Tackling Omicron: Japanese Health Expert Warns of Risks from COVID-19 Strain

Society Health- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Cautious Optimism

MOCHIDA JŌJI The Omicron variant has spread quickly through Japan, but cases in Tokyo and other areas appear to be coming down. Do you think the country is past the peak of this wave, or is it too early to tell?

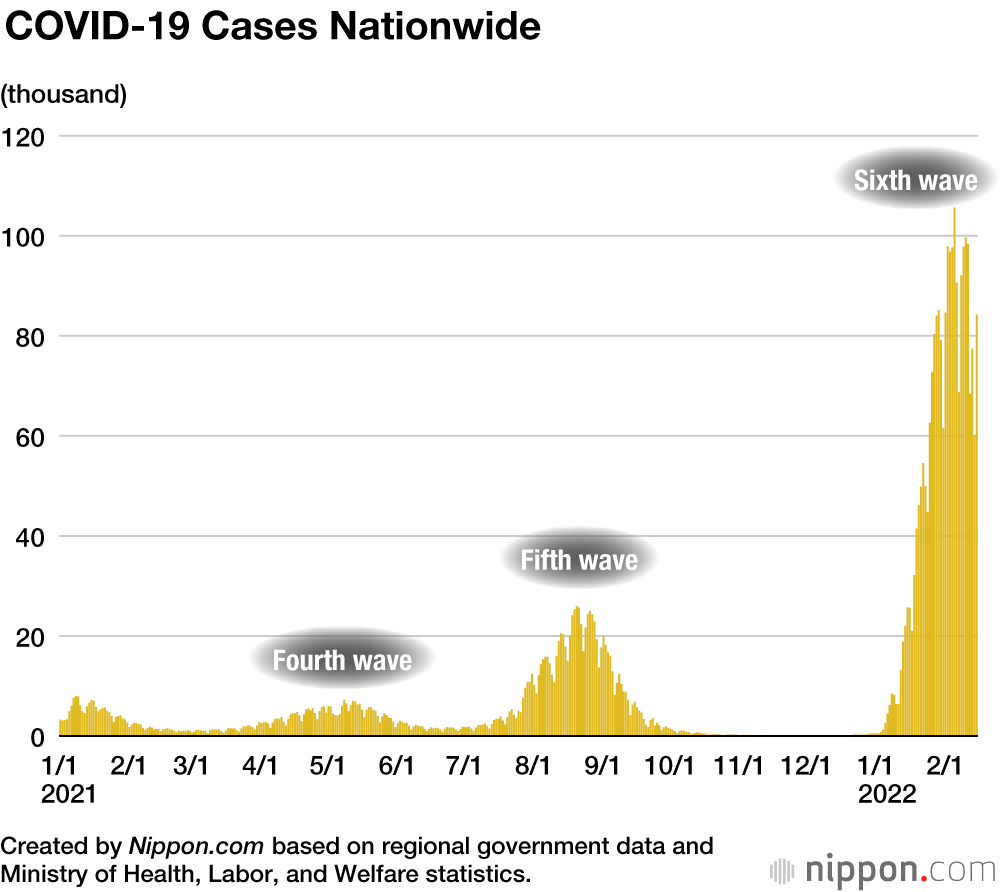

OKABE NOBUHIKO Evidence tentatively indicates that cases have peaked, but with the Omicron variant it’s hard to predict how the situation will unfold. Cases could drop dramatically, as with the fifth wave of the disease, or numbers may come down gradually. We have to keep in mind that because cases shot up so quickly, some regions haven’t had time to assess the full extent of infections, which leaves the possibility that figures could still be adjusted upward. I welcome the apparent fall in cases as a good sign, but a healthy amount of caution is still in order.

MOCHIDA The new BA.2 subvariant of Omicron that has popped up appears to spread more easily than its predecessor. Are we likely to see infections start ticking up again?

OKABE We’ve learned a lot about how the coronavirus behaves, which has allowed us to better anticipate the impact of things like the appearance of new strains. At the same time, though, the flood of information on COVID-19 can make people feel like they’re on a roller coaster. Rather than jump to conclusions one way or another based on the latest development, we need to continue keeping a close eye on the disease and be prepared for the next phase of outbreak.

