Noto Tsunami Arrived in Minutes: Did Japan Learn from 3/11?

Science Environment Disaster Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Disaster Scenes from the Noto Peninsula

Japan began the new year with a terrible natural disaster in the form of the January 1 Noto earthquake in Ishikawa Prefecture followed by a tsunami. Bearing many similarities to the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, the disaster has created a very sad and heart wrenching state of affairs. I extend my sympathies to all of those in affected areas and am committed to doing everything I can to assist. Natural disasters are always sudden and yet always different: The 2024 Noto earthquake, for its part, was a series of surprises. An active fault in the Sea of Japan produced a massive intraplate earthquake, with part of the fault expanding upward into the ocean. The JMA, Japan Meteorological Agency, issued major tsunami warnings, and on land, we saw a cascade of landslides, liquefaction, and fires. While we still do not know the full extent of the disaster, in reacting to I ask myself how much we actually learned from 3/11 and what information and support I can provide, with respect also to being more prepared for future earthquakes expected in the Nankai Trough and Tokyo regions.

The Noto Peninsula had been experiencing tremors for three years at the time of quake. On 4:10 pm on New Year’s Day, 2024, the area was hit by a magnitude 7.6 earthquake. Peak intensity was recorded at Shika, Ishikawa, which hit the maximum 7 on Japan’s seismic intensity scale; subsequently the intensity at Wajima was also revised to 7. Because of a series of earthquakes that had hit the area previously, the January quake caused significant damage to homes and other buildings, with even some structures that were in the process of being repaired falling victim. We must not ignore the delay in earthquake-proofing buildings or the accumulated effects of past tremors.

Two minutes after the quake, the JMA issued tsunami warnings for Yamagata, the Jōetsu and Kaetsu regions (Niigata), Sado Island, Toyama, the Noto and Kaga regions (Ishikawa), Fukui, and northern Hyōgo, and tsunami advisories for other parts of the Sea of Japan coast. Ten minutes later, Noto’s was upgraded to a major tsunami warning, the first such warning to be issued since the March 11, 2011, earthquake centered off the Pacific coast of Tōhoku (the megathrust earthquake that was responsible for the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami). And while Japan’s Pacific side has seen many massive earthquakes large enough to cause massive tsunamis, half of the six major tsunami warnings issued in Japan to date, including the latest one, actually covered the Sea of Japan.

The Dangers of Compound Disasters

Immediately after the January 1 earthquake struck, portions of the tectonic plate near the fault line exhibited changes that involved the ground being either pushed up or pushed down, liquefaction in flat coastal areas, and landslides in mountainous areas (photograph 1). This caused the collapse of buildings (photograph 2), fires, the blocking of rivers in hilly areas, disruption to power, water and other essential services, and damage to roads, bridges, ports, and other infrastructure.

Photograph 1: The Kawarada River was blocked by a landslide. (© Imamura Fumihiko)

Photograph 2: Earthquake devastation in Wajima’s central Kawai district. (© Imamura Fumihiko)

A few minutes later, a tsunami bore down on the Noto Peninsula (photograph 3). This is what is meant by a “cascading disaster.” For as long as the major tsunami alert was in place, the authorities prioritized the evacuation of residents to higher ground or evacuation centers, something that made it difficult to fight fires before they spread or rescue victims trapped under debris. It is the cascading nature of events that makes compound disasters so deadly. We should be reminded of the importance of seismic strengthening, fireproofing, and other precautionary measures.

Photograph 3: A scene in Hōryū in the city of Suzu. (© Imamura Fumihiko)

In the hilly tip of the peninsula that was particularly hard hit, roads and essential services to communities were cut off, causing many to be isolated. This resulted in significant damage to main roads that served as the main transit routes for both the immediate response and later recovery efforts, making it difficult to provide aid to affected areas.

