Tax-Cut Proposals Threaten Japan’s Social Stability: Assessing Social Security’s Costs and Benefits

Society Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Rise of Short-Sighted Populism

Responding to public angst over the rising cost of living, Japan’s political parties are falling over each other to boost workers’ take-home pay by reducing the tax and social security burden. Among the measures on the table are an increase in the minimum taxable income, a cut in the consumption tax rate, and—most problematically—a reduction in social insurance premiums.

The impulse behind this trend is understandable. With the cost of living rising faster than wages, frustration over dwindling disposable incomes is mounting, and politicians are anxious to respond with concrete measures. But government policy is about more than quick fixes to immediate problems. Taxes and social insurance contributions may be burdens, but they are also tied to benefits. Ignoring the importance of those benefits while competing to relieve the burden is the kind of short-sighted populism that debases and erodes our democracy.

What is the purpose of social security, and why has it been ensconced as one of the pillars of our modern society? By losing sight of this basic purpose, we are risking the stability of people’s livelihoods and the prosperity of the nation as a whole. In the following, I would like to reframe this emotionally charged issue on the basis of hard facts.

Japan’s Social Security Burden Is Stable

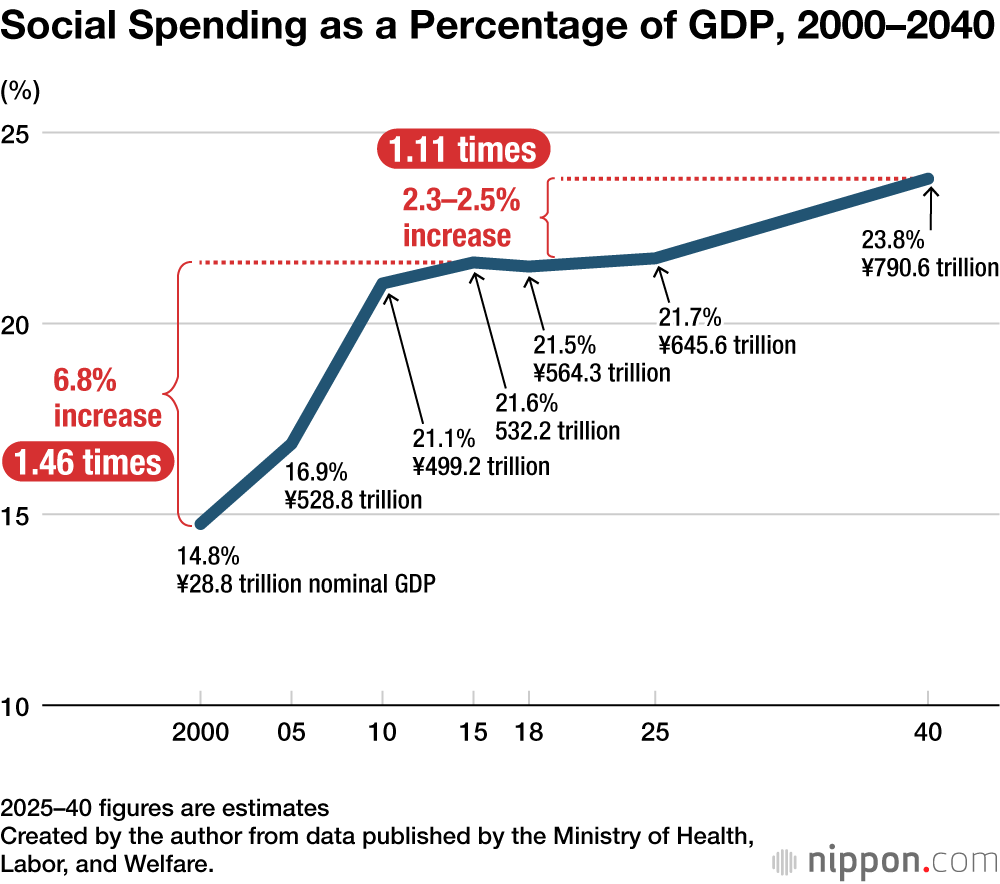

The way to measure the scale of a country’s social security system (that is, government spending on pensions, healthcare, and other social programs) is not as an absolute value but as a percentage of gross domestic product. Measured in this way, social spending is growing at a very modest pace. In 2024, according to the Japanese government’s projections, such spending will amount to approximately 24% of GDP, just 1.1 times (10%) higher than the 2015 figure.

