Yamagami Sentencing Reveals Japan’s Troubled Response to Religious Cults

Society Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Life Sentence for Yamagami

On January 21, Yamagami Tetsuya was sentenced to life imprisonment for the July 2022 murder of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō. Courts typically exercise judicial discretion in sentencing, departing from what prosecutors demand, but in an unusual move, the Nara District Court followed the prosecution’s recommendation in full in passing down punishment.

One factor that made this case different was the array of charges Yamagami faced. Along with the main charge of murder, Yamagami was also tried for violating Japanese laws prohibiting the possession, manufacture, and discharge of firearms, as well as property damage. The defense attempted to win acquittal on the firearms and weapons manufacturing counts, arguing that Yamagami’s homemade weapon did not fall under applicable statutes. Acquittal on these counts would have bolstered their case for limiting sentencing to no more than 20 years, but the court rebuffed this line of argument, clearing the way for a harsher punishment.

Another factor was Yamagami’s perceived unrepentance. In cases where a court grants the prosecution its sentencing request, the judge will typically consider the defendant as not having shown adequate remorse or not apologizing for the crime. In passing judgement on Yamagami, the bench noted that he had demonstrated neither an understanding of the danger of his actions nor the gravity of taking another human’s life, and so could not be said to have reached a sufficient level of remorse.

While Yamagami did express regret, the court in coming to its decision seems to have put greater weight on both his failure to apologize directly to Abe’s widow Akie and to make any attempt to atone for the killing, such as through financial restitution.

Defendant’s Background Dismissed

Another critical point in Yamagami’s sentence was the court brushing aside his troubled background as a second-generation follower of the Unification Church, which was central to the defense’s case. The ruling acknowledged that Yamagami, who stated that his motive stemmed from the financial duress his family suffered at the hands of the UC, may have “harbored intense anger” toward the organization and its affiliates (including politicians like Abe, whom he viewed as having supported the church) and a desire to make them suffer, but it stressed that there was “a significant leap” between those feelings and planning and carrying out murder with a homemade weapon. Judging the leap too great, the court dismissed the defendant’s upbringing as not having a substantial influence on his crime.

This was a surprising development given the growing understanding of how childhood trauma can profoundly influence the trajectory of a person’s life. This connection is particularly relevant in lawsuits by second-generation followers against religious groups like the UC, as demonstrating the long-lasting effects of adverse childhood experiences enables claimants to win greater compensation for their suffering.

At the heart of Yamagami’s case was his decision to assassinate the former prime minister rather than directing his deep-seated resentment at the UC itself, or its leaders. Abe had connections to the Unification Church, and the court weighed whether the killing was a leap too far or an inevitable outcome of childhood trauma, with the judge ultimately choosing the former. A likely factor in this outcome was the failure of the defense to present expert testimony from psychiatrists or other mental health experts in order to clearly link the suffering inflicted on Yamagami by the church during his formative years with his later crime.

South Korea and the Dissolution Order

Looking at Yamagami’s case, one must also consider the potential impact of the investigation of the Unification Church in South Korea, where the organization is based. Of particular interest are a raft of documents known as “TM Reports” seized by investigators while probing the UC’s attempts to influence former Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol’s administration. The reports, linked to the church’s leader Han Hak-ja, who goes by the title “True Mother,” shed light on the UC’s connections to leaders in Korea, but are also purported to contain extensive information about the church’s relationships with Japanese politicians. Han has already been arrested and indicted, and depending on how the South Korean investigation unfolds, more of the nature and extent of Abe’s ties to the UC may come to light.