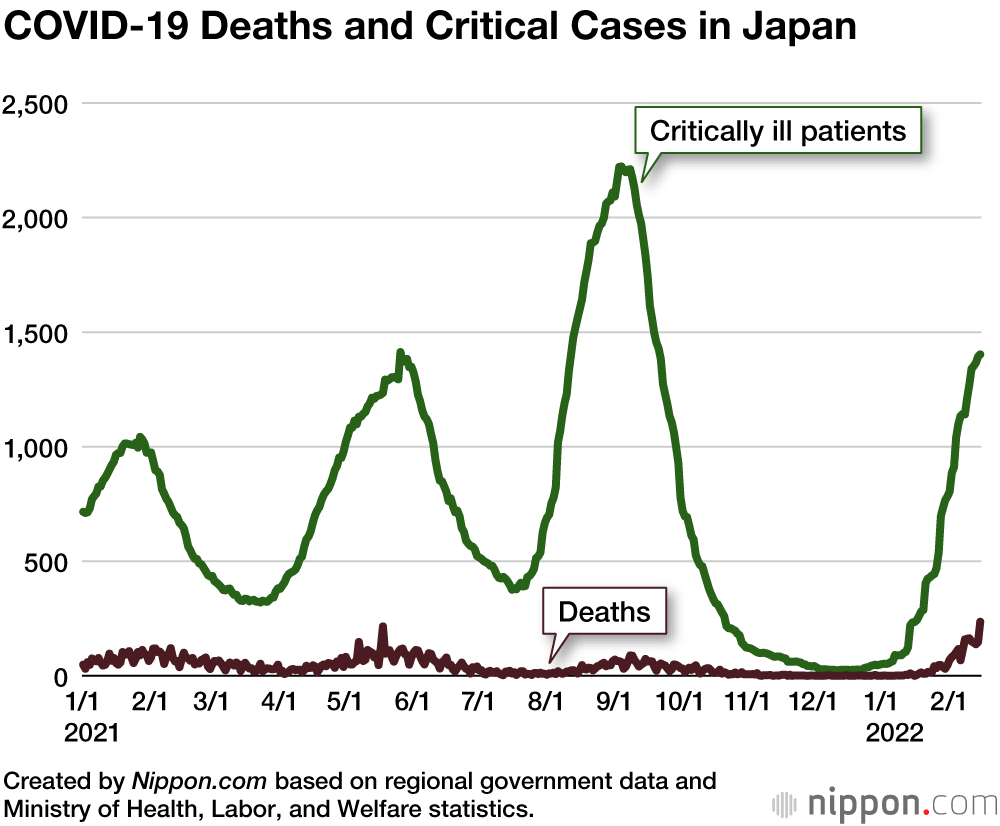

MOCHIDA Although cases are falling, deaths are continuing to rise to record levels, which some are blaming on the slow rollout of boosters to older residents.

OKABE When dealing with respiratory diseases like COVID-19, the elderly are always at greater risk of developing complications that can result in death. Knowing this, we need to use all the tools at our disposal to protect seniors, including vaccines, medicines, and preventative measures, as well as enlisting the help of caregivers and nursing home facilities. We can’t totally eliminate the risk of infection, though—only lower it. We need to accept that some people will not recover, and take steps to ensure they are as comfortable as possible as the disease runs its course.

