Ikeda Daisaku and Kōmeitō: The Political Legacy of a Spiritual Icon

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Sōka Gakkai and Ikeda Daisaku

Sōka Gakkai was founded in 1930 by the educator Makiguchi Tsunesaburō as a lay society affiliated with the Nichiren Shōshū sect of Buddhism. Disbanded during World War II, it enjoyed rapid growth in the 1950s under its second president, Toda Jōsei, with a recruitment campaign focused on lower-income groups.

In 1960, after Toda’s death, Ikeda Daisaku took the helm at the young age of 32. Four years later, Ikeda founded the Sōka Gakkai’s political arm, the Kōmeitō (Clean Government Party). Under Ikeda’s charismatic leadership, Sōka Gakkai enjoyed an era of explosive growth, but its relationship with Nichiren Shōshū soured. In 1979, Ikeda was obliged to renounce the presidency, though he retained de facto control as honorary president. In 1990, Sōka Gakkai and Nichiren Shōshū went their separate ways.

As relations with the parent sect grew strained, Ikeda continued to draw followers to Sōka Gakkai by augmenting his own authority and prestige as a religious leader and spreading the faith overseas.

Ikeda’s spiritual authority grew as he developed and disseminated his own interpretation of Nichiren Buddhism, propagating a belief system that might be termed Ikeda-ism. Meanwhile, his prestige benefited from the personal ties he developed with political leaders at home and abroad. His circle of acquaintances included current and past Japanese prime ministers (Ikeda Hayato, Satō Eisaku, Fukuda Takeo) as well as such global figures as Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, and South African President Nelson Mandela.

Relations between Japan and China were of particular importance to Ikeda. Speaking at a Sōka Gakkai students’ meeting in September 1968, at the height of the Cold War, he issued a bold proposal for normalization of diplomatic ties between Japan and the People’s Republic of China. Sōka Gakkai credits Ikeda with paving the way for the 1972 agreement that established diplomatic relations between Tokyo and Beijing, ranking that among his greatest achievements.

Ikeda’s pro-Chinese sentiments were reflected in the policies of Kōmeitō. In the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Incident, when the Chinese government was under harsh global criticism for its violent suppression of the student democracy movement, Japan became the first member of the Group of Seven to restore high-level relations with Beijing, partly in response to Kōmeitō’s vigorous lobbying.

In 1975, Ikeda established Sōka Gakkai International as a global umbrella organization, with himself as president. He retained his position at the top of SGI even after stepping down as president of Sōka Gakkai (Japan) in 1979. With a following spanning 192 countries, Ikeda Daisaku’s fame spread all over the globe.

Today, Sōka Gakkai boasts a membership of more than 8 million households in Japan and some 2.8 million members overseas.

Plunging into Politics

In 1964, just four years after taking the helm of Sōka Gakkai, Ikeda plunged head-first into national politics with the formation of Kōmeitō (Clean Government Party).

This was a time when party politics in Japan was sharply polarized, with the continuously ruling Liberal Democratic Party on the right, supported by big business, and the opposition Socialist Party of Japan on the left, sustained by organized labor. This left a large swath of lower-income working people—including small shopkeepers and employees of local businesses—without a voice in government. Ikeda decided to target this group and bring it into the fold. Accordingly, the newly formed Kōmeitō took a populist tack, promoting social welfare programs aimed at enhancing the economic security of the “common folk.”

Another central tenet of Kōmeitō was pacifism, a principle embraced by Sōka Gakkai since its inception. Back in the 1940s, the militarist Japanese government had cracked down hard on the dissident, pacifist Sōka Gakkai; Makiguchi, its first president, had refused to recant and had died in prison. Given this history, it was natural for the political arm of the Sōka Gakkai to position itself as the party of peace and a determined opponent of the conservative LDP, which favored revision of Japan’s war-renouncing Constitution.

Crisis and Metamorphosis

After the launch of Kōmeitō, the biggest political decision of Ikeda’s career probably came in 1999, when the LDP approached Kōmeitō for coalition talks.

For the first three decades of its existence, Kōmeitō remained at heart an anti-government party, even while cooperating with the LDP on specific policy issues. In 1993, when the LDP lost its lower house majority, Kōmeitō joined an anti-LDP coalition headed by Prime Minister Hosokawa Morihiro. This was a natural development, consistent with the positions the party had upheld since its formation.

