A Century at Kōshien: Japan’s Iconic Stadium Still Going Strong

Sports Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Early Sporting Legacy

At 100 years of age, Kōshien Stadium in Hyōgo Prefecture’s Nishinomiya stands as a monument to Japan’s undying love of baseball. The secret to the iconic ballpark’s longevity is its ability to change with the times while remaining true to its heritage. After a century of hosting games, it offers a sustainable model that contrasts with Japan’s raze-and-rebuild approach to sports venues.

The roots of Kōshien are deeply entwined with the nation’s prestigious national high school baseball championships. The inaugural tournament took place in Osaka in 1915—well before even the launch of the country’s pro league. The event moved to a larger ballpark operated by Hanshin Electric Railway (Hankyū) for its third installment, but the popularity of the competition quickly outstripped the venue’s capacity to host it. In response, the main sponsor, the Osaka-based Asahi Shimbun, approached Hankyū about building a new, larger stadium.

Misaki Seizō, Hankyū’s managing director, wanted a venue that would rival the world-famous Yankee Stadium. To this end, he ordered a section manager from the company who was in the United States to procure plans for American sporting facilities. Misaki put his young employee Noda Seizō in charge of designing the new stadium. As Yankee Stadium was being rebuilt, Noda based his design on the Polo Grounds, the home of the New York Giants (now the San Francisco Giants). Ground was broken on March 11, 1924, and the project proceeded at breakneck speed, with the grand opening taking place a mere four months later, on August 1.

The stadium has an unusual name. In deciding it, the set cycle of 10 calendar signs (jikkan) and 12 zodiac signs (jūnishi or eto) were used. In 1924 there was a highly auspicious grouping of 甲 (kinoe) and 子 (ne), the “wood-rat” combination that comes about just once every 60 years. To the end of these was added the kanji character 園 (en), meaning park, and the Japanese pronunciation of the characters produced the now widely recognized name Kōshien.

Although primarily a baseball venue, Kōshien was billed as a multipurpose stadium. Over the years it has hosted sports competitions ranging from athletics to soccer to rugby, not to mention a ski jumping tournament. At one point, there was even a gymnasium and heated pool housed beneath the outfield stands. This multisport legacy lives on in the form of the Kōshien Bowl, the American football college championship held each December.

Restoring a Kōshien Symbol

Among the stadium’s many trademarks is its thick outer covering of ivy. The plants, today numbering 430 in all, were originally planted in the winter of 1924 to brighten the beak, concrete exterior. Over the decades, the ivy thrived, covering vast expanses of the ballpark’s exterior and even becoming home to snakes and other wildlife. When the stadium closed for renovation in 2007, a massive project that lasted until 2010, the ivy had to be removed so that work could continue.

Its restoration was a top priority, though. A call went out to the thousands of schools that had received cuttings of Kōshien ivy to mark the last summer high school baseball championship of the century in 2000. Several hundred schools donated plants in top condition from their own growths, and more were propagated from seeds collected from around the stadium. The hardiest of these plants were selected for planting.

Members of the baseball team at Hashimoto High School in Wakayama Prefecture tend ivy from Kōshien, in a photo taken on July 6, 2006. (© Kyōdō)

The project was a success, with the last transplantation taking place in March 2009. Since then, the ivy has gradually reclaimed its place on the outer wall, returning the ballpark to its former appearance.

Sacred Soil

Another enduring symbol of Kōshien is its dark-hued, all-dirt infield. The stadium was built atop the alluvial deposits of the Saru River, a tributary of the important Muko River, and was once acclaimed for its picturesque white sands and rows of pines. However, the lightly tinted native soil proved unsuitable—it was thought that the glare produced by the summer sun would mask the movement of the ball. The first infield instead was comprised of a combination of red-clay soil from Awaji Island and black soil from Kumochi and Kobe, Hyōgo Prefecture.

Sources for Kōshien’s iconic black soil have varied over the decades, with dirt from places including Tsuyama in Okayama Prefecture, Suzuka in Mie Prefecture, and Kanoya in Kagoshima Prefecture being used. Sand, an important ingredient in the mix, has been sourced from a local beach, Kōshien-hama, as well as from Jōyō in Kyoto Prefecture and even China’s Fujian Province. The blend is not consistent, but is varied by season and environmental conditions, with the ratio of sand increased in spring in expectation of the frequent seasonal rains, and more dark soil used in summer to make the ball easier to see on the sunlit surface.

