafy culms typically living between 5 and 20 years.

Although the towering culms are important, the heart of a giant bamboo forest is its nexus of rhizomes, a type of underground stem. Spanning out horizontally at depths typically down to 30 centimeters, the rhizomes, which are different than roots, support and connect the culms, store and convey nutrients, and produce new shoots (the takenoko that people find so scrumptious).

Rhizome systems of a mōsōchiku on display at the Kyoto Bamboo Park. Like culms, the subterranean stems are segmented.

Giant bamboo self-propagate primarily by rhizomes sending up new shoots. However, some species are known to flower and then wither in mass events that take place every century or so. Little is known about what drives this phenomenon, in large part because of the infrequency of events, although researchers are gradually identifying species of bamboo that exhibit the trait.

There is hope, however, that some questions will soon be answered. Japan is currently undergoing a mass flowering of henon bamboo, the first in some 120 years. The event is expected to last for the next 10 to 20 years, giving today’s scientists a once-in-a-lifetime experience to study the occurrence first-hand.

A stand of blossoming henon bamboo in Shiga Prefecture. The plants turn brown as they bloom.

Towering Troubles

Hachiku, mōsōchiku, and madake, also known as giant timber bamboo, are the main large species found in Japan. All three species are “running bamboos,” meaning their rhizomes extend out horizontally over long distances. They are hardy, and stands will thrive as long as growing conditions are favorable.

Japanese have cultivated the three species for ornamental purposes and to utilize the sturdy stems. Today, bamboo accounts for only a fraction of forested land in Japan, at less than 1%, although this ratio is gradually increasing as more stands are left to grow wild. Giant bamboo is rapidly spreading in wooded forests, as well as encroaching into agricultural land.

Mōsōchiku, whose stalks can grow to be over 20 meters in height, is the most common of the three giant species in Japan. It was brought over from China in the eighteenth century, and today is firmly established on all four of Japan’s main islands. It is the primary species cultivated for bamboo shoots. Verdant stands of mōsōchiku are also valued for their beauty, such as those in the Arashiyama area of Kyoto that draw tourists from around the globe.

For much of Japanese history, the demand for bamboo products, including takenoko and poles used in construction and for manufacturing, meant stands were well managed. However, as the country entered a period of rapid economic growth in the decades following World War II, reliance on domestic bamboo fell due to factors like the import of inexpensive edible shoots, the introduction of cheap and durable plastic products, and a transition to fossil fuels to meet energy needs. As a result, the hard work of managing stands of bamboo became economically unfeasible for many farmers, who abandoned plots in droves. Left unmanaged, the bamboo has since run wild, invading surrounding environments like farmland, meadows, and forests.

In the 1990s, researchers around the country began looking into the issue of abandoned giant bamboo forests. One of the most surprising discoveries was that when left unmanaged, stands expand their borders at the blistering pace of 1 to 3 meters a year.

A stand of mōsōchiku grows along the lower portion of a hillside in southern Kyoto Prefecture. The bamboo in early summer is distinguished from the surrounding forest by its yellowish-green foliage.

An abandoned riverside bamboo forest in southern Kyoto Prefecture.

Research is still underway on what happens when bamboo stands are left to grow wildly, expanding to replace surrounding ecosystems. There appear to be both positive and negative impacts from this growth, but on the negative side, the following can be listed. Most notable is the loss of plant diversity. New giant bamboo stems quickly grow to over 10 meters in height, soaking up all the available sunshine and making it impossible for slower-growing and smaller plants in the understory to survive. Unmanaged bamboo forests also provide shelter for animals like wild boar and deer, whose foraging can impact the health of surrounding woodlands as well as damage crops.

Abandoned bamboo forests are also an eyesore for local communities. Left uncleared, dead stalks and other biomass piles up, creating an unsightly tangle of withered and decaying poles. In such a sorry state, it is not unusual for a bamboo forest to attract unsavory behavior like the illegal dumping of trash, compounding the damage to the surrounding environment.

A wild boar finds food in a mixed tree and mōsōchiku forest area in southern Kyoto Prefecture.

A deer visits a mixed tree and mōsōchiku forest area in southern Kyoto Prefecture.

Recognizing the importance of mōsōchiku to industries like agriculture and its socially beneficial functions, the Japanese government has designated this Phyllostachys bamboo as one of 18 “industrially managed alien species,” meaning those with some value for industrial use that is not available in native species, but requiring careful attention to population management. Control measures are typically decided at the local level, such as how to deal with a bamboo plant encroaching onto a neighbor’s property.

Finding Solutions for Bamboo Woes

Efforts to deal with abandoned bamboo are largely regional in nature, with western Japan giving the issue the most attention. Over the last several decades NPOs, local governments, and private companies have poured time and resources into discovering new uses for bamboo to raise its value as a commodity.

The primary way of managing a bamboo forest is to clear fallen stalks to restore and maintain the landscape. Most projects also look to utilize bamboo as a sustainable local resource, with the lion’s share focusing on traditional uses like harvesting shoots and processing poles into raw materials for craft items. New, ambitious initiatives have also emerged to explore innovative applications, including turning dried poles into powder form or chips for use in the agriculture and livestock industries. A recent trend is for organizations to advertise their efforts in terms of forwarding global objectives like the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and decarbonization.

One initiative that has received media attention is a project involving organizations in eight prefectures to increase the production and consumption of domestically made menma. The popular condiment, much of which is imported, is made using bamboo shoots harvested at a height of around two meters, boiled, and pickled. Participating businesses and other groups meet regularly at so-called menma summits to share information.

Communities are also getting involved in addressing the issue of overgrown bamboo. A popular use for stalks collected from forests is carving or drilling patterns into tubes to create decorative lamps that are displayed at local gatherings or incorporated into installations by local artists.

A growing network of regional groups and facilities has also emerged, organizations like the Bamboo Innovation Group, Bamboo and Landscape Network, and Take Labo, which support research and hold seminars and other educational events. Together with national groups like the Japan Bamboo Foundation and Japan Bamboo Association, they are building on long-established expertise in managing forests to address the contemporary issues of unmanaged bamboo.

Treasure or Trouble?

Japan’s bamboo forests are a legacy of previous generations, and it is up to society today to decide whether to reduce their range as burdensome relics or to utilize the plants as valuable natural resources. There is no blanket answer, and each community will need to try different approaches to come up with a solution that fits its particular situation. What is certain, though, is that either path will require an understanding the biological properties of bamboo, a clear comprehension of local bamboo resources, and newly developed sustainable cultivation techniques and processing methods.

This year, 2022, is the year of the tiger. In Japan, the animal shares a deep association with bamboo, and the two are often depicted together, such as in pictures adorning seasonal greeting cards. This makes it an auspicious time to raise awareness of the problem of abandoned bamboo forests, which I hope motivates people to discover new, sustainable solutions.

(Originally published in Japanese. Translated, and edited in English by Nippon.com. Banner photo: Abandoned (left) and managed mōsōchiku bamboo forests in western Kyoto Prefecture. All photos © Kobayashi Keito.)