Persistent Gender Gaps in the Japanese Labor Market

Economy Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Despite Legal Progress, a Long Way to Go

Since the Equal Employment Opportunity Law went into effect in 1986, related laws and systems have been developed and expanded to encourage women to enter the workplace and balance work and family life in Japan. The working environment for Japanese women has changed during this period.

According to School Basic Survey, the percentage of females who advanced to a four-year university after graduating high school was approximately 51% in 2020, up from about 13% in 1986. Similarly, in 2020 approximately 71% of women between the ages of 15 and 64 were employed, a major increase from the 53% in 1986. However, while “nonregular employees”—a category including part-time, registered, and other workers without full-time positions—made up approximately 32% of female employees in 1986, this percentage increased to approximately 56% in 2020 (Labor Force Survey). Furthermore, while about 70% of female workers returned to their jobs post birth of their first child in the late 2010s—after hovering around 40% for decades—there are large disparities between regular and nonregular employees (National Fertility Survey).

The Gender Gap report by the World Economic Forum in 2022 ranked Japan as 116 out of 146 countries, placing it at the bottom among the advanced economies. For example, in terms of labor force participation, pay for full-time workers, and the proportion of female managers, Japan—along with Korea—has one of the largest gender gaps among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development members.

Decreases in the labor force in Japan, as a result of the low birth rate and increasingly aging population, have made the effective use of women’s skills a major policy issue. Thus, the Act on Promotion of Women’s Participation and Advancement in the Workplace was passed in 2015. From the perspective of “utilization of female skills,” by improving their productivity and competitiveness, this legislation is highly important. However, I present challenges related to the utilization of Japanese women’s skills by focusing on what is referred to as “tasks,” or specific work carried out to complete a job.

