Japan’s Incremental Immigration Reform: A Recipe for Failure

Society Economy Politics Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s immigration policy underwent a fundamental shift in 2019 with the establishment of the “specified skilled worker” program, says sociologist and migration expert Higuchi Naoto. By allowing non-Japanese with limited skills to secure work visas and creating a pathway to permanent residence, the Japanese government had officially opened the door to immigration on a broader scale. Yet it has steadfastly denied doing so. “The reason,” says Higuchi, “is fear of a backlash from the right wing of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party.”

The Forces Behind “Creeping” Liberalization

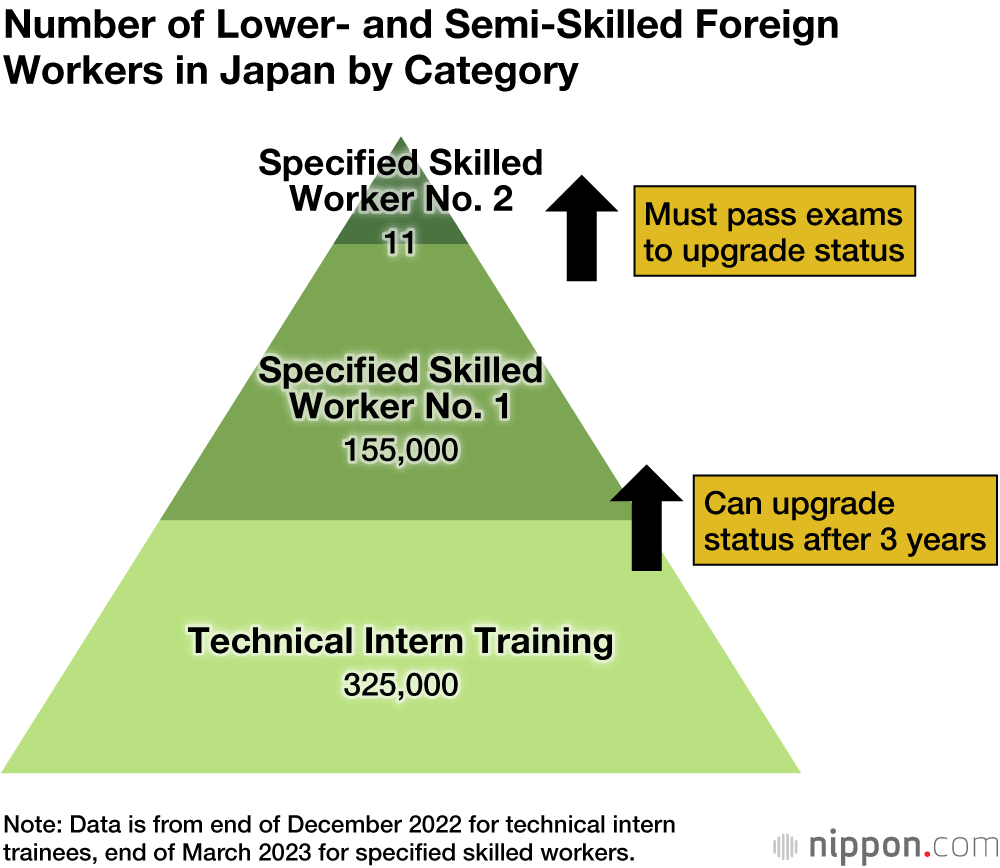

The Specified Skilled Worker No. 1 (SSW1) status of residence permits qualified foreign nationals (see table) to stay in Japan for a maximum of five years to work in any of 12 designated occupational fields, including construction, shipbuilding, and nursing care. Migrants classified as SSW1 are not allowed to bring their families to Japan. The SSW2 status of residence—reserved for SSW1 “graduates” with more advanced skills—can be renewed any number of times, and its holders may bring their families to Japan to live. SSW2 has been limited to workers in the construction and shipbuilding (including ship machinery) sectors, and only 11 workers had made the transition, according to the latest government figures. But on June 9 this year, the cabinet agreed to extend the scope of SSW2 to nine other occupational fields, including agriculture, hospitality, and manufacturing. (Excluded is nursing care, since carers can apply for long-term stays under a separate status of residence).