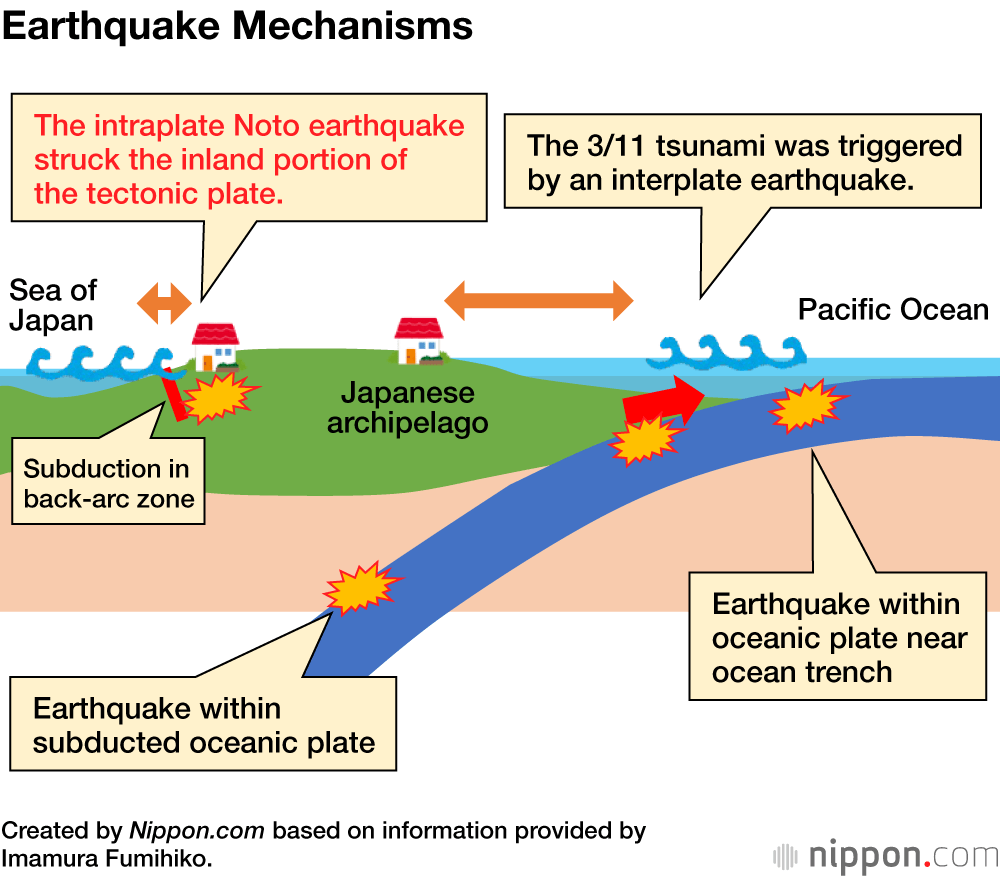

Sea of Japan Tsunamis More Sudden

Unlike interplate earthquakes like 3/11, which are caused by stresses on the boundary between two tectonic plates, land-centered intraplate earthquakes in Japan arise within just one of the plates on which the Japanese archipelago sits. While the devastation caused by this type of earthquake is not as far-reaching, depending on where the fault is, residents may receive very little warning before the arrival of the tsunami, and there may be localized amplification of tremors.

We do not tend to think of the Sea of Japan as having been responsible for many major tsunamis, but it has a long history of these disasters. A tsunami caused by a 7.8 magnitude earthquake in 1993 centered off Nansei (Hokkaidō) reached the nearby island of Okushiri in a matter of minutes. Over 29 meters high, the tsunami claimed over 200 lives. The tsunami caused by the 1983 Sea of Japan earthquake, measuring 7.7 on the Richter scale, also reached coastal Aomori and Akita in 8 to 9 minutes. This 14-meter tsunami killed over 100. Of the six major tsunami warnings that have been issued in Japan to date, three, including the latest, were for the Sea of Japan.