Underemployed in High-Paying Positions

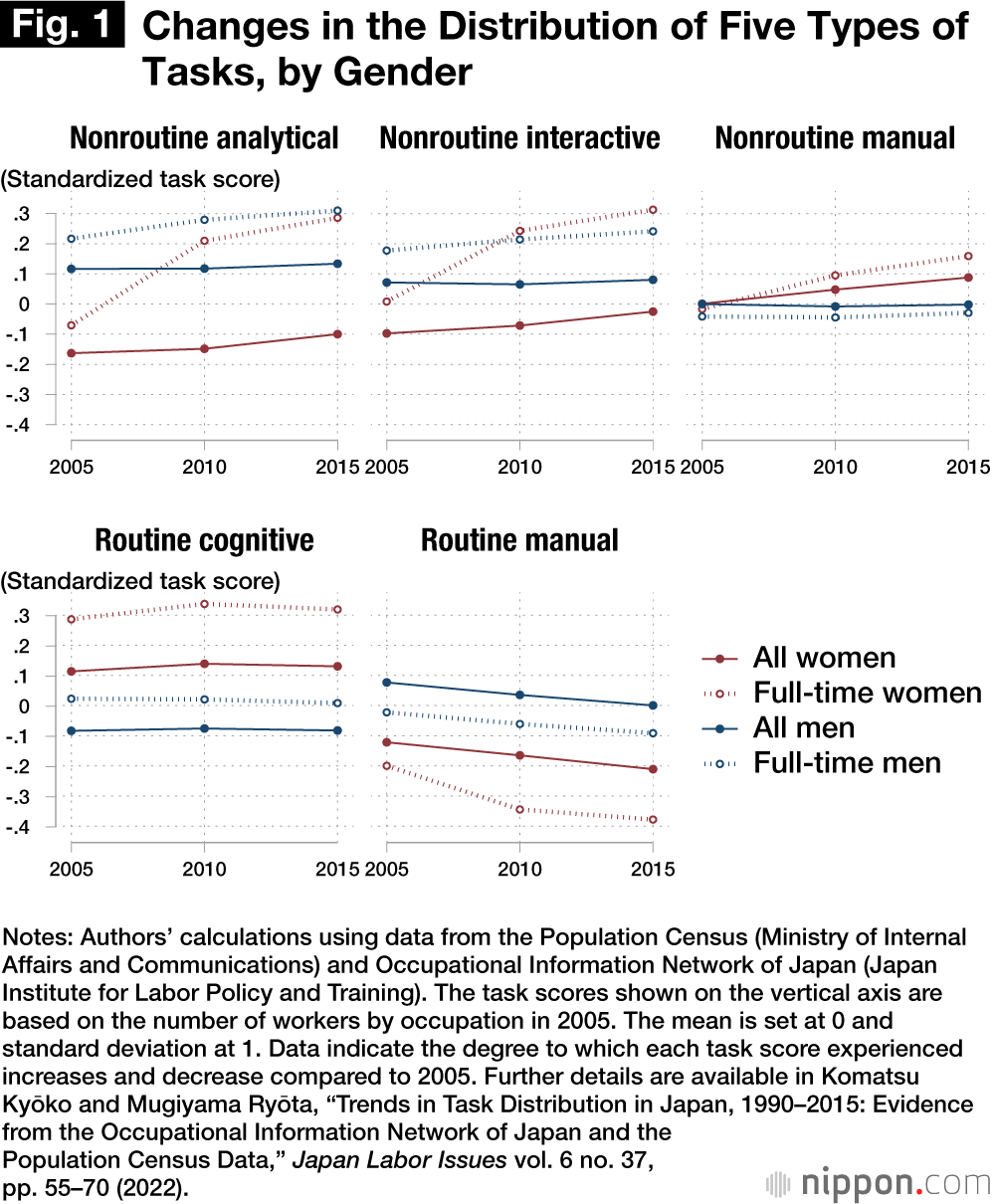

Figure 1 shows changes in the distribution of tasks for men and women in the Japanese labor market. Task scores were obtained by matching the occupations of the Population Census with occupations listed in the Occupational Information Network of Japan. Similar to O*NET in the United States, with this information, one can compare the skill levels and different tasks required for each occupation according to approximately 500 occupational categories.

If we look at the distributions for five types of tasks, we see that more men than women are engaged in “nonroutine analytical tasks” (e.g. research and design), which require high degrees of expertise, and “nonroutine interactive tasks” (e.g. management, consulting and education), which require highly advanced communication skills. On the other hand, more women than men are engaged in “nonroutine manual tasks” (e.g. services and hospitality), which require ability to deal with others flexibly but without high degrees of expertise. Even when focusing on routine tasks, we see that more women are engaged in intellectual “routine cognitive tasks” (e.g. clerical and accountancy work), while more men than women are engaged in physical “routine manual tasks” (e.g. manufacturing and agriculture). This indicates that fewer women are engaged in highly advanced, high-paying nonroutine tasks.

Next, we look at changes in the distribution of tasks since 2005. Women underwent significant changes compared to men, with notable shifts in the distribution of tasks assigned to female full-time employees, indicated by the red dotted lines. It shows that the share of female full-time employees engaged in routine manual tasks has decreased. Furthermore, there have been major increases in the share of women engaged in highly advanced, nonroutine analytical and interactive tasks. At the same time, the share of women engaged in low-skilled, nonroutine manual tasks (with lower wages) has also increased. While the shrinking gender gap for full-time, highly advanced nonroutine tasks is certainly welcome, overall the positive change is small. Although not shown in the figure, nonregular employees in general are not engaged in highly advanced, nonroutine tasks regardless of gender; and the difference between regular (full-time) and nonregular female employees has widened since 2005. This indicates that in recent years, the tasks performed by women have become more polarized.