What precipitated the policy change?

Higuchi puts it simply. “The government was under pressure from business because the five-year permits of the [first wave of] SSW1 workers will expire next spring,” he explains.

Employers facing labor shortages are doubtless hopeful that some of their foreign employees will be able to stay on by upgrading from SSW1 to SSW2 status. To qualify, however, the workers will have to pass skills exams, currently under preparation by the relevant industry groups and government agencies.

“This is typical of the government’s incrementalist approach to immigration policy,” says Higuchi. “After putting an adjustable framework in place, it gradually expands the scope to create a fait accompli by stealth. Under pressure from various industries, it will doubtless continue to loosen restrictions bit by bit, by expanding the number of eligible occupations and reducing the difficulty of the exams, for example.”

Comparison of Specified Skilled Workers and Technical Interns

| Eligible employment fields/occupations | Eligibility, restrictions, period of stay |

|---|---|

| Specified Skilled Worker No. 2 | |

| 2 fields at present, to be expanded to 11 fields (excluding nursing care) |

|

| Specified Skilled Worker No. 1 | |

| 12 fields (14 occupations) |

|

| Technical Intern Training | |

| 87 occupations |

|

A System of Loopholes

Before 2019, Japan maintained a basic policy of granting work visas only to highly skilled foreign nationals. However, from 1990 on, the government established a number of exceptions and loopholes to facilitate the use of foreign labor in low-skilled jobs that were becoming difficult to fill. For example, after the revised Immigration Control Act came into force in 1990, third-generation descendants of Japanese émigrés (primarily from Brazil and other parts of Latin America) were able to settle in Japan as “long-term residents,” with no restrictions on employment.

Around the same time, Japan began accepting unskilled foreign “trainees” on a short-term basis. In 1993 this practice was systematized and expanded through the creation of the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP). Although the program’s ostensible purpose was to support international cooperation by transferring skills to workers from developing countries, it soon came under criticism as a government-sanctioned side door for foreign labor and a recipe for exploitation.

By the first decade of this century, Japan’s worsening demographic outlook bolstered the acceptance of lower-skilled foreign workers as full-scale employees, rather than so-called trainees. “The ruling party and the business lobby floated a number of reform proposals. One called for admission of 10 million foreign workers, another for the adoption of a three-year ‘temporary worker’ visa,” says Higuchi. “But none of them was adopted.”

Instead, the government gradually expanded the TITP, extending the period of stay from three to five years and including more and more industries and occupations in the program’s scope. The number of foreign “trainees” soared. (At last count, there were more than 320,000 foreign workers registered as technical interns, down slightly from the pre-pandemic level.) In anticipation of surging demand connected with preparations for the Tokyo Olympics, the government took action to increase the supply of construction workers by instituting a program under which foreign “interns” in that field could continue working in Japan for a few years after their internships ended. It also gave the green light for employment of non-Japanese agricultural workers in national strategic economic zones.

Through these incremental changes, says Higuchi, “the government laid the groundwork for adoption of the Specified Skilled Worker program, promoting [the acceptance of lower-skilled foreign workers] in practice even while publicly opposing it in principle.”

The TITP as Nursery

From the government’s viewpoint, says Higuchi, the much-vilified TITP probably qualifies as a policy success. “It’s provided labor for industries suffering from shortages without allowing the workers to settle in Japan. Sure, some trainees go missing each year, but only about three percent on average. From the government’s perspective, this means the program is being adequately managed.”

Critics inside and outside Japan, meanwhile, continue to slam the TITP, citing labor and human-rights abuses. In response, the government has begun talking about “progressively dissolving” the system as the SSW program gears up.