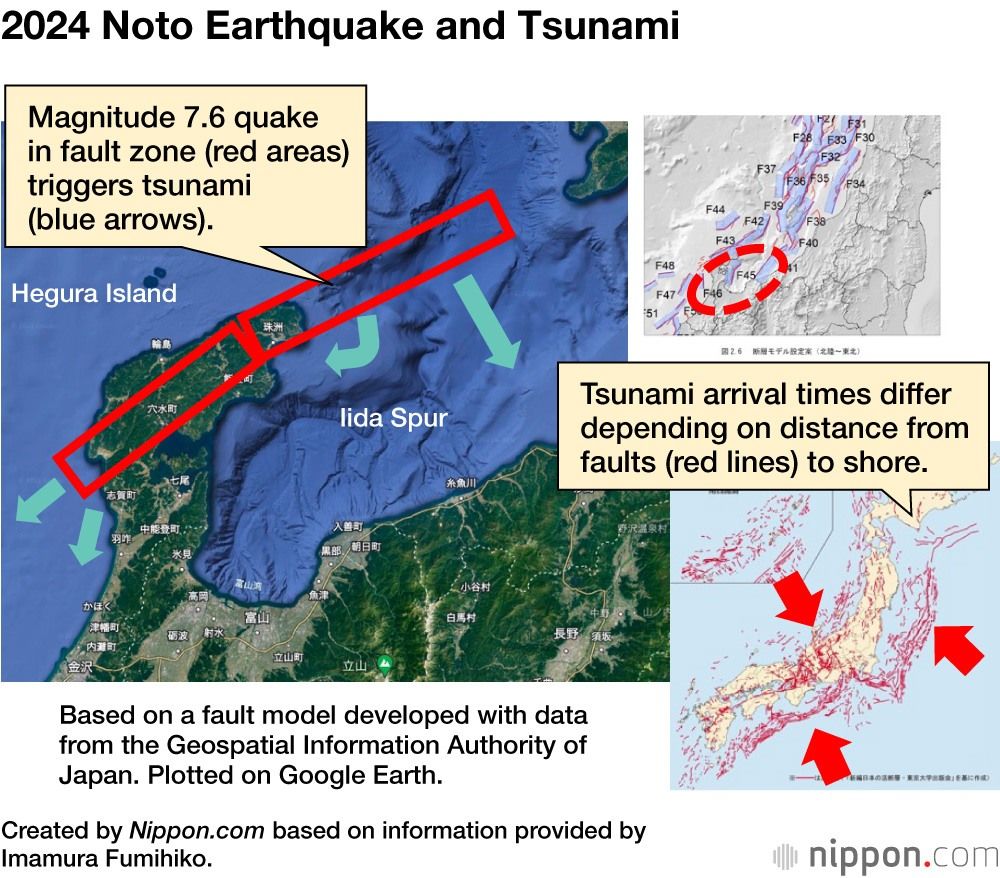

We also knew about the fault line extending north-eastward from the northern part of the Noto Peninsula. It is believed that the quake caused a 150-kilometer stretch of seabed, including the fault itself, to move inland. Coastal seabed regions were either pushed up or pulled down, causing a tsunami that arrived in seconds.

The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, on the other hand, developed at the intersection of the inland portion of the North American plate on which the Japanese archipelago sits and the Pacific plate, which is subducting under the North American plate, so its epicenter was a long way off the coast, giving residents a significant period before the tsunami arrived. The massive Nankai Trough earthquake that scientists are predicting will happen also falls into the interplate category. Earthquakes arising in the Sea of Japan, however, tend to be centered on inland faults or faults in the seabed near land. This means that these earthquakes are relatively shallow and any tsunami will reach the coast immediately. Indeed, numerical modelling estimates that the initial tsunami in Suzu, Wajima, Noto, and Nanao would have reached the coast in 1 to 2 minutes. The tsunami warning was not issued until 2 or 3 minutes after the earthquake, meaning that by the time the warning had been issued, the first waves of the tsunami had already struck the coast.

