Failures of Noto Disaster Relief Drive Major Reforms: Japan’s Revised Laws Target Infrastructure, Individuals

Society Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

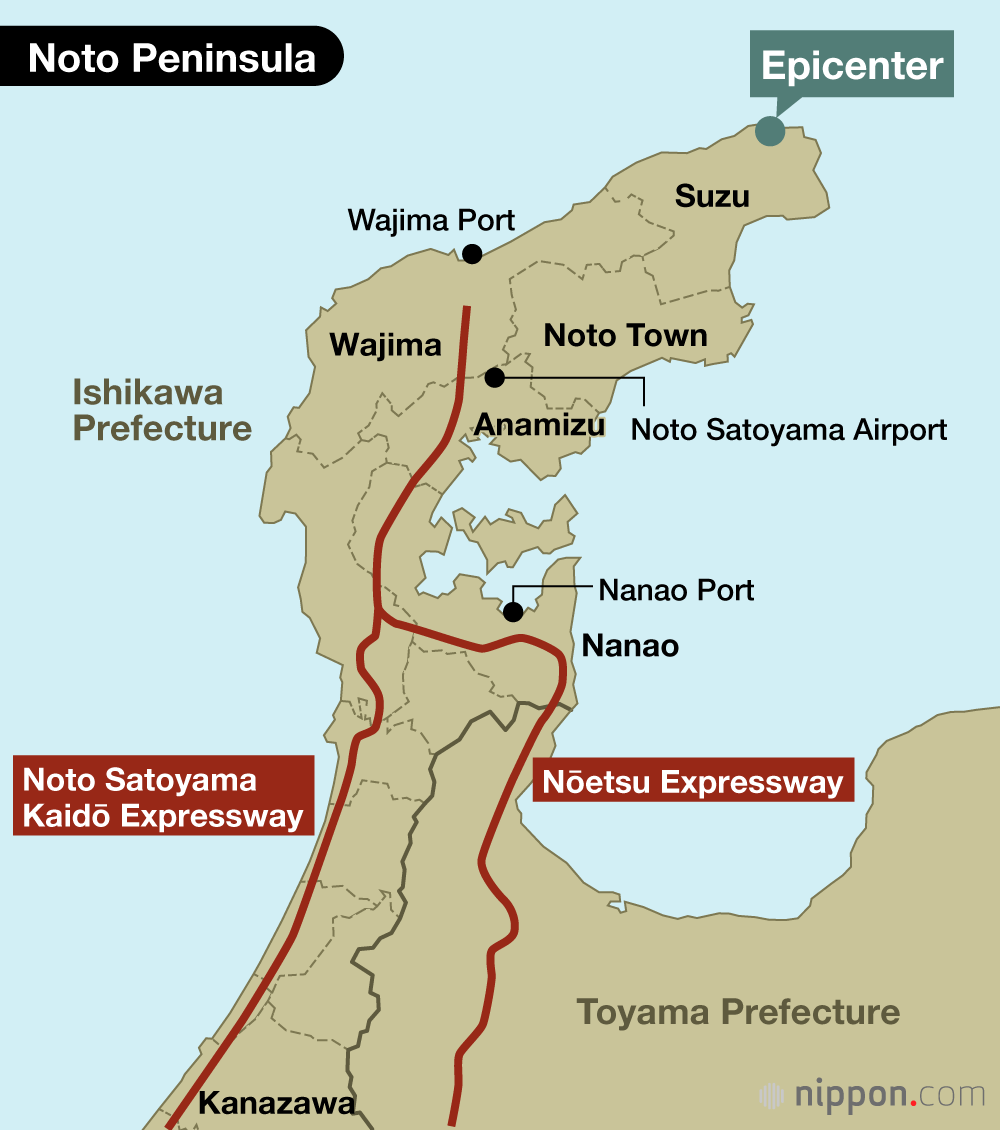

The magnitude 7.6 earthquake that struck the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture on January 1, 2024, was a devastating event. It was the direct cause of 228 deaths and a major contributing factor in another 397 (as of July 2025). Roughly 30,000 buildings were destroyed or severely damaged. Transportation arteries running the length of the remote peninsula became impassable, and the seafloor rose as much as four meters, reducing the depth of coastal waters and rendering ports unusable. The disruption of both land and sea routes greatly hampered early rescue and relief operations. The damage to infrastructure isolated rural communities, and thousands of residents were left without water, electricity, and other essential services. Communication networks were disrupted, making it extremely difficult for responders even to identify and locate those in need of rescue and relief. These factors contributed to the high number of indirect fatalities.

