Japan’s School-to-Work Employment System: Mass-Hiring Survives Amid New Challenges

Society Work Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Behind Japan’s High Youth Employment

Young people in every society face challenges as they transition to adulthood and strive to find their place in society. Youth unemployment in particular is a policy issue targeted by many governments around the world. However, Japan is an outlier in this regard.

The high employment rate among young adults in Japan is largely a result of the annual mass-hiring of new graduates, a longstanding Japanese business practice predicated on an ongoing need for new blood. Under this system, major companies offer graduating high school, college, and university students opportunities for permanent, or “regular,” employment while they are still in school, betting on their potential to develop the necessary job skills through in-house training. In this way, young people with virtually no job experience have generally been able to secure regular corporate jobs, which promise steady employment, periodic pay hikes, and generous benefits.

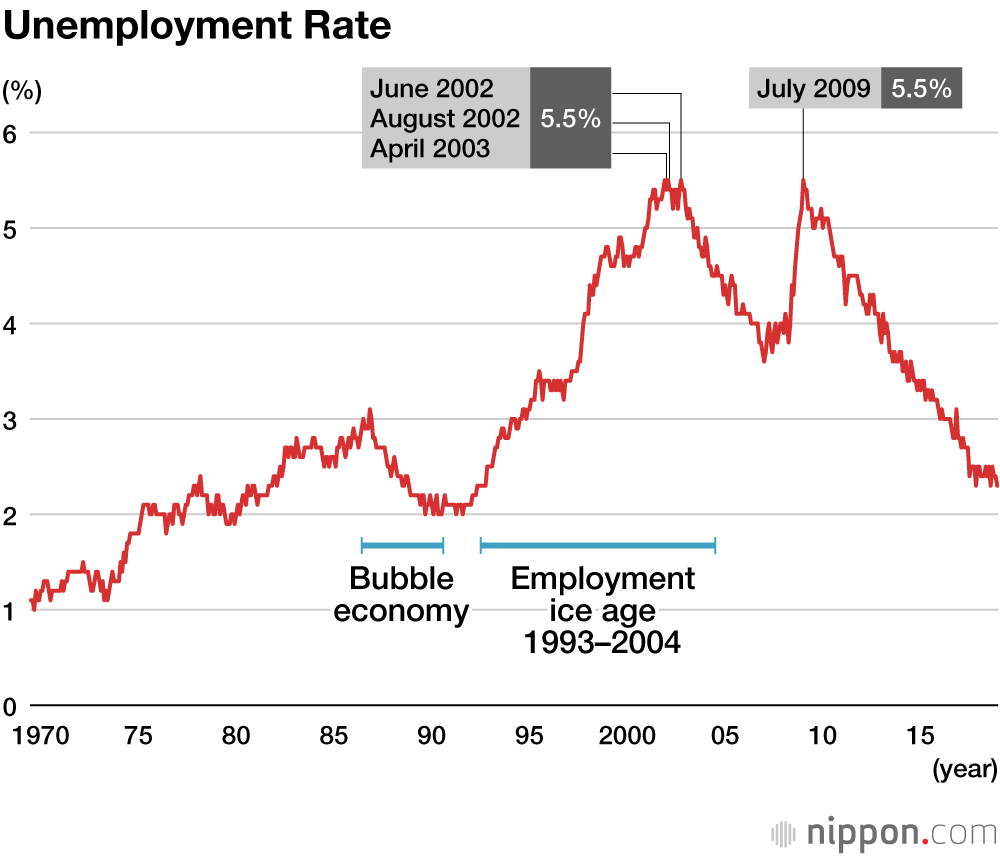

The system temporarily broke down during the “employment ice age” that followed the 1991 collapse of Japan’s asset-price bubble, as companies froze or cut back on the annual hiring of new graduates. Many of the young people who finished their studies during this era (defined for policy purposes as the years from 1993 to 2004) were obliged to settle for part-time, free-lance, or temporary work. In Japan, such nonregular young workers are referred to as “freeters.”

Recruitment of new grads for permanent positions had recovered by around 2005, as business conditions improved. The ratio of job openings to applicants dipped again during the recessions triggered by the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, but it soon rebounded, thanks in large part to the structural labor shortage caused by the aging of Japanese society. Job prospects for new graduates are by no means as certain as they were prior to the 1990s, but a good measure of stability has been regained.

That said, a significant portion of ice-agers have continued to wrestle with job instability, and the long-term economic repercussions are emerging as a social problem as this cohort approaches retirement age. The difficulties caused by the employment ice age serve as a reminder of the important role mass-hiring of new graduates has played in stabilizing careers and incomes by facilitating young Japanese people’s entry into the labor force.