But new challenges emerged after the LDP returned to power in an unlikely coalition with the JSP. Around this time, Kōmeitō and Sōka Gakkai came under concerted attack in the Diet, accused of violating the separation of religion and the state required by article 20 of the Constitution. There were repeated calls to bring Ikeda up before the Diet to testify in connection with proposed amendments to the Religious Corporations Act. Although Ikeda was able to avoid questioning in the Diet, the threat of a sustained government-backed assault, with Ikeda himself as a prime target, was deeply alarming to Kōmeitō and Sōka Gakkai.

In 1998, the LDP suffered a major electoral setback in the House of Councillors. Although the party retained control of the House of Representatives and the government, newly appointed Prime Minister Obuchi Keizō knew he would need to enlist the cooperation of smaller parties to get key legislation through the upper house, and he set about building a coalition with the (conservative) Liberal Party and Kōmeitō. After policy discussions with the two other parties, Kōmeitō agreed to join the coalition in the interests of “political stability.” There can be no doubt that the final decision was Ikeda’s.

It was an astonishing about-face for Kōmeitō, which had been attacking the LDP’s policies right up to the moment it was approached to join a coalition.

The Era of Compromise

In the end, Ikeda proved himself a pragmatist. With Sōka Gakkai itself under attack, he prioritized the organization’s defense over adherence to the ideological principles Kōmeitō had espoused since its founding.

Kōmeitō has remained the LDP’s junior coalition partner ever since, apart from the three years (2009–12), when the Democratic Party of Japan governed. Nowadays, the LDP has the Diet majority it needs to pass legislation on its own, but it owes that majority in large part to electoral cooperation with its coalition partner. In many cases, it is only the endorsement of Kōmeitō—with its dedicated, well-organized base—that enables LDP candidates to defeat their opponents in the lower house’s winner-take-all single-member districts.

As the junior member of the ruling coalition, Kōmeitō has had little choice but to adopt a more realistic line on foreign policy and defense. In 2003, under Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō, Kōmeitō worked with the LDP to enact ad hoc legislation allowing the deployment of Self-Defense Forces to Iraq during wartime. Under the second administration of Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, Kōmeitō approved the cabinet’s reinterpretation of the Constitution to allow limited participation in collective self-defense, and it fought hard for the passage of controversial security legislation incorporating this key change. At the end of 2022, in another historic shift, the cabinet approved a new national defense strategy predicated on possession of a “counterstrike capability” (the ability to strike enemy missile bases preemptively), and Kōmeitō accepted this as well. Given these compromises, it has become difficult for Kōmeitō to present itself as the party of peace.

Life after Ikeda

After 2010, Ikeda withdrew from public life, leaving the organization’s day-to-day affairs in the hands of an executive board headed by Harada Minoru, the sixth president. But even in his later years, he remained the symbolic head of the organization and a towering spiritual leader with the power to steer Kōmeitō and thereby influence national policy. His death is bound to affect the relationship between Kōmeitō and its base and the party’s policies, however subtly.

There have already been strong indications that Kōmeitō’s vote-getting machine is losing steam. One reason is simply that election campaigns are a growing burden on Sōka Gakkai’s aging members.

The members of Sōka Gakkai consider themselves disciples of Ikeda Daisaku. Devotion to their spiritual leader has motivated them to organize, rally, and solicit votes on behalf of endorsed candidates (whether they be Kōmeitō or LDP politicians). In Ikeda’s absence, motivation is sure to flag. That will be the situation heading into the next elections for the House of Representatives and House of Councillors. A continued decline in Kōmeitō’s turnout and vote tally is bound to weaken the party’s position within the ruling coalition.

Internal dissatisfaction with the policy compromises and electoral cooperation imposed by the LDP-Kōmeitō coalition could also take its toll. For 24 years, Sōka Gakkai members were loath to question Ikeda’s judgment on the issue, but now that he is out of the picture, there will be more room for debate regarding the pros and cons of the arrangement. Over the long run, the organization could begin to pull back from politics.

As noted above, Kōmeitō has compromised repeatedly on foreign policy and security issues since forging an alliance with the LDP. Whether this trend continues will hinge on the judgment of President Harada and the executive board. If they place top priority on preserving the coalition, Kōmeitō will continue to let realism dictate its foreign and defense policies. If the movement’s leaders decide it is time to reaffirm the party’s founding principles, Kōmeitō will have to take a more independent stance on diplomacy and security policy.

What is unlikely to change is the basic focus of Kōmeitō’s domestic policies. Throughout the coalition era, it has continued to champion measures to lighten the economic burden on lower-income households and assist society’s vulnerable members. This focus is de rigueur, since the party’s election results depend entirely on the voting behavior of the Sōka Gakkai community, which consists largely of lower-income households. Ikeda’s death has done nothing to alter this fundamental relationship. On pocketbook issues, Kōmeitō must continue to cater to its base.