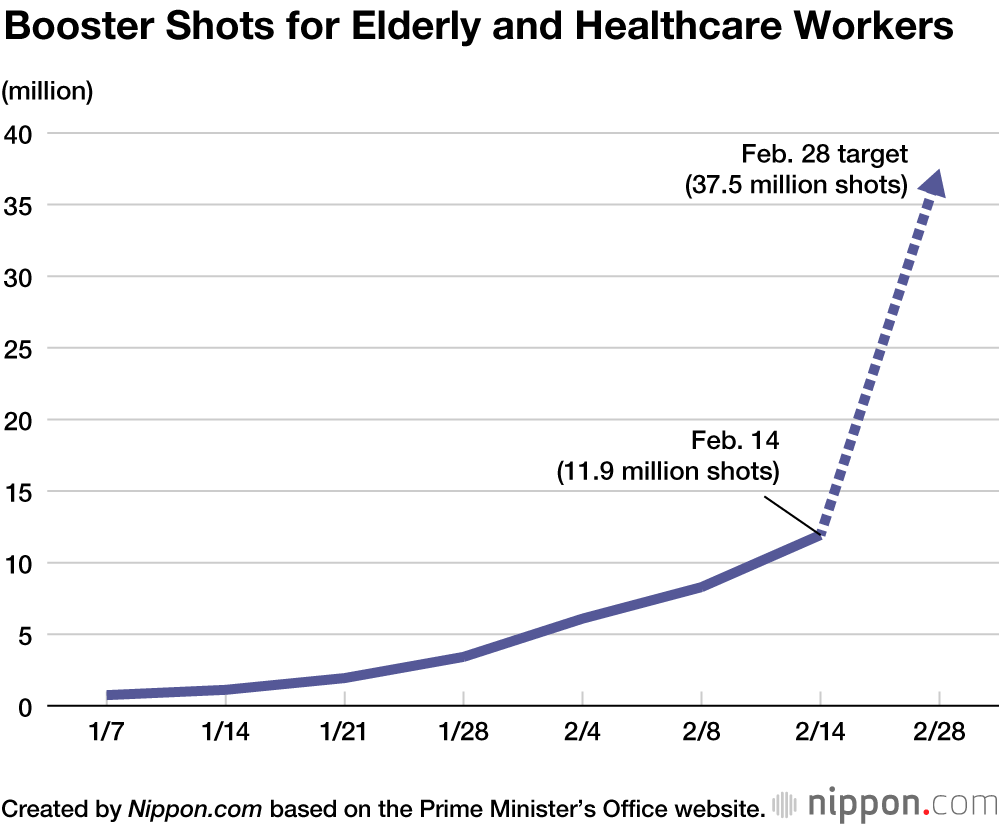

MOCHIDA Getting boosters to seniors as quickly as possible is crucial, but is the government’s goal of administering 37.5 million shots to healthcare workers and elderly residents by the end of February realistic, given the late start of the program?

OKABE Instead of spending time criticizing the government for setting such an ambitious goal, we need to focus our energy on hitting the target. Even if the effort falls short in the end, I think it would be unfair to label it a failure. Vaccines are an essential tool in the fight against the coronavirus, and the important thing is to get as many shots into arms as possible. The government has set its target based on the number of doses available and is hashing out the detail of the program with local authorities. I’m not up to speed on all the details, but I know that we need to work to improve the situation rather than stand around pointing fingers.

Care Facility Clusters

MOCHIDA What do you see as the best strategy for keeping seniors safe until more boosters are delivered?

OKABE If the rollout falls behind schedule, then we need to bolster non-pharmaceutical intervention measures that are already in place, including limiting close contact, social distancing, and sanitizing hands. Older people, unlike small children, are able to take precautions on their own to protect themselves, and should make every effort to do so. If individuals for whatever reason need assistance, staff at nursing facilities and caregivers need to provide the necessary support to guard against them getting sick.

MOCHIDA Clusters of COVID-19 infections have been an ongoing problem at nursing care facilities. Why is this, and what can be done about it?

OKABE One factor is that nursing homes are not medical facilities, and so COVID-19 strategies are typically not as robust as, say, at a hospital. This is in large part because outfitting a site with the necessary equipment and materials is challenging, both logistically and costwise. Many places just don’t have the resources available to do a thorough job. On top of this, a facility might have a full-time nursing staff, but not have a doctor on duty at all times, which is something that should be addressed. What needs to be done now, though, is to protect seniors by prioritizing boosters for both residents and staff members at nursing care facilities.

MOCHIDA How are the country’s medical services faring amid the surge of Omicron cases?

OKABE Medical workers are under a lot of pressure. January to March is a busy period for urgent-care facilities even in a normal year, and the coronavirus has only made things worse. There are more beds available compared to the fifth wave in August 2021, but these are starting to fill up as patients needing oxygen and even more serious cases rise. We are also seeing more seniors in need of elderly care getting infected, which puts an added burden on medical facilities.

Infections Among Young and Old

MOCHIDA Up to now, the infection rate among children has been relatively low. This has changed with Omicron, and we are now seeing a growing number of cases among teenagers and younger kids. Do we know why it’s spreading so fast?