Meanwhile, Japan finds itself grappling with the problem of NEETs, or persons not in education, employment, or training. In Japan, the acronym refers only to those who are neither working nor actively searching for work. The category encompasses a wide range of jobless people, including a growing number of socially withdrawn individuals known as hikikomori, as well as those impaired by illness, injury, or disability. The number of NEETs has remained high over the past couple of decades, regardless of overall employment trends.

Growth of University Education

The proportion of Japanese high school graduates enrolling in universities rose continuously from around 1950 (following the institution of the new university system) until the late 1970s, when policy measures curbing university expansion caused the ratio to plateau at about 30%. In the mid-1990s, with the 18-year-old population shrinking, the rate of university enrollment began rising again, eventually reaching the current level of around 60%. At the same time, the percentage of high school graduates directly entering the labor force has plunged from 40% at the beginning of the 1990s to around 14% today. Junior college enrollment has declined sharply over the years, but specialized training colleges—postsecondary schools providing vocational education—are the choice of roughly 20% of those who continue their education beyond high school.

The Ministry of Education estimates that the rate of university enrollment will rise to roughly 70% before leveling off in around 2040. At the same time, with the decline in the 18-year-old population projected to accelerate after 2035, the average number of university students per academic year is expected to fall from roughly 600,000 today to about 450,000 in 2040. This will force many schools to downsize or close down entirely.

From a labor-market perspective, new high school graduates overtook junior high school graduates as the largest group entering the labor force during the 1960s. In the late 1990s, university graduates took over the lead, and they now dominate the market. Students graduating from high school or specialized training colleges still occupy a significant, albeit diminished, place in the labor market. For students finishing up high school, the ratio of job openings to applicants has been on the rise in recent years.

How Young People Find Jobs

The norms and procedures surrounding job hunting by high school students vary by locale, but some generalizations can be made. While public employment agencies known collectively as Hello Work will accept applications from graduating high school students, it is the schools themselves that play the biggest role matching students to local employers in accordance with the Employment Security Act. (It is also possible, though less common, for graduating high school students to search and apply for work independently.)

High school students relying on their school’s recommendation are generally permitted to submit only one job application until the end of September, halfway through their third and final academic year. This is about two weeks after employers are permitted to begin the screening process. Some locales permit students to submit multiple applications at the start of the screening period, but such applications are relatively rare.

The process of job hunting at the university level has evolved in recent years. Through the twentieth century, university students were only able to apply to companies that formally recruited through their university’s career center or (in the case of graduate students) academic advisor. In the past two decades, however, online applications have become the norm; relatively few students now apply through their career center or academic advisor. About 70% of graduating university students rely on such platforms as Rikunabi and MyNavi for job information. Private career consulting and placement services have also emerged as significant players in recent years, currently accounting for about 10% of job applications from new university graduates.

Over the years, timetables have been put in place to prevent recruitment and job-hunting activities from interfering with students’ education. The Guideline on Recruitment and Selection published by Keidanren (Japan Business Federation), which replaced a longstanding agreement among employers and universities, called on companies to hold their recruitment events for third-year university students no sooner than the beginning of March (near the end of the academic year) and to delay the screening of fourth-year students, including assessments and interviews, until the following June (about ten months before graduation). Keidanren abandoned those guidelines in 2021, but the Japanese government continues to urge companies to abide by that schedule. Compliance is by no means rigorous, but judging from students’ job-hunting activities, the most popular firms conduct their recruitment and screening with this administrative guidance in mind.

Growing Importance of Internships

In 1997, the government gave the green light to job internships for university students on the condition that they were designed for educational purposes. More recently, it opened the door to internships as a means for employers to gather information on and recruit students for future employment. Amid labor shortages and stiff competition for new university graduates, companies have been making maximum use of this tool, with the result that about 70% of university students now take part in some internship program, typically in their third year. Indeed, third-year students generally regard the start of these internships in the fall as the de facto opening of job-hunting season. With application screening taking place the following June, the entire process spans a period of about nine months for the majority of students. This can be considered too long or too short, depending on one’s viewpoint. But certainly students stand to gain from a meaningful pre-graduation work experience, provided it does not interfere with their studies, and telework options can reduce the time demands internships place on students.

All of that said, the percentage of students that find a permanent job at the company for which they interned remains relatively low, suggesting that the system has yet to exert a major impact on the hiring of new graduates.

Declining Motivation Among New Hires

To a considerable degree, then, the mass-hiring of new graduates continues to facilitate students’ smooth transition into the labor force. But how well does that system function in terms of matching students to satisfying jobs and rewarding careers?