Questions about Religion in Politics

While Sōka Gakkai is by no means the only religious group in Japan that endorses specific candidates in public elections, it is the only one with its own dedicated political party—even if it officially separated from Kōmeitō in 1970. Moreover, the Diet has had few opportunities to debate the issue of separation of religion and state since Kōmeitō entered into a ruling coalition with the LDP.

Furthermore, since the second administration of Prime Minister Abe Shinzō (following Ikeda’s withdrawal from the public eye), there have been reports of direct policy consultations between senior government officials and the Sōka Gakkai leadership. The opposition has seized on this as evidence of a de facto “LDP-Gakkai coalition.”

Ultimately, it was Ikeda Daisaku’s leadership that ignited and fueled the controversy by powering Sōka Gakkai’s phenomenal growth as a religious movement, founding a political party to represent that movement, and approving the LDP-Kōmeitō coalition. In other words, the persistent constitutional and ethical issues raised by Kōmeitō and its role in the government are the product of the Ikeda era. It will be up to his successors to resolve those issues.

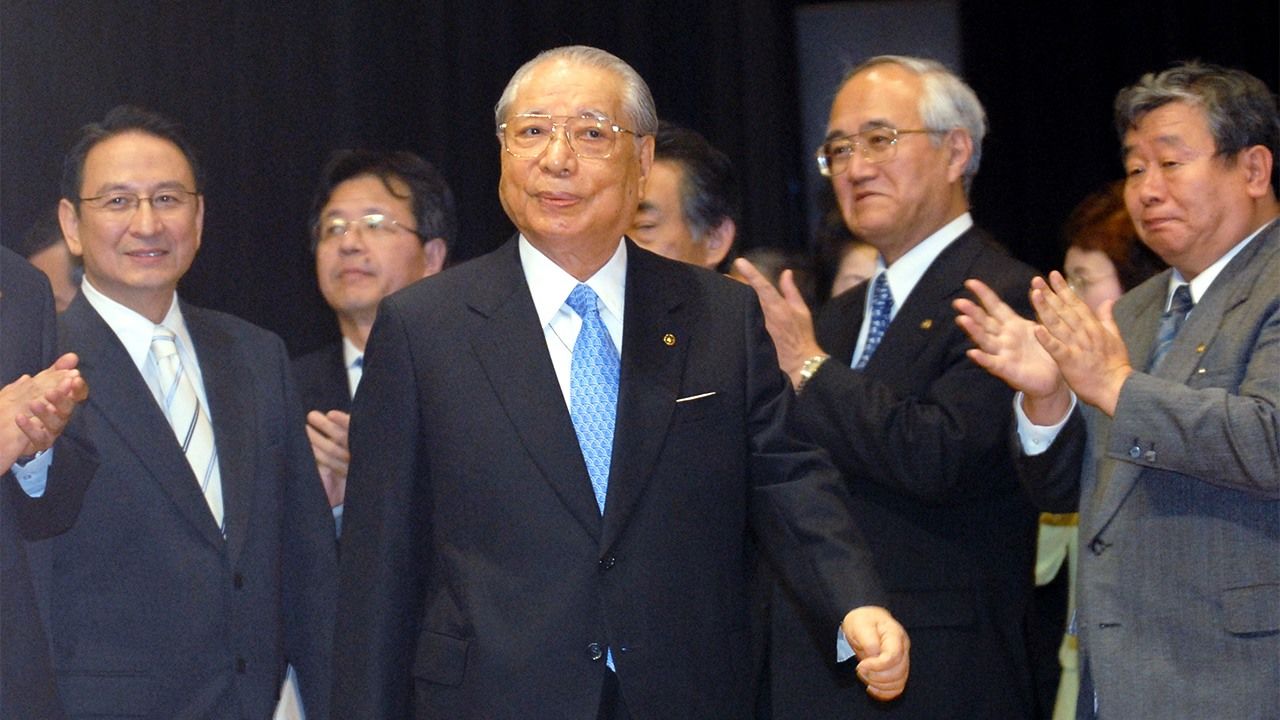

(Originally published in Japanese on December 26, 2023. Banner photo: Ikeda Daisaku of Sōka Gakkai receives an honorary professorship from Beijing Normal University at Sōka University in Hachiōji, Tokyo, on October 7, 2006. © Jiji.)