It is tradition during the spring and summer high school tournaments for losing teams to collect souvenirs of soil from the infield. The origin of the custom is unclear, but is generally credited to Kawakami Tetsuharu, who would go on to forge a career with his bat as a pro and as manager of the Tokyo (later Yomiuri) Giants. According to one account—although one that Kawakami later denied—after his school, the precursor to Kumamoto Technical High School, was vanquished in the final of the 1937 summer tournament, the young Kawakami scooped soil from the infield into a bag and scattered it on his school’s ground. Another story attributes the custom to Fukushima Kazuo of Fukuoka Prefectural Kokura High School, who in 1949 purportedly took home soil in his pockets after his team failed in their bid to win their third straight summer championship.

Players from Aomori Prefecture’s Hachinohe Gakuin Kōsei High School shed tears as they gather dirt from the infield at Kōshien after a second-round loss to Aichi Prefecture’s Tōhō High at the 2016 summer tournament. (© Jiji)

While the truth may never be known, it is easy to imagine the tradition arising naturally; high school players, moved by what Fukushima described as “the feeling that this might be the last time to stand on the field at Kōshien,” instinctively reaching down to grab a handful of the consecrated soil.

The Art of Groundskeeping

Kōshien’s all-dirt infield and natural grass outfield make it an outlier among Japan’s professional stadiums, most of which feature artificial turf. At one point, Hankyū considered planting grass in the infield, but this idea was scuttled as the wear and tear from infield players was deemed a groundskeeping nightmare. Even with the added burden, natural covering offers many benefits over artificial turf, including a reduced risk of injury to players. This has led teams like the Hiroshima Carp and Nippon Ham Fighters to choose all-natural fields for their new stadiums.

The task of grooming the grounds at Kōshien falls to Hanshin Engei. The landscaping firm’s dedicated team of groundskeepers are seen bustling around the field before games and touching up the grounds between innings. In the summer, they lug out a winding hose and spray the infield to keep down the dust, and during showers, they deftly unfurl a giant tarp against the falling rain. Their ability to make over the field during the short breaks between high school tournament games has become a spectacle in its own right, with the workers drawing accolades for their “godlike” performance.

Grounds crew members produce a rainbow as they wet the field before a game on August 9, 2010. (© Jiji)

A sudden squall brings out Hanshin Engei workers as a player watches on August 17, 2021. (© Jiji)

One might say that the careful and loving attention given to the field by generations of groundskeepers is the source of Kōshien’s longevity. Hanshin Engei employee Kanazawa Kenji, writing in a book detailing his many years tending the stadium’s grounds, describes it this way: “Every time we step onto the field, we can tell the condition of the grounds by the feel of the dirt under our feet and the tint of the soil. The darker the color, the better the job we’ve done.”

Disaster Strikes

On January 17, 1995, the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake devastated Kobe and nearby areas. While Kōshien withstood the shaking, the temblor damaged part of the stands and some of the concrete bases of the stadium’s floodlights. It also covered the infield in cracks. With the spring high school invitational a little over two months off, there was doubt whether repairs could be carried out in time. Work was done with an eye to bolstering the safety of the venue, and the stadium was ready for the scheduled March 25 start of the tournament.

