Students and the Wealthy Drive Growth in Japan’s Chinese Community

Society World Work Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Waves of Migration Since the 1980s

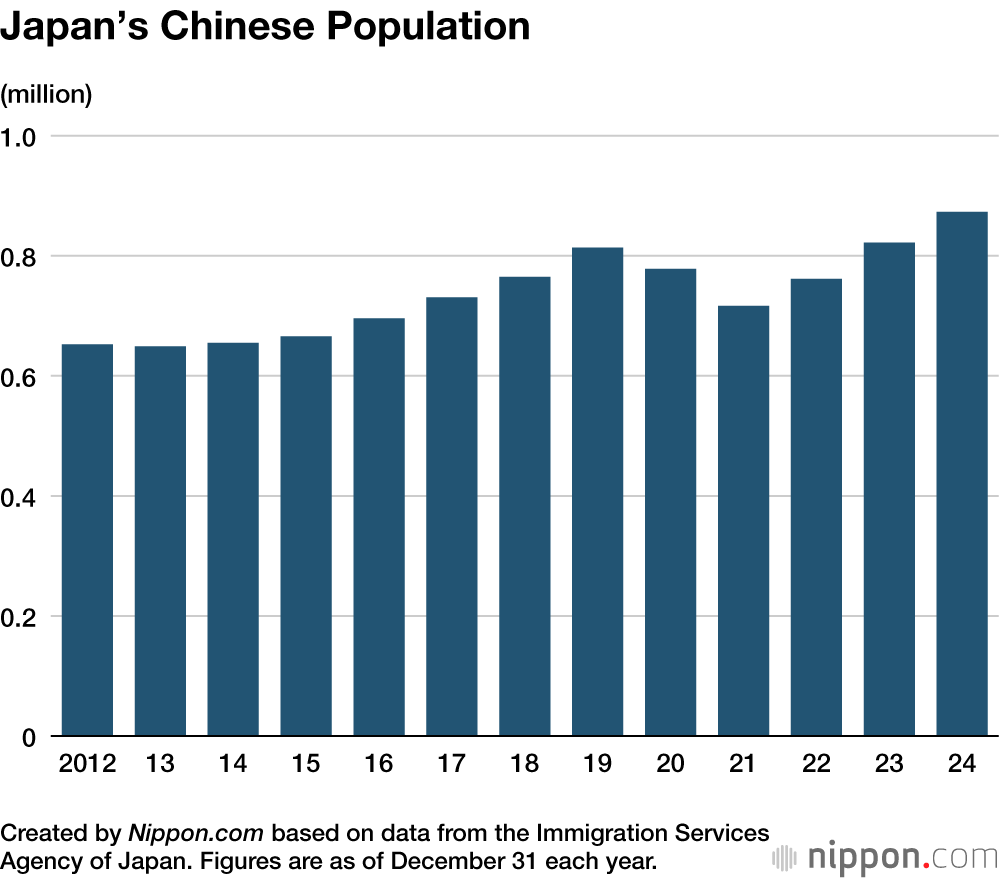

Chinese people living in Japan have become a growing presence, with the total population rising to 870,000 as of the end of 2024—2.6 times higher than in 2000. Some are fourth- or fifth-generation descendants living in Chinatowns in cities like Yokohama and Kobe. In this article, however, I will look at the shinkakyō, or new overseas Chinese, who settled after China’s reform and opening up in 1978, as well as the more recent shin-shinkakyō—“new newcomers”—and examine how these groups differ.

A store in Ikebukuro, Tokyo, selling foods targeting Chinese residents. Nearby are many Chinese restaurants. Photo taken March 21, 2025. (© Nippon.com)

In the wake of China’s economic reforms, the first arrivals were mainly government-sponsored science students in their thirties or older. By the 1980s, these were joined by younger students in their twenties, including those studying the humanities. Many returned to China after their studies, but some remained and became the shinkakyō. One woman I know came to Japan in 1985 to join her husband who was studying here. She enrolled at a Japanese university and has lived in Japan for 40 years. Her friends are in the same generation, in their mid- to late sixties, and some are already retired.

When they first arrived, there was a huge income gap between Japan and China, so even the elite, state-sponsored students had to work part time, including in physical labor. Through efforts to learn the language and integrate into Japanese society, many have established successful careers here. Some, whose parents in China have already passed away, have acquired Japanese citizenship and intend to stay permanently.

The 1990s through the 2000s saw a rapid rise in the number of self-funded Chinese students and labor migrants who are now in their forties and fifties. Many who came to study at a Japanese university were in their twenties and have since become fluent in the language. They are also well versed in the rules and customs of Japanese society, largely because they needed to adapt quickly, given that there were not as many Chinese people in Japan at the time. Their second-generation children are often native Japanese speakers.