Japanese Women: Skills Underutilized after Childbirth

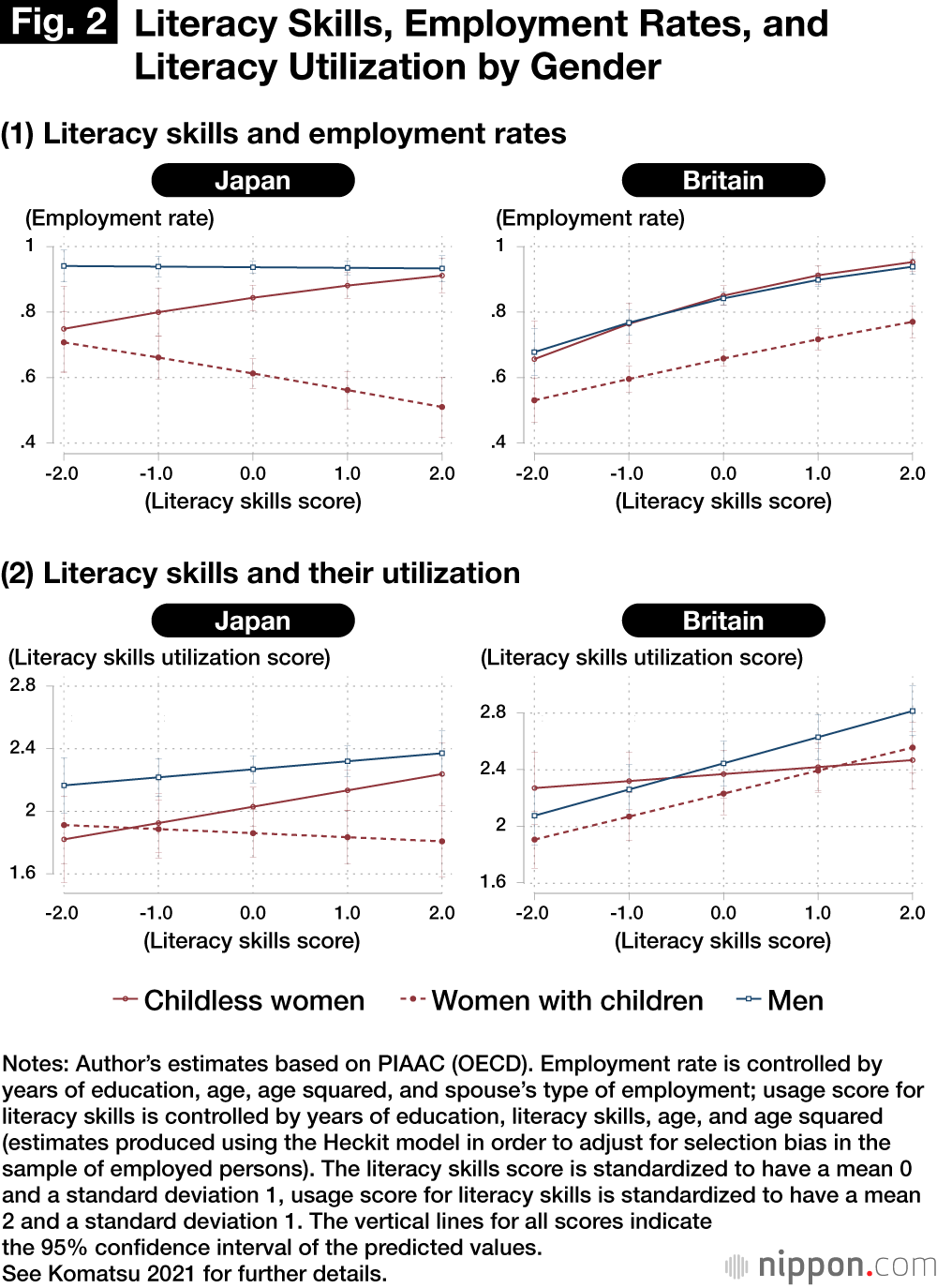

I will now compare gender differences in skill utilization between Japan and the UK, using data from the 2011 OECD Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies. PIAAC measures three types of skills (literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving using IT) and the frequency of these skill use at work in OECD member economies. Analysis revealed that there is greater gender equality in Britain compared to Japan. To explain, Figure 2 shows differences between men and women in terms of (1) literacy skills and employment rate and (2) literacy skills and skill usage (tasks). The sample includes men and women aged 25 to 44 as the child-rearing cohort at the time of the survey, which is when work-family balance support programs were being expanded in Japan. The data for women are divided into those with and without children.