Higuchi doubts that the TITP will be dismantled anytime soon. “Foreign nationals who have worked as a technical intern for three years can transition to SSW1 without taking an exam. Otherwise, they need to [pass a test to] show Japanese competence at the N4 level [‘ability to understand basic Japanese’]. To secure workers with SSW1 status without relying on the TITP would involve a major expansion of Japanese-language instruction and testing programs in migrant-sending countries like Vietnam. A year of study is needed to reach N4, and prospective applicants would also need to prepare for the technical skills exam in their field of employment. Realistically speaking, the TITP mechanism for importing unskilled labor will be needed to secure an adequate number of legally employed workers [under the new program].”

Restricting Free Choice of Employment

The government has also said that it is considering loosening the TITP’s rule against changing jobs. But Higuchi is skeptical about the prospects for substantive reform. “Even if technical interns upgrade to SSW status, they’ll be required to find employment in the same industry,” says Higuchi.

The main concern among policy makers is that if foreign workers are free to choose their place of employment, they will gravitate to urban centers and industries offering relatively favorable working conditions. That would leave the employers and occupations most in need of foreign labor short-handed.

“Émigrés are by nature independent-minded people, and giving full play to that trait would ultimately benefit the economy as a whole,” says Higuchi. “But the current system is all about confining people to the categories they’ve been assigned. For example, it makes no provision for foreign nationals to operate their own businesses or work as independent contractors, even though a relatively high percentage of people in the construction industry are self-employed. The SSW program was adopted as part of a larger economic growth strategy, but as strategies go, it doesn’t make much sense.”

Lessons Not Learned

While Japanese bureaucrats may regard the TITP as a success, few would give high marks to the policy of granting long-term residence to foreigners of Japanese descent (Nikkeijin), says Higuchi. For one thing, a large number of the migrants returned home after losing their jobs during the Great Recession.

But the biggest problem, Higuchi says, is that the policy was not accompanied by adequate support and integration measures. “The majority [of South American Nikkeijin] remain stuck in temporary positions, even after thirty years working in Japan,” he notes. “Many of their children were never enrolled in school, and others stopped attending. It’s clear that the failure to actively integrate the [third-generation] Nikkeijin badly hobbled the fourth generation.”

“In the end, the policy can be viewed as a kind of experiment, testing what happens if the government allows immigration without doing anything for the immigrants. I’m sure the Nikkeijin would have achieved a lot more if they’d been provided with rigorous Japanese-language training when they first arrived in 1990. Yet I’ve seen no indication that policy makers have learned the lessons of that ‘experiment.’”

Or perhaps they have learned the wrong lessons. In 2018, the government established a new category of work visa for fourth-generation Nikkeijin, who were previously permitted to reside in Japan only as dependent family members. But the new work visas are much more restrictive than those granted the previous generation. Applicants must be able to demonstrate Japanese-language competence at the N5 level (“ability to understand some basic Japanese”), and they must secure sponsors in advance. Moreover, they are not allowed to bring family members, and their stay is limited to five years. Thanks to these restrictions, Higuchi says, “Practically no one has applied.” There are reports that the Ministry of Justice intends to grant long-term residence to such migrants after five years if they demonstrate N2 competence in Japanese (“ability to understand Japanese used in everyday situations, and in a variety of circumstances to a certain degree”), but there are no plans to loosen the initial visa and status-of-residence requirements.

A Patchwork of Policies

The creation of the SSW status of residence was a policy change spearheaded by the prime minister’s office, known as the Kantei. But the Kantei does not oversee or coordinate immigration control on an ongoing basis. “Big business is forever lobbying the Kantei on economic and labor policy, and in this case the Kantei yielded to industry’s call for deregulation,” says Higuchi.

In fact, there is no single “control tower” coordinating Japan’s immigration policy, which helps explain its lack of consistency and rationality.

“The Ministry of Justice, which has jurisdiction over immigration control [via the Immigration Services Agency], has considerable authority over the admission of foreign workers,” says Higuchi. “But it has no idea how those human resources should be allocated. The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare has a Foreign Workers’ Affairs Division, but it only has jurisdiction over building cleaning and nursing care. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries each propose separate quotas [for construction workers and agricultural/fisheries workers, respectively] on the basis of their own sectors’ needs. The reason the number of foreign construction workers has grown so rapidly is that the construction industry has very cozy ties with MLIT.”