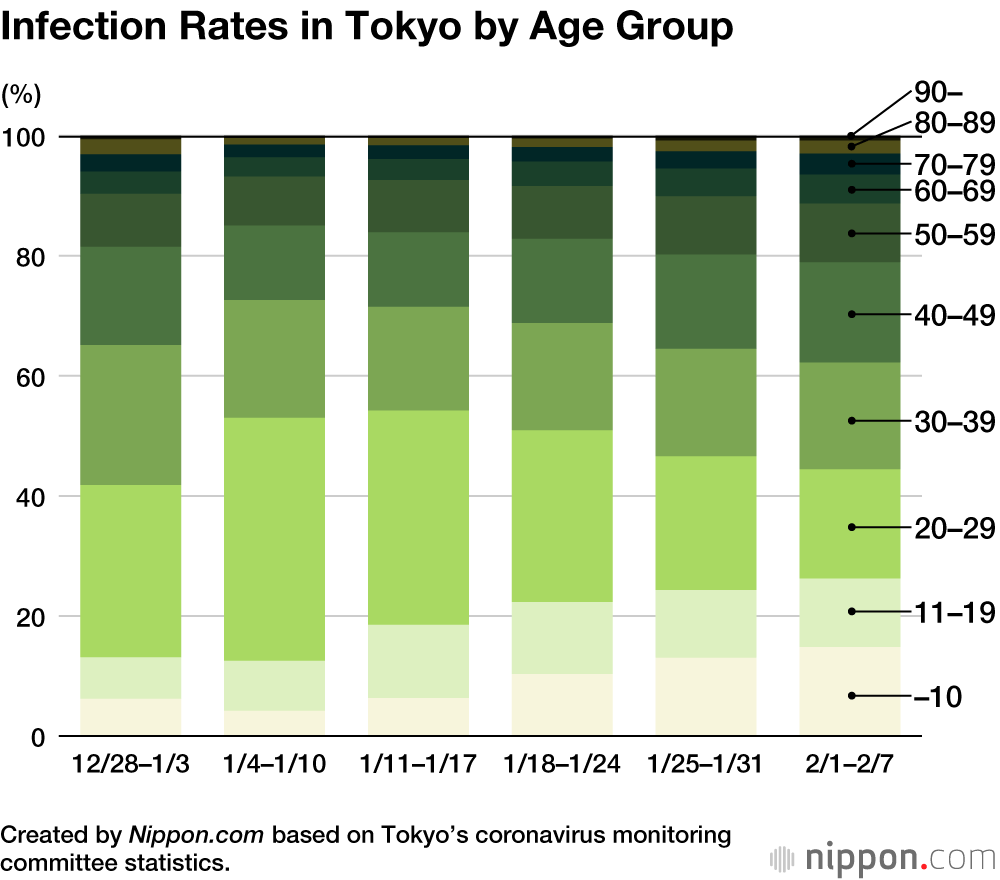

OKABE It’s too early to determine if children are more susceptible to the Omicron variant, or if other factors are at play. Up to now, people in their twenties and thirties made up a significant portion of infections, but cases among these age groups have come down due to factors like infected people developing immunity and increased vaccination rates. As a result, though, the focus of infections has shifted to more vulnerable populations—that is, children and the elderly.

This is to be expected for a number of reasons. First, the elderly have underlying diseases and weaker immune systems, and seniors who were vaccinated early on are starting to see the effectiveness of their inoculation fall. Then there is the fact that many children have yet to be fully vaccinated, or are not eligible to receive shots. Both groups spend time in close proximity to others at care facilities, daycares, or schools. Together, these factors make these groups more vulnerable to the virulent Omicron strain.

MOCHIDA If household transmission, particularly from child to parent, is part of what is driving the rapid rise in infections, can we expect to see a subsequent uptick in cases among the elderly as the virus circulates more widely through society?

OKABE That’s certainly a possibility, although currently infections among children don’t appear to be driving up cases more broadly. However, experts are divided on whether it would be a more effective strategy to confine children at home or to ramp up vaccinations. It comes down to two basic considerations: Do we decide that preventing infections is worth risking long-term, negative impacts on children by restricting their movements, such as halting in-person learning, or do we put the responsibility of curbing the spread of the virus on adult society? I feel that if we see cases skyrocket in the coming weeks that the former is a possibility. But as things stand now, I think the latter seems like the better strategy.