Anatomy of a System Failure

With victims pouring into primary evacuation centers, overcrowding became a problem, and many took refuge in makeshift shelters, including damaged homes, warehouses, plastic greenhouses, and automobiles. Owing to the number of municipal employees affected by the disaster, public evacuation shelters were inadequately staffed. Volunteers from nonprofits and other organizations quickly converged on the region, eager to assist by providing free meals or helping to run evacuation centers. But collaboration between the private and public sectors ran into numerous snags over issues of information access, use of public equipment and facilities, and responsibility for costs incurred.

Water outages were widespread, especially in budget-strapped, depopulated municipalities, which have been slow to upgrade their water-supply systems. It was estimated that restoring running water would take weeks in some areas. In a region known for its harsh winter climate, it was quickly deemed unfeasible for residents of hard-hit rural communities to remain in place, and with regional welfare services under unprecedented strain, we concluded that thousands of residents would need to be temporarily relocated. But such a large-scale “wide-area evacuation” was hampered by laws preventing municipalities from sharing personal information with other entities—public or private—that were willing to provide support and accommodation.

The aging of Japan’s rural population is particularly pronounced on the Noto Peninsula. In such quake-hit municipalities as Wajima, Suzu, Noto, and Anamizu, at least 50% of the population is 65 or older. Consequently, there was an urgent need not only for medical assistance teams to provide conventional medical care but also for disaster welfare assistance teams and the coordinated dispatch of nursing-care personnel to support elderly victims. Unfortunately, such welfare services were outside the scope of the Disaster Relief Act. This, together with the difficulty of sharing information about those in need of such services, severely hampered early relief efforts. It also resulted in a shortage of temporary housing equipped to meet the needs of elderly victims.

Victims of the Noto earthquake shelter in a plastic greenhouse in Wajima, Ishikawa Prefecture, on January 9, 2024, more than a week after the quake hit. (© Kyōdō)

Digital Technology for Victim-Centered Relief

There is widespread agreement that relief for victims of the Noto earthquake was significantly hampered by poor access to information on the disaster victims, particularly those most in need of assistance—a problem exacerbated by the Noto Peninsula’s geography and aged population.

In its November 2024 report on disaster-management lessons from the Noto earthquake, the prime minister’s Central Disaster Prevention Council called for a conceptual shift, from place-centered relief geared to public evacuation sites to people-centered relief geared to victims.

Moving proactively, Ishikawa Prefecture established Japan’s first disaster victim database with the support of other local governments, the central government’s Digital Agency, and the Disaster Prevention DX Public-Private Co-Creation Council. Having collected data provided by disaster victims with the help of the LINE messaging app, Suica IC cards, and other tools, the Ishikawa prefectural government has already begun using the database to determine the whereabouts of displaced persons with a view to improving the distribution of donations and monitoring care of the elderly. The working group involved in the system’s design and implementation has also published a set of procedures and specifications that can be used for the horizontal deployment of this resource in other regions (also with support from the Digital Agency and other government entities).

Upgrading the Legal Framework

On May 28, 2025, the National Diet passed legislation to amend the Basic Act on Disaster Management, the Basic Disaster Relief Act, and other relevant statutes. The revisions have three fundamental purposes: strengthening the national disaster response, enhancing support for disaster victims, and speeding up repair and rebuilding of infrastructure. Here I focus on revisions aimed at enhancing support for disaster victims.

Pursuant to the new legislation, the Disaster Relief Act has been revised to expand the target of aid beyond public evacuation centers and to guarantee support for “provision of social services.” The aim is to ensure adequate relief for a broader spectrum of victims, including the elderly and others with special needs, people unable to reach evacuation centers, and victims sheltering at home. The revised Basic Act on Disaster Management also explicitly calls for the provision of welfare services.