What about the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, which oversees economic and industrial policy from a more sweeping perspective?

“It would certainly make sense for METI to take some initiative in the context of an overall economic growth strategy, but in fact it’s only shown itself interested in securing highly skilled personnel in the information and telecommunications fields.”

Another obstacle to a more comprehensive, rational reform of Japanese immigration policy is the fact that the Liberal Democratic Party has controlled the government for so long. Many countries have managed to develop a balanced policy as a result of the alternation of power between parties with different perspectives on immigration. But in Japan, regime change is rare.

“For the LDP government, at least, there’s nothing to be gained by abandoning the current incrementalist, patchwork approach. What it really wants to do is secure as much labor as possible without any abrupt increase, which would trigger a backlash from the party’s right wing. Imperceptible increases aren’t what Japan needs to avert serious labor shortages, but the government doesn’t seem overly alarmed.”

Can Japan Have Its Cake and Eat It, Too?

In Higuchi’s view, the Japanese government will have trouble meeting even its modest goals for expanding the labor force if it continues to cling to the principle that foreigners entering Japan for purposes of employment must come equipped with specific occupational skills. “From the standpoint of policy goals, it would make more sense to admit untrained workers and nurture their skills here than to use exams to screen out unskilled applicants,” Higuchi says.

At the same time, Higuchi stresses the need to lay a solid foundation for success by providing formal Japanese-language training and other systematic instruction to new arrivals.

“It’s not enough for local governments to offer Japanese classes once or twice a week. Newcomers need formal, intensive training at the outset to ensure that they can communicate in the workplace. And the Japanese government should guarantee their educational and living expenses during that period. Municipal governments can’t be expected to shoulder that burden. Yet the central government has done everything it can to sidestep investment in human resources and minimize its own expenses.

“In Europe over the past couple of decades, it’s become the norm to provide language instruction in conjunction with vocational training. For example, Germany provides expats with about 600 hours of language training [as part of its required integration course] and a monthly allowance of about 1,000 euros during the training period. The US government doesn’t make that sort of human investment—but then, neither does it require migrants to pass a skills test after a certain number of years.

“Japan, on the other hand, demands skills from its foreign workers yet refuses to invest in them. And this would be a smart investment, since it would help address our labor shortages and eventually yield returns in the form of tax revenues. The government really doesn’t get it. It wants to have its cake and eat it, too.”

Helping Migrants Realize Their Potential

Higuchi’s research on Nikkei immigrants in Japan has shown a strong correlation between Japanese-language proficiency and employment options.

“To move up to regular employment or start their own business, they need business-level Japanese. Also, they’re more likely to find good work with a recommendation from a Japanese acquaintance. Relying on networks of other immigrants mostly leads to low-paying temporary and contract work. Strengthening ties between migrants and the Japanese community fosters social integration and multicultural coexistence and delivers a whole range of economic benefits.”

Migrants tend to be resourceful entrepreneurs if given the opportunity. Even in Japan, South Asian expats managed to carve out a niche selling used cars and now do a booming business exporting used Japanese automobiles around the world. The most successful at this ethnic enterprise, says Higuchi, is a group of Pakistani expats who obtained legal residence status by marrying Japanese women.

“The OECD [Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development] has made the case that migrants contribute substantially to the local economy through their entrepreneurship and ethnic businesses,” says Higuchi. “But the Japanese government makes no provision for ethnic enterprise; in fact, it won’t even let foreign workers move into more promising occupations. That stifles economic dynamism and drastically limits migrants’ potential to contribute to growth. It’s time for a fundamental shift in thinking.”

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com. Banner photo: An Indonesian intern at work in a Japanese factory under the Technical Intern Training Program, Ōizumi, Gunma Prefecture, October 16, 2018. © AFP/Jiji.)

foreign workers immigration foreign labor Japanese language education immigrants labor shortage