In choosing an approach, we also need to consider the knock-on effects on working parents from shutting schools and otherwise curtailing children’s movements. Droves of parents will be forced to stay home to look after their children, the vast majority of whom will not be infected with COVID-19. This will make it harder for employers in many industries to meet staffing requirements as employees take time off. Healthcare providers are already struggling to fill shifts, and we can expect the issue to spread to other sectors if we prioritize school closures.

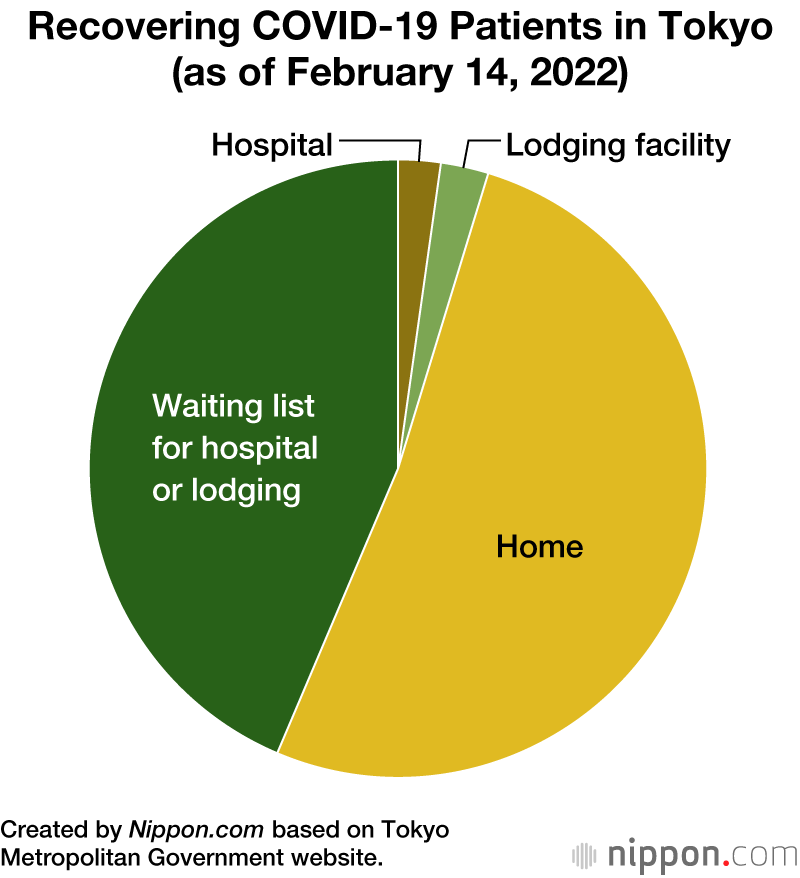

Rising Rate of Home Recovery

MOCHIDA There were a string of cases last summer of people dying while they were recuperating from infections at home. We are seeing this again with the Omicron variant. Are the systems that are in place to track the condition of patients as they recover working properly?

OKABE There’s nothing unusual about a patient with only mild symptoms recovering at home. It’s a standard practice with all sorts of diseases. It’s important, though, to ensure access to immediate medical attention, including hospitalization, if that individual’s condition suddenly worsens. We’re better prepared compared to the second and third waves, when hospital beds were in short supply. But there is still plenty of room for improvement. We need to bolster monitoring and other measures even more and stay on top of the situation.

MOCHIDA It seems that Japan is struggling to secure an adequate supply of COVID-19 drugs. Addressing this seems like an effective means for helping society return to normal.

OKABE Unlike specialized drugs for other infectious diseases and cancers, COVID-19 medicines are likely to be prescribed for a broad range of patients, even those with mild cases. This naturally means that we may see production failing to keep up with demand. We want to ensure that pharmaceutical manufacturers can make as many doses as possible, which means supporting them with public funds as needed. But even then it’ll be impossible to cover the entire population from the get-go. Since we can’t sit by waiting for a complete supply to be ready, we’ll need to distribute the drugs as they become available, and this means that some areas of need will arise that can’t be met right away. In order to make it through without requiring these new medicines, the best possible strategy is to avoid getting sick in the first place.