Other changes pertain to the sharing of personal information in the event of disasters requiring wide-area evacuations. In Japan, municipalities have responsibility for the delivery of government services and assistance to their registered residents, and laws governing the protection of personal information limit access to residents’ information. In the event of a disaster requiring wide-area evacuation, however, such information must be shared with other municipalities (including those in different prefectures) to ensure that displaced victims receive government services without interruption. The revised Basic Act on Disaster Management clearly calls for the prefectures’ assistance in the compilation of municipalities’ disaster victim registers. This will permit the municipalities to exchange information on displaced victims by way of the prefectural governments.

Registration of Cooperating Organizations

In the aftermath of the Noto earthquake, many NPOs and volunteer groups stepped in to assist with the operation of evacuation centers, provide meals, help residents with post-quake cleanup, and so forth. However, owing to a lack of previous experience and expertise, coordinating these contributions with the activities of the local government and the councils of social welfare proved difficult, leading to a number of issues. In an effort to avert such problems in the future, the recent revisions call for the establishment of a national registry of qualified support groups. The revised law opens the way for information sharing between such groups and affected municipalities and for government funding to support the relief efforts of those organizations.

The recent revisions also reflect an awareness of the progress Ishikawa Prefecture has made with its disaster victim database. The revised legislation expressly mandates efforts to utilize digital technology in recognition of the vital role it can play in monitoring and sharing up-to-date information on disaster victims and their movements, so that necessary aid can be delivered to individuals regardless of their location.

Disclosure of Emergency Stockpiles

A major issue that emerged in the immediate aftermath of the Noto earthquake was a shortage of emergency supplies owing to insufficient stockpiling at both the prefectural and municipal levels. Shortages were exacerbated by the fact that the quake occurred on New Year’s Day, when the permanent population was augmented by visiting relatives and tourists. Meanwhile, the earthquake and resulting landslides rendered roadways impassable, delaying the central government’s efforts to deliver additional supplies to evacuation centers and isolated communities.

In an attempt to prevent a recurrence of such problems, the revised legislation calls for concerted efforts to build adequate stockpiles, taking into account the needs of small communities that are liable to become isolated. In addition, it mandates that local governments release information on their emergency stockpiles once a year, so that residents can check on their own community’s preparedness and compare it with that of other communities.

A Multipronged Reform

The legislation passed in May revised six different statutes. In addition to the Basic Act on Disaster Management and the Disaster Relief Act, legislators revised the Water Supply Act, the Basic Act on Reconstruction in Response to the Great East Japan Earthquake, and the Act on Special Measures Concerning Countermeasures for Large-Scale Earthquakes with the aim of speeding up the restoration of vital infrastructure. They also revised the Act on the Establishment of the Cabinet Office to create a central command center for oversight and coordination of disaster management.

However, the Basic Act on Disaster Management and the Disaster Relief Act constitute the core of Japan’s disaster management policy. The Basic Act on Disaster Management was originally enacted in 1961 in response to the Isewan Typhoon of 1959 (Typhoon Vera), which left more than 5,000 dead or unaccounted for. It provides guidelines for emergency preparedness and management prior to and during disasters. The Disaster Relief Act, which deals with the provision of emergency rescue and relief, was initially enacted in 1947, following the 1946 Shōwa Nankai earthquake, and subsequently revised to expand the scope of rescue and relief.

The Disaster Relief Act creates a tiered system for disaster response, assigning primary responsibility to the prefectural governor. When a disaster on a certain scale hits a municipality or municipalities, the prefectural governor is obligated to direct, coordinate, and subsidize the relief efforts in the municipalities affected. This includes emergency shelter and temporary housing; provision of meals, drinking water, and other necessities; medical care for victims; and removal of road debris and other obstructions. The central government ultimately assumes the costs.

With each major disaster, these laws have come under scrutiny and debate as new challenges emerge. I am hopeful that this recent package of people-centered reforms, with its focus on coordinated relief and support for the vulnerable, will help reduce the number of indirect disaster-related deaths in Japan’s aging society.

(Originally Published in Japanese. Banner photo: A man in Wajima, Ishikawa Prefecture, pulls a pair of his wife’s sewing scissors from the charred remains of his home on January 4, 2024. © Jiji.)