In Japan, among childless women, employment rates increase with higher literacy skills, and those who are employed use their literacy skills to a greater extent as their skill level elevates. In contrast, women with children have lower employment rates as their literacy skills increase, with no tendency of higher use as their skill level elevates among those employed. In Britain, however, the employment rate for women with children improves as their skills increase, with higher skills being used to a greater extent among those employed.

These data suggest that, for women in Japan, having children is a major obstacle in taking up challenging jobs. Although not shown in the figure, full-time women and women in managerial and professional positions in Japan make better use of their literacy skills, and full-time women who are fully utilize their skills have a smaller wage gap with men. (For more details, see Komatsu Kyōko, “Nihon josei no sukiru katsuyō to danjo chingin kakusa: PIAAC o mochiita Nik-Kan-Ei-Noruuē hikaku” [Usage of Women’s Skills and Gender Wage Gaps: A Comparison of Japan, Korea, Britain, and Norway Using PIAAC Data], in Seikatsu shakai kagaku kenkyū [Journal of Social Sciences and Family Studies] 27, pp. 41–57, 2021).

Japan’s Unique Employment Practices

The above analysis indicate that, while the share of women employed in full-time jobs for nonroutine tasks is increasing, the under-utilization of highly skilled women with children and women in part-time positions remains a problem. While the gender gap for skill utilization is gradually shrinking, the divergence according to skill level between women with or without children is expanding.

Why is it difficult for highly skilled women with children to utilize their skills in the workplace, despite systems in place to support work and child rearing simultaneously? In addition to deep-rooted perceptions regarding gender roles as well as tax and social welfare systems that discourage women’s participation in the labor market, an often-cited factor is Japan’s unique employment practice. Full-time positions with the possibility of promotion in Japan entail no limit on the types of work or the number of work hours. Furthermore, these employees are expected to relocate whenever and wherever ordered by their superiors.

In this context, it is very difficult for women with housework and child-rearing responsibilities to meet the demands of such a position. Unlike in the United States and Europe, tasks and skills required for a job in Japan are not clear; therefore, once someone quits a job, it is difficult to find another full-time job of equal or higher level, where skills developed in the previous job can be utilized. As a result, when many women attempt to re-enter the workforce after leaving their jobs upon marriage or childbirth, they have little choice but to take on nonregular (part-time) jobs regardless of their skills.

As seen above, there are few opportunities for part-time employees to engage in highly advanced nonroutine task that fully utilizes their skills, and prospects for pay raises are low. Thus, as the share of women who take up these types of jobs are high, the gender pay gap in Japan remains a problem.

Better Working Conditions and Support for Skill Improvement

Simply creating programs designed to support better work-life balance is not enough to solve the problem regarding under-utilization of women’s skills. What is necessary is to change the assumption of companies that employees are supposed to work without any limit each day. They also need to make work responsibilities clearer to employees and move toward “telecommuting” (remote work) and other flexible styles of working. This implies making tasks and skills more visible and creating methods of assessing employees based on these criteria. Another important issue is abolishing differences in treatment of full-time and part-time employees.

To reduce the gender pay gap, it is not enough to simply encourage women’s labor participation. It is necessary to increase opportunities to shift or to be hired in full-time positions where training will be made available and skills utilized. This in turn requires the government to expand programs designed to assist women in re-entering the workforce. These programs need to include education and training and support for part-time employees who want to improve their skills.

According to the OECD’s 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment, Japanese high school girls had significantly lower occupational aspirations than boys. When asked what job they expected to have at the age of 30, Japanese girls were unique among developed countries in that “housewife” was in the top 10, as pointed out by gender specialist Miyamoto Kaori (2021, “‘Girls, be Ambitious!’: Why Japanese Girls have Lower Occupational Expectations than Boys,” Journal of Social Sciences and Family Studies (28): 1–22.) This may be related to the dearth of role models of women who hold positions of high socioeconomic status while being mothers at the same time. Thus, creating a society in which everyone can fully utilizing their skills in their desired jobs is an urgent task facing Japan.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)