Timing of Boosters

MOCHIDA Japan has rolled out boosters at a slower pace than some other countries, in part due to authorities initially insisting on an eight-month timeline for delivering a third shot. Is there any truth to press reports that the period was shortened to six months in November due to input from the advisory committee on basic response policies for the coronavirus, where you serve as deputy chair?

OKABE I can’t recall the exact details of the November meeting, but I doubt there was much, if any, discussion on the booster timeline. Issues like procurement of doses, administration of shots, and the timeline of the booster program are decided by a Ministry of Health committee on vaccine policies, which is made up of vaccinology experts. The advisory panel for COVID-19 wasn’t in a position to decide on boosters, but was rather waiting on a final decision from the vaccine group.

Boosters were recommended from six months after the second dose, so the initial eight-month timeline was likely made for logistical reasons rather than based on medical considerations. Vaccine experts probably wanted to ensure there was plenty of time to prepare, including announcing vaccines, sending out vouchers, and arranging venues. Bumping everything up two months would have complicated planning for local authorities.

At that time, though, experts had yet to come to a clear consensus on the timing for boosters, and opinions were still shifting between six and eight months The focus instead was on finishing the second round of the initial vaccination program.

I wouldn’t say that the pandemic caught Japan flat footed, but I will say that the government, media, and society could do more to prep the country for another outbreak of an infectious disease. In the wake of the 2009 influenza H1N1 influenza pandemic, I argued for more spending to improve countermeasures and boost testing capabilities. Although some aspects of our response have progressed over the past decade, much more needs to be done.