It is true that the level of social benefits rose substantially earlier in this century, growing 1.46-fold as a percentage of GDP. This means that the burden rose significantly as well. But between now and 2040, the growth in social benefits as a percentage of GDP will slow significantly, rising by little more than 2 percentage points overall. The average annual increase in benefits during that time will amount to only about 2%. Given that the number of people 75 or older is expected to grow 1.37-fold during the same period, this rate of increase is quite restrained.

There are a number of factors behind this trend, including population decline and various policy measures designed to “structurally optimize” such national social programs as health insurance, long-term care insurance, and public pensions. Pension reforms, including the adoption of the “macroeconomic slide” formula (limiting cost-of-living increases), have played a particularly important role in this regard, reducing the level of pension benefits paid out as a percentage of GDP. We need to look at all the numbers—not just harp on past trends—in order to engage in productive debate on the issue.

Premiums Also Under Control

With regard to the burden of social insurance premiums on the working generation, public pension contributions are already fixed at a rate of 18.3% of wages and will not rise further.

Health insurance premiums are also fairly stable. Since 2012, premiums for enrollees in a Japan Health Insurance Association plan, available to employees of small and medium-sized companies, have held steady at around 10% of monthly remuneration on average. Moreover, these plans recorded an aggregate surplus of ¥658.6 billion last fiscal year. The premiums for employer-sponsored plans provided by larger companies (society-managed health insurance) are lower still, falling somewhere between 9.0% and 9.5% of earnings. (Last year, society-managed plans ran a total deficit of about ¥380 billion; the average rate required to break even is 9.6%.)

Of course, health insurance rates are bound to creep up over time as our society ages and medical science advances. This is a global problem. There is no industrially advanced country in the world today that has been able to keep healthcare costs from growing faster than GDP over the medium-to-long term. On the other hand, medical advances benefit society and its members by improving health outcomes. The only way to prevent increases in the health insurance burden would be to limit benefits in a way that conflicts with the basic principles of our system of universal health coverage.

Spotlighting Economic Inequality

Much of the economic frustration we see in Japan today relates to the growing gap between rich and poor. The current political situation in Japan is evidence of sharp social divisions fueled by growing economic inequality. One of the basic functions of social security is to mitigate inequality through the redistribution of income.