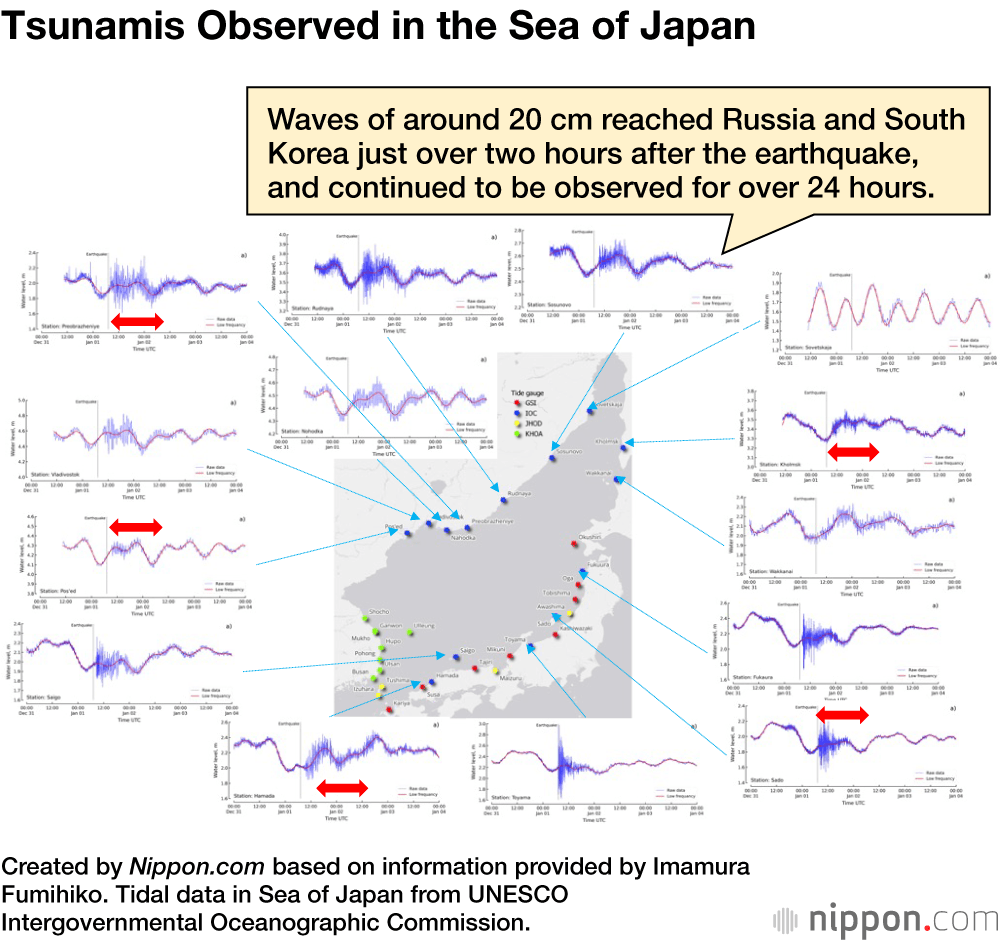

The Noto tsunami was also prolonged, with the tsunami warning remaining in force for 18 hours after the earthquake. As shown in the figure below, the Sea of Japan is confined by the landmasses of Russia and the Korean Peninsula, as well as the Japanese islands, meaning that any tsunamis arising in the Sea of Japan oscillate back and forth, taking a long time to disperse. Indeed, tide measurements show that fluctuations in sea level continued for around 24 hours after the quake. The presence of a large expanse of shallow water on the Japanese side of the sea caused the tsunami to bounce back and forth, giving rise to complex wave patterns. The recombination of these waves can result in them actually becoming amplified over time. Striking the Noto Peninsula repeatedly, the tsunami’s effects continued to be felt for an extended period.