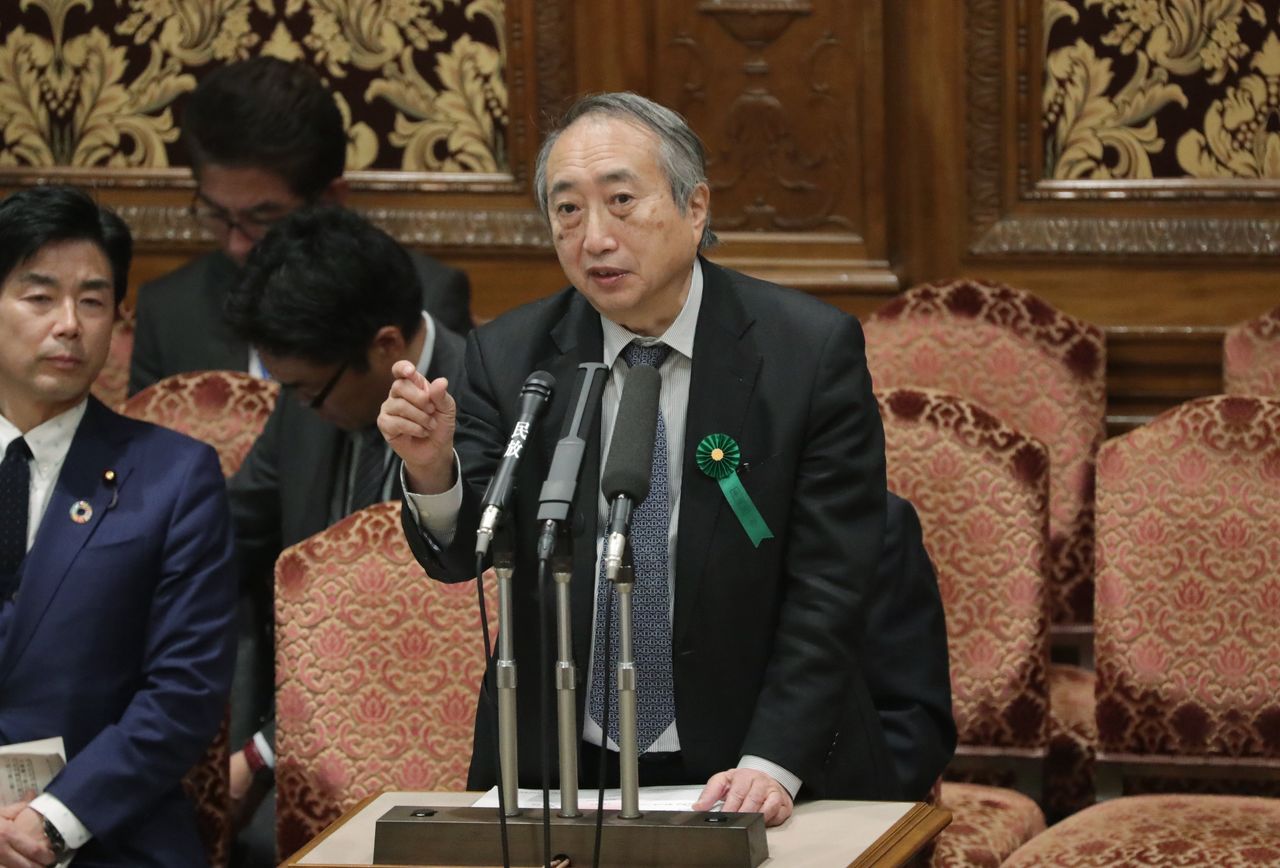

Okabe Nobuhiko answers questions during a House of Councillors budgetary committee meeting. (© Jiji)

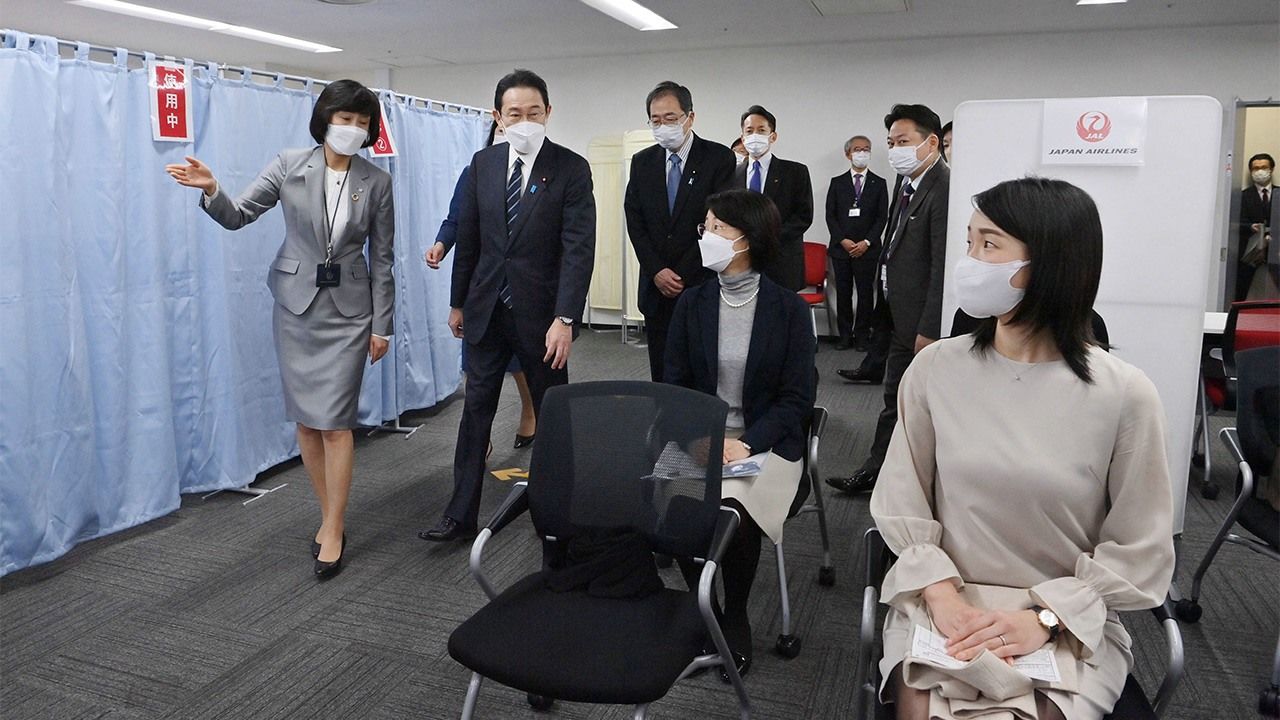

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, second from left, visits a vaccination center at Haneda Airport on February 12, 2022. © Jiji.)