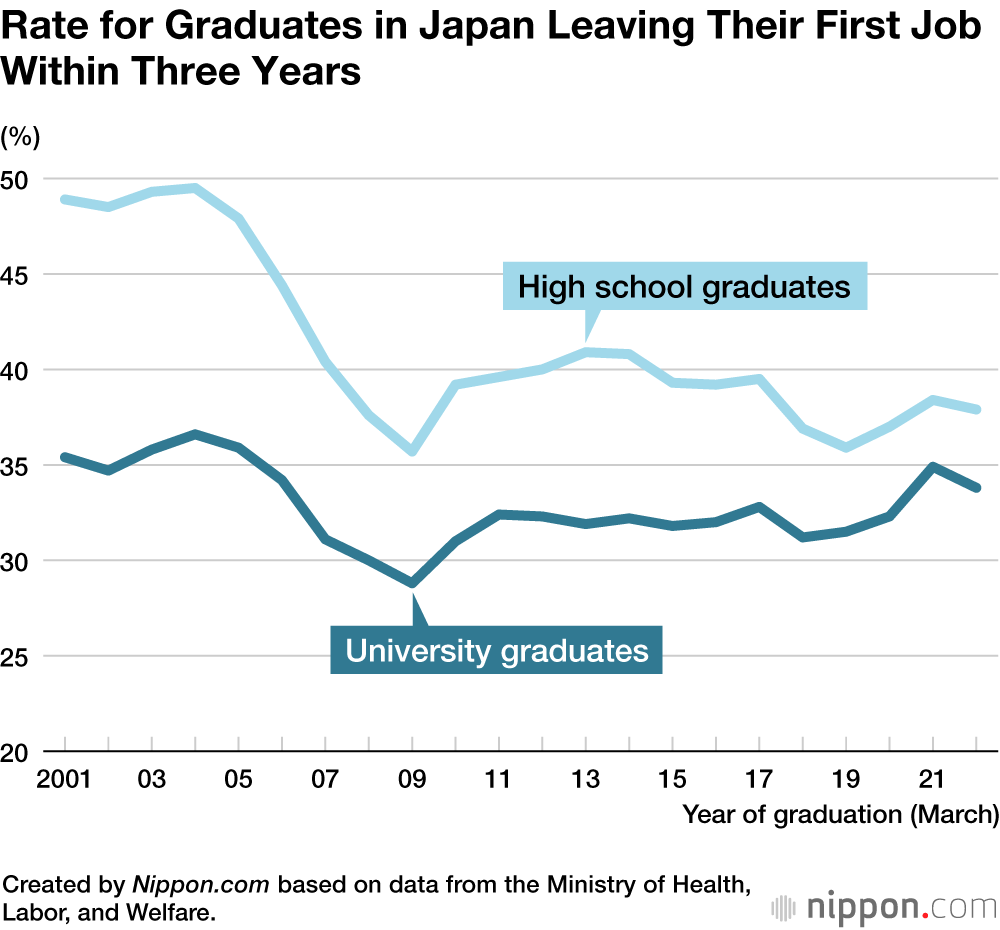

Labor mobility is relatively low in Japan. The percentage of recruits who left their first job within three years of graduating spiked during the employment ice age, but has since stabilized at a manageable level, especially among high school graduates. Other problems are surfacing, however.

I have conducted a survey of young people’s employment patterns and work attitudes every five years since 2001. In recent years, I have observed a significant change in the way permanent employees view their jobs. Until recently, regular employees who remained at the company that recruited them from school (here termed “established employees”) for at least three years were more apt to rate their jobs as worthwhile than those who had switched jobs. Since 2021, however, that trend has reversed itself, with established employees less apt to view their work as rewarding than those who transferred from other companies. At the same time, compared with earlier cohorts, today’s established employees express little interest either in switching employers or in striking out on their own. They see themselves staying put indefinitely, even if they get little or no satisfaction from the work they do. This does not necessarily bode well for their employers.

As a general trend, young people today are less committed to their jobs than previous generations. However, among permanent employees who have changed jobs in the first three years and thereby explored other career options to some degree, we see a decline in the percentage of respondents who say they do not know what sort of work really suits them. By contrast, those who have stayed with their first employer are increasingly apt to question whether they have found the line of work to which they are best suited. Poor communication between management and younger employees may be part of the problem.

From Job Quantity to Job Quality

As we have seen, the Japanese recruitment and employment system is designed to facilitate the transition from school to work. Although the system broke down during the employment ice age, it has since recovered and functions as intended for the majority of young people completing their studies. Of course, any major recession could destabilize the process once more, but amid ongoing shortages of young workers, difficulties on the order of those experienced by the ice age generation are unlikely to recur.

Still, challenges loom. Although the employment ice age is behind us, economic growth remains slow, and artificial intelligence is poised to take over a wide range of jobs. Under these conditions, the proliferation of NEETs and other disengaged youth could emerge as a social problem of major proportions. The lack of motivation and ambition among established employees is another cause for concern. Looking ahead, we may need to begin dealing with youth employment from the standpoint of quality as well as quantity.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: New Japan Airlines employees launch paper airplanes during a welcoming ceremony at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport, April 1, 2025. © Jiji.)