The Effects of the Tsunami

According to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, the tsunami inundated an area of over 190 hectares in the municipalities of Suzu, Noto, and Shika. A survey performed by the Japan Society of Civil Engineers’ coastal engineering committee found that the Shika communities of Akasaki and Shishizu recorded a 5.1-meter tsunami. In Hōryū, in coastal Suzu, the tsunami gouged the coastline, causing it to erode, evidence of the power with which it hit. The tsunami also lifted boats and cars and flattened weaker buildings, carrying a stream of debris with it. One piece of evidence of the tsunami’s sheer force is the damaged asphalt everywhere. The powerful currents stripped roads bare.

While some flimsier buildings were flattened by the tsunami, many others remain intact. After the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, a powerful tsunami that formed at sea travelled far inland, destroying all structures in its path. The 2024 Noto tsunami, on the other hand, had a relatively short cycle, causing it to splash against the coast like surf, eroding the beach. However, this may have meant that some of its power was dissipated by the time it reached inhabited areas.

While we won’t know for certain until the site has been surveyed thoroughly, aerial photographs of damaged buildings suggest that their ground levels were flooded. Because the area in question lies at an elevation of 2 to 3 meters, I believe the tsunami was over 4 meters high. The flooding extended several hundred meters inland. It could have spread farther, but is regarded to have been contained as a result of tectonic shifts. I say this because analysis from the Geospatial Information Authority suggests that Suzu was elevated by the earthquake. If it had sunk, the flooding would have covered a larger area. It is believed that the reason that Wajima was not significantly affected by the tsunami was that it was pushed up significantly more than Suzu.

Did We Learn from 3/11?

So did Noto’s residents attempt to flee from the tsunami? For a start, immediately after the March 11, 2011, disaster, the government passed the Act on Regional Development for Tsunami Disaster Prevention, whereupon every prefecture was required to produce a tsunami hazard map that set forth what would happen in the worst-case scenario. Ishikawa’s hazard map was revised in March 2012 and distributed throughout the prefecture.

Residents have testified that many parts of the Noto Peninsula had conducted evacuation drills informed by the experience of 3/11, and evacuated quickly when the earthquake hit. The fact that the earthquake made people think of tsunami risk and that there were calls to evacuate shows that residents learned from 3/11. At the same time, in areas other than the Noto Peninsula, while evacuation drills were conducted in response to the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, in some cases they were not continued, and it appears that the evacuation after the 2024 Noto quake was a confused affair. Many other issues have also been identified, including traffic jams caused by people attempting to evacuate by car, and evacuation centers not being open.

Immediate Evacuation the Key

How should one best evacuate in the limited time available? While the JMA will issue warnings and alerts around three minutes after an earthquake, in some cases the tsunami will hit before this. Faults in the Sea of Japan tend to be significantly narrower and shorter than those in the Pacific Ocean. It is really important to get to high ground as soon as you feel shaking. If you are working, fishing, surfing, or swimming on the coast, you should move inland the moment you feel a strong tremor. Tsunamis also reach river mouths and banks more quickly, so you need to evacuate if you are in one of these areas, too.

An earthquake and tsunami centered on the Nankai Trough is likely in the near future. We need to form a heightened awareness of the importance of evacuation by understanding this latest compound disaster, learning from the experience, and using it to inform our future disaster preparedness. Not allowing past tragedies to be repeated is both the lesson we must learn from 3/11 and an idea that lies at the root of Japan’s civil defense culture.

While the 2024 Noto earthquake did give rise to a tsunami, I believe that the issuing of hazard maps based on forecast tsunami inundation and evacuation drills conducted in response to the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and other disasters contributed to minimizing its toll. At the same time, in several parts of Niigata, liquefaction has struck in the same place twice, and past data has once again highlighted the importance of forecasting the risk of such damage. It is important to pass on this information as well as other lessons of the past, and for this message to be passed on by everyone concerned. We also need to create an archive for the purpose of passing on the information and data that has been acquired and collated through these activities.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Smoke rises from houses in Wajima on January 2, 2024, after fires broke out in the wake of the Noto Peninsula earthquake the day before. © Jiji.)