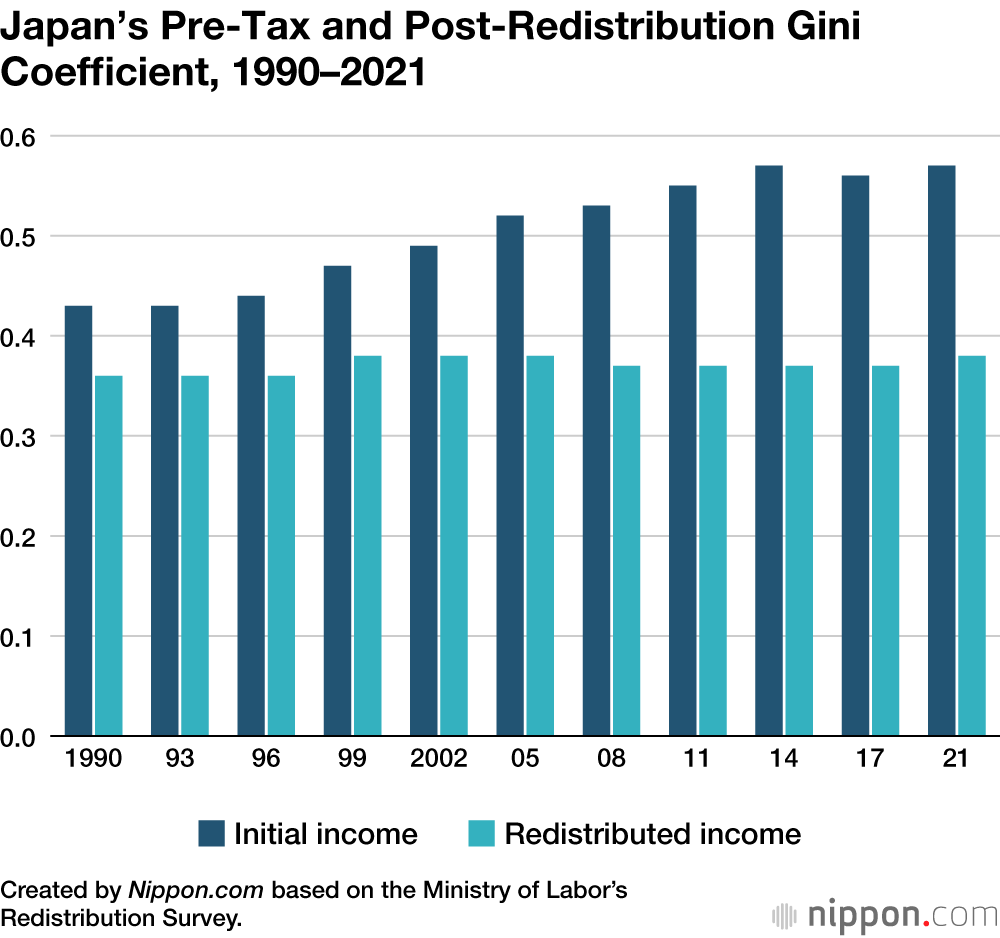

According to the Income Redistribution Survey conducted by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Japan’s pre-tax Gini coefficient, measuring inequality in initial (or market) income, has been growing. But the coefficient for disposable income following redistribution has remained virtually unchanged since 1990. Most of this redistribution occurs through government spending on healthcare, pensions, and other social benefits.

Despite this income redistribution, the gap between rich and poor has widened owing to the market’s unbalanced distribution of wealth, that is, the value generated by economic activity. Globalization has led to the concentration of wealth in certain strata and certain businesses. The pent-up dissatisfaction of those “left behind” by globalization is the root cause of the political strife sweeping Japan and other countries.

The OECD has repeatedly pointed out that widening disparities in income and wealth have a negative effect on medium- and long-term economic growth. These disparities only heighten the need for social programs to redistribute income. Too much emphasis on the burden of social security risks weakening its redistributive function, leading to even greater economic inequality and the breakdown of the middle class. This would run counter to the government’s avowed commitment to fostering a large, strong middle class at the core of Japanese society, as well as its goal of building a social security system that serves all generations.

Lower Premiums Would Favor the Wealthy

Most of the taxes and premiums supporting social security are a fixed percentage of income (or cost in the case of the consumption tax), which means that those with high incomes pay more. Benefits, on the other hand, are provided according to need. When it comes to healthcare and other social benefits provided in kind, there is no significant disparity in benefits from one income bracket to the next. What this means is that upper income brackets shoulder more of the burden relative to the benefits received. This is one way in which social security redistributes income.

In his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, French historical economist Thomas Piketty explains that modern redistribution is not a matter of transferring money from the wealthy to the poor. Rather, he says, it “is based on a set of fundamental social rights: to education, health, and retirement.”

Reducing the social security burden would require a commensurate cut in benefits, thus weakening the basic functions of social security. While the cuts in benefits would be spread evenly across all brackets, including low- and middle-income taxpayers, the reduction in contributions would disproportionately benefit high-income taxpayers and businesses (which share the cost of premiums with their employees) disproportionately. In this way, such a reform would exacerbate economic disparities.

Addressing the Market’s Unbalanced Distribution

In short, reducing taxes and social insurance premiums to boost take-home pay would ultimately undermine one of social security’s basic functions, that of supporting economic and social stability by mitigating disparities in income and wealth. In the medium to long term, such a reform would also blunt economic growth.

Income security for the working generation should be achieved not by cutting taxes but by correcting the market’s unbalanced distribution of wealth. The basic problem confronting Japan is that growth in productivity and profitability have not been adequately reflected in wages. This fundamental distortion in the market’s distribution of wealth is the issue our politicians and policy makers should be addressing today.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A participant in the 2023 May Day rally at Yoyogi Park organized by the National Confederation of Trade Unions holds a sign calling on the government to lower the consumption tax. © Jiji.)