Tokyo is home to 270,000 Chinese residents—about a third of the total in Japan—but the generation that arrived in the 1990s and 2000s has increasingly moved out to neighboring prefectures like Saitama, Kanagawa, and Chiba. More than half of residents of the Shibazono public housing project in Kawaguchi, Saitama, for example, are from China.

A Post-Pandemic Shift

The latest arrivals from China have quite different motives and backgrounds from their predecessors. These are people who came to Japan after around 2017, when the government of Xi Jinping began tightening its grip on Chinese society, even as the country gained unprecedented economic clout. Their numbers have risen sharply since the COVID-19 pandemic, and they are clearly of a younger, wealthier demographic.

These ”new newcomers” come on student or work visas, as well as under business manager visas required to run a business in Japan; according to the Immigration Services Agency, 19,000 Chinese nationals in Japan had business manager visas as of the end of 2023. The ages of the recent arrivals vary widely, from their twenties to their sixties, with most students belonging to Generation Z.

The number of Chinese people seeking to enroll in Japanese universities has increased since the early 2010s. Cram schools have capitalized on this trend, and there are now many schools for Chinese students in neighborhoods like Tokyo’s Takadanobaba. Attending only a Japanese language school is not enough to pass a university entrance exam, so many Chinese students attend both kinds of school.

A cram school poster aimed at Chinese students features former students who have gained admission to top universities, including the University of Tokyo. Photo taken in Takadanobaba March 21, 2025. (© Nippon.com)

Academically inclined students set their sights on elite national universities like the University of Tokyo and Kyoto University, as well as prestigious private institutions that are well known in China, such as Waseda University. But art colleges have also seen a sudden boom in popularity among Chinese students. This is likely because anime like Dragon Ball, Saint Seiya, One Piece, and Slam Dunk have been hugely popular in China since the late 1990s. Many who grew up watching these series and who admire the works of Studio Ghibli’s Miyazaki Hayao and Suzume and Your Name. director Shinkai Makoto now come to study animation, filmmaking, and art in Japan. Contemporary visual artists like Nara Yoshitomo and Murakami Takashi also have a huge following in China.

In the past, the parents of these students might have encouraged them to study economics, law, science, technology, or other subjects more conducive to a successful business career, but now that they are financially secure, they are more willing to support their children’s personal aspirations.

A February 8 article in the Nikkei Shimbun detailed the ongoing rise in Chinese students at Japanese art colleges; at institutions like Kyoto Seika University and Kyoto University of the Arts, they account for around 70% of all international students. While China has famous art colleges like the Central Academy of Fine Arts, their numbers are limited compared with the country’s population, making admission intensely competitive. This makes the idea of studying in Japan—the home of many celebrated creators—more attractive to many young Chinese. According to cram school teachers, these students receive generous allowances from wealthy parents in China and do not need to work part-time. During my reporting, I have encountered students who receive more than ¥500,000 each month.

“Running” from Uncertainty

Apart from students, there has been a huge recent increase in middle-class and wealthy Chinese people of all ages moving to Japan. This is not due to an interest in Japan’s economy or society but rather a desire to escape China’s restrictive policies seen during the Zero-COVID campaign in 2021 and 2022, which tightened state control over movement and information. A feeling of being trapped amid an economic slowdown prompted many to leave the country, either as a hedge against risk or out of concern about their children’s future.

During the Shanghai lockdown from the end of March to the end of May 2022, the word 润 (run) became popular in China. This has the meaning “profitable” or “to moisten,” while its romanization evokes the English word “run,” and it has been used as a form of slang meaning to flee for a better life. Many chose destinations like Singapore and Western countries, while others opted for Japan, where they could rely on established Chinese communities. Other reasons to choose Japan included similarities in the language through its use of Chinese characters, a sense of security from being in East Asia, relative affordability, and social stability. An added incentive was the Japanese government’s easing of visa requirements.

A high-rise condominium in Toyosu, Tokyo. Such residences are popular with wealthy Chinese living in Japan. Photo taken February 2023. (© Nakajima Kei)

Those in the affluent class sell their property in China or use part of their financial assets to buy luxury high-rises in central Tokyo. Many of them are well-educated corporate executives, and not a few have a negative view of China’s current political leadership. These “new newcomers” have high social standing in a country with a bigger economy than Japan. Those who own companies or maintain personal connections in China regularly shuttle between the two countries. Although they live in Japan, they do not necessarily intend to settle here for life.

The latest group of arrivals is smaller in number than earlier generations of overseas Chinese, but they have economic clout and are attuned to the latest events in China, so they have a large voice in the community. If China’s political system does not change, migration to Japan and other countries is likely to continue accelerating.

(Originally published in Japanese on April 1, 2025. Banner photo: Cram school ads for Chinese students in Takadanobaba, Tokyo. Photo taken March 21, 2025. © Nippon.com)