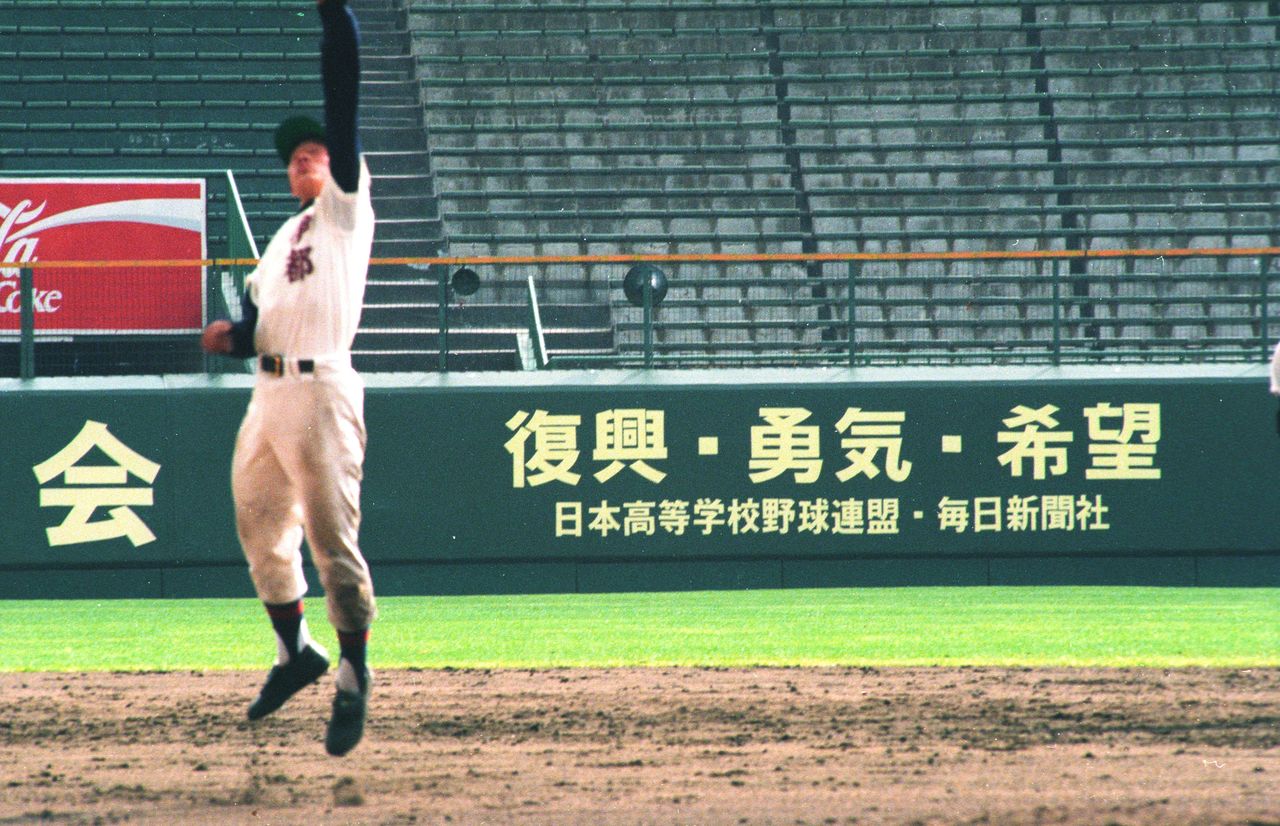

A message printed on the outfield wall after the earthquake reads “recovery, courage, hope.” Photographed on March 19, 1995. (© Jiji)

The 1995 tournament was held under the theme of “supporting recovery.” Out of respect for victims of the disaster, games were conducted amid a somber atmosphere devoid of such lively trappings as school bands and boisterous cheering. Also absent were the fireworks displays accompanying the opening and closing ceremonies.

Kōshien photographed from above on April 2, 2014, during the spring high school invitational. The roof covering the infield stands now houses solar panels, and runoff from the steel-paneled structure is collected in underground tanks for later use. (© Jiji)

The high school national championships have been canceled three times in the past—due to widespread rioting in 1918, and again due to war in the first half of the 1940s, and most recently in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Natural disaster, though, has never kept organizers from making sure the games take place. Part of the reason is the status Kōshien holds in the public imagination. This is expressed in a poem by acclaimed lyricist and poet Aku Yū that was published in daily Sports Nippon on August 8, 1995. Titled Mame maku hito (The Seed Sower), an excerpt of it goes:

Kōshien? It’s a field of dreams where sowers plant yet undeveloped talent,

Seeds whose shoots may soar and blossom in yet unknown grandeur,

The sowers, intoxicated by images of these progeny, towering and in full bloom, come year upon year to plant in earnest each little seed,

In the Kōshien ground, with a dream and a prayer.

Originally written to mark the retirement of famed coach of Sendai Ikuei High School, Takeda Toshiaki, the poem captures the spirit of Kōshien, which Aku characterizes not as a place of glory, but one where dreams are nurtured.

Players march onto the field during the opening ceremony of the summer high school championship on August 10, 2021. The tournament, cancelled the year before due to the pandemic, was held under special health restrictions. (© Jiji)

As the home of the Hanshin Tigers, Kōshien is also a place where the dreams that Aku describes come to fruition, which they did in spectacular fashion in 2023 when the Tigers won their first Japan Series title in nearly 40 years. However, it is amateur baseball that is most closely tied up in the stadium’s long legacy.

Countless sports stadiums have fallen victim to the economic winds that have dominated Japan’s postwar period. Old, historic structures are knocked down without a second thought to make room for new, lavish venues. In contrast, Kōshien’s value is of shared history and tradition, expressed in such things as the diligent groundskeepers and the carefully tended ivy. Ideas forged during Japan’s period of high economic growth need to be updated or thrown aside to fit the country’s economic reality today. I believe the history and traditions that have sustained Kōshien over the last century offer a hint of a more viable path forward.

The Hanshin Tigers celebrate winning their first Pacific League pennant in 18 years at Kōshien Stadium on September 14, 2023. (© Jiji)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The ivy-covered exterior of Kōshien Stadium, photographed on June 10, 2020. © Jiji.)