Japan Needs a Unified Childcare Support System to Avert Demographic Disaster

Society Politics Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s falling birthrate is a silent crisis. The shrinking and aging of our population poses an immense threat not just to the social security system but to our society as a whole, as markets contract, the labor force shrinks, growth slows, regional economies decline, and communities unravel.

That said, whether or not to have children is the ultimate personal choice. It is a wholly private issue, inextricably tied to basic human rights. Family policies should be about creating the conditions that enable people to fulfill their individual hopes and removing the obstacles that stand in their way—not about setting numerical targets and pushing people to achieve them.

The challenge we face today is twofold: replacing the current patchwork of half-measures with a comprehensive, unified system and securing a stable, reliable source of funding to support continuous, consistent implementation over the medium and long term.

Basic Approach

A high-level government panel on social security reform recently called for greater emphasis on support for families with children and the younger generation as a crucial investment in the nation’s future and recommended a “unified, comprehensive childcare support system.”

There are two basic aspects to the design of such a system. The first is benefit design. This involves deciding what is to be provided to whom, which in this case means designing the programs needed to support childcare today. The second aspect is determining the funding model by which the system will be financed.

The funding model depends heavily on the benefit design. Of course, the reliability and ease of financing are considerations, but fundamentally, one needs a model that makes sense in light of the system’s basic purpose. In other words, we must start by identifying what the policy should offer and who will benefit.

Reconciling Work and Parenthood

In terms of benefit design, there are two important requirements.

The first is a focus on measures to make parenthood compatible with work. Simply lightening the economic burden of child-rearing is not enough. The government must provide broad-based support to ensure that all working-age people, regardless of gender, can work outside the home while having and raising children, if that is what they and their families desire.

After the birth of a child, one should be free to choose, without penalty, either to take time off from work and devote oneself to childcare or to place the child in outside care and continue working without interruption. Until we create such an “equal footing” society, it will be impossible for most Japanese women to work outside the home and contribute to society while simultaneously raising children. An essential objective of a comprehensive family-friendly policy should be ensuring that having children imposes no burden or disadvantage, whether one chooses to continue working or to take a hiatus from work.

In this sense, childcare leave and childcare services are two sides of the same coin. Currently, however, they are separate systems with entirely different financing mechanisms—the former supported by employer and employee contributions, the latter subsidized by the government (tax revenues). The government needs to combine these programs into one integrated system so that users can choose and access them seamlessly, according to their needs.

Needless to say, childcare leave should be available to all, and the level of pay should be commensurate with the parent’s previous level of income. Childcare services should also be a basic right, available to anyone who needs it, when they need it.

Meanwhile, steps must be taken to overhaul those provisions of the tax code and social security system that continue to discourage married women from entering the labor force, including the income tax exemption for dependent spouses and benefits for “category 3 insured persons” under the National Pension system.

Focus on Diversified Services

The second requirement for childcare support is a focus on diverse and flexible in-kind benefits, including daycare facilities and community childcare support centers, which offer consultation, after-school clubs, and other services.

While cash benefits can help support families financially, the top priority from the standpoint of income security should be on guaranteeing employment to the maximum degree possible and ensuring that working people can maintain their income while on childcare leave.

Childcare support must be designed to accommodate people’s diverse work styles and needs. We need to provide access not just to licensed daycare facilities but to a wide range of services, including home daycare and drop-in childcare centers. It should be stressed that working parents are not the only ones in need of such services. Support must also be available for employees on childcare leave and full-time homemakers, not to mention single parents.

In Japan, “solo parenting” by the mother is still the norm. But no one, employed or not, can raise a child all by themselves. It is vital that we offer a range of services, from community childcare support centers to short-term and drop-in daycare, to ensure that all families, all households, and all children have access to services that match their needs.

Sharing the Burden Equitably

Let us turn now to the matter of who should pay for these programs and how.

In the foregoing, I called for the integration of the childcare leave system, which is currently financed by employer and employee contributions, with childcare services, which are supported by public funding (taxes). I also urged that childcare benefits be provided primarily in kind, in the form of childcare services, and called for the creation of a unified system under which parents could directly access a wide range of childcare benefits. How should such a system be funded?

Supposing we proceed on the premise that the beneficiaries of a system should bear the burden. Of course, parents and families are the most obvious beneficiaries. But businesses would clearly benefit from such a system as well, as it would help them maintain a stable workforce and secure qualified personnel.

Ultimately, the Japanese economy as a whole benefits. When daycare is widely available, both parents are free to work outside the home. To appreciate the economic merits of such a situation, we need only look back to the time during the COVID-19 pandemic when daycare centers were closed. Many supermarkets and other businesses were hit by labor shortages that seriously impacted their operations.

Just as employer and employee contributions currently pay for childcare leave benefits, it makes perfect sense for employers to bear some of the costs of childcare services, which are the other side of the same coin. At the same time, since the proposed program is a kind of universal childcare support system to nurture the generation that will sustain Japanese society going forward, it is only natural that the costs should be distributed across society as a whole.

All of this leads logically to the conclusion that the main source of funding should be the consumption tax, which spreads the burden broadly and thinly across the entire nation. (The consumption tax is a specific-purpose tax dedicated to helping fund social security expenditures, and with the shift to a “social security system for all generations,” strategies to boost the birthrate have been included among expenditures for which consumption tax revenues may be allocated.) Overall, the basic funding model should probably center on national and local government outlays (financed primarily by the consumption tax), supplemented by contributions from corporations and from beneficiary families, along with others of working age, who will eventually be supported by the children that the system benefits.

Learning from France

France, which has the highest fertility rate of any country in the European Union, provides an example of a proactive, integrated family policy in which childcare support is financed by a combination of individual and corporate contributions.

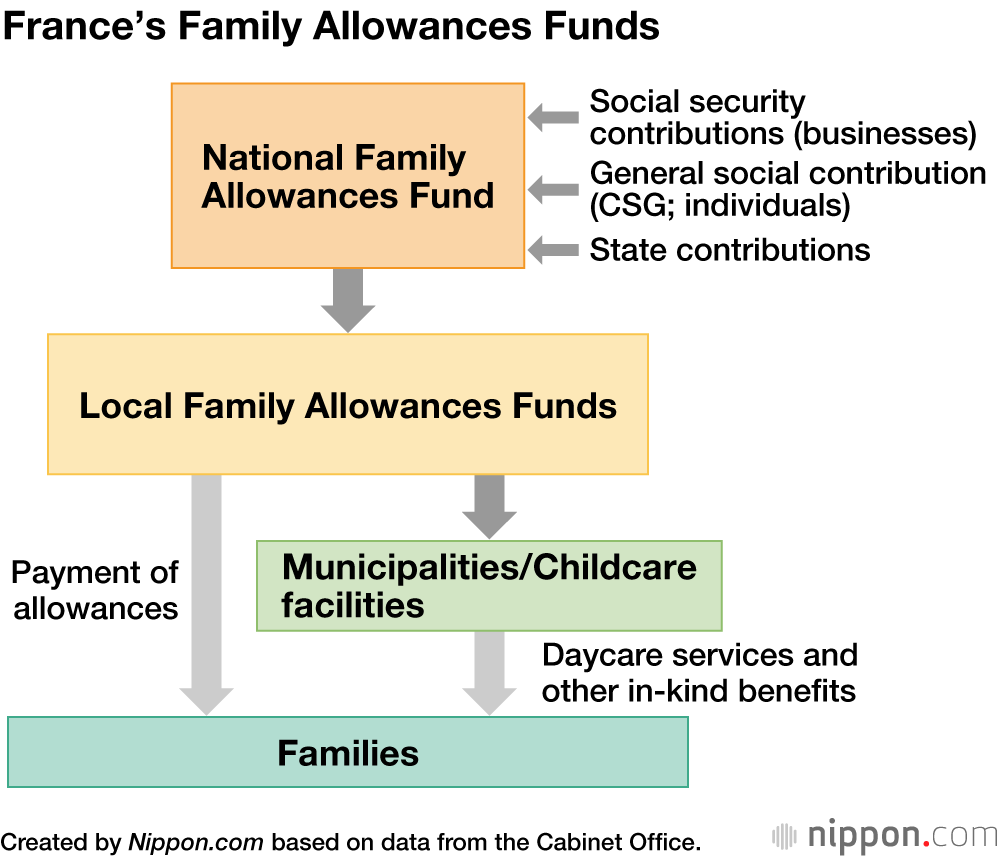

France currently spends about 3% of its gross national product on family policies, roughly twice what Japan currently spends on policies to address the declining birthrate. About 60% of that is covered by “social security contributions” from businesses. Another 20% or so is defrayed by the CSG, or general social contribution, a social security tax levied on personal income. Funding flows through the National Family Allowances Fund and a network of local funds to the local governments and childcare facilities that pay allowances or provide services directly to families. Each fund has a board of directors that includes representatives from business, organized labor, the self-employed, family associations, and other groups.

In the 1990s, policy makers in the Ministry of Health and Welfare (as it was then called) were eyeing the development of an integrated plan to boost the birthrate as the next major item on the social security agenda (after the adoption of long-term care insurance). There was serious discussion of an initiative to build a unified and comprehensive system of childcare benefits, combining expansion of the child allowance with such in-kind benefits as childcare services and drop-in daycare.

Three decades later, Japan has yet to come up with an effective response to its looming demographic crisis. The country’s population has been shrinking for the past 15 years. The time for deliberation has passed. Japan must take decisive action now, before it is too late.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo : Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, right, and Minister of State for Measures for Declining Birthrate Ogura Masanobu during a visit to Angel Land Fukui, a children’s museum in Fukui Prefecture, on March 2, 2023. © Jiji.)