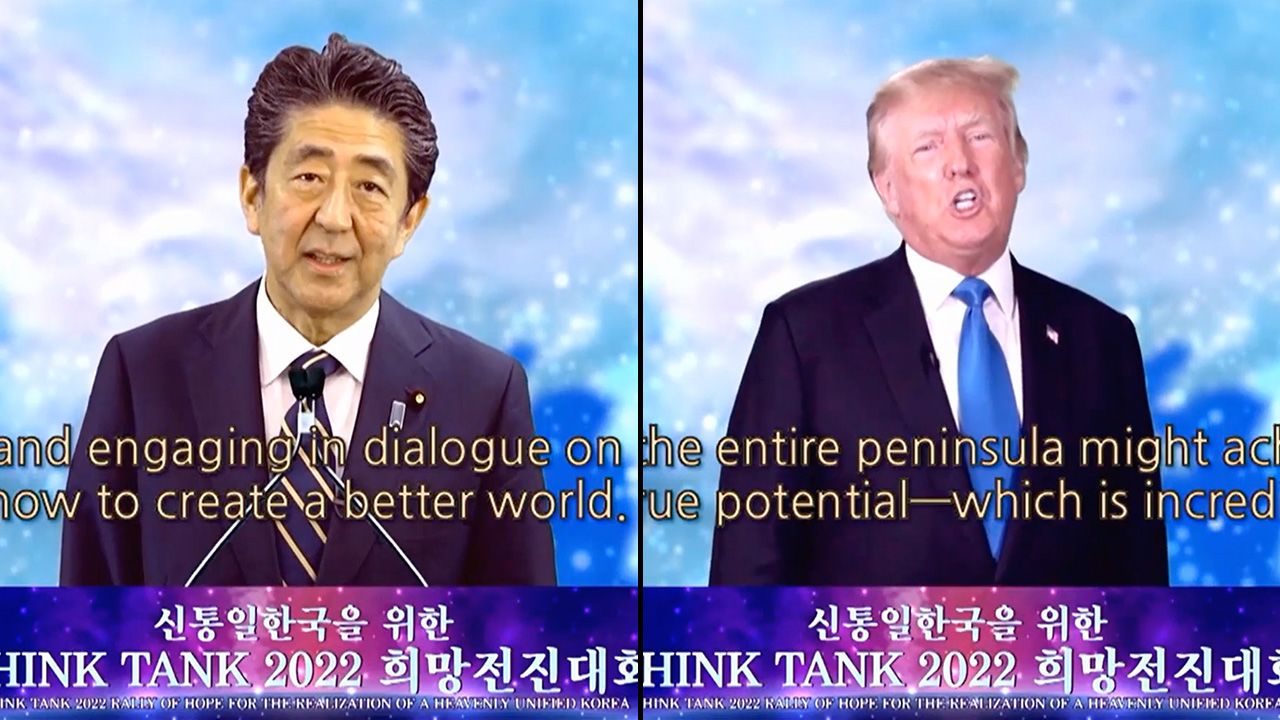

An incident that has drawn much scrutiny involves a video message Abe made for an event organized by a church-affiliated group in September 2021 in which he expresses his respect for Han. Many aspects of Abe’s relationship with the Unification Church remain unclear, which leads to the question of what impact a full understanding of the UC’s political connections would have had on the course of the Yamagami trial. The lack of such insight is deeply regrettable for criminal proceedings, which should be unwavering in the pursuit of the truth.

Political connections are just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the problems surrounding the Unification Church that Abe’s killing brought to the fore, most of which remain unresolved three and a half years after the incident. Yamagami’s sentencing is unlikely to have an immediate effect on litigation over the dissolution of the UC, which the Tokyo District Court ordered in March 2025. Following a church appeal, the case went to the Tokyo High Court, which is expected to issue a new ruling in March 2026; for now, liquidation of the UC’s considerable assets, through which victims would receive compensation, cannot proceed. It is worth contemplating the potential impact on Yamagami’s trial had the dissolution order been finalized and the full extent of the church’s harmful activities been exposed.

Failing Second-Generation Victims

In the wake of Abe’s shooting, the Japanese government quickly passed legislation prohibiting the unjust solicitation of funds by religious organizations, dealing a blow to the coercive fund-raising tactics of the UC. The law, however, is short-sighted. It focuses primarily on the harm inflicted on followers like Yamagami’s mother, whose massive donations to the church ruined her family financially. What is more, it only vaguely addresses the deceptive tactics that drew her and others in in the first place in its demand that organizations give “sufficient consideration” to followers when soliciting donations. Subsequently, it provides almost no protections for second-generation victims.

The law was subject to review after two years, but in September 2025 the Consumer Affairs Agency announced that while it would continue implementing the legislation, it saw no need for revision at present, effectively shelving its obligations to victims. Consumer protection efforts must extend to those families still struggling, yet the agency has shown little willingness to carry out this role, leaving second-generation victims like Yamagami to fend for themselves. Moreover, compensation standards for abuse victims under the Child Abuse Prevention Act, which has yet to be updated to reflect current situations, remain woefully inadequate.

“Foreign Agents”

Legislators have also been lax in taking up the issue of political infiltration. The recent introduction of anti-espionage legislation has sparked a modicum of debate over lobbyist regulation, but in light of the Unification Church’s success at currying favor with leading politicians, a brazen case of foreign influence in Japanese politics, there needs to be a more concerted effort to address such risks. Japan must draw up legislation in the vein of the US Foreign Agents Registration Act and similar laws adopted by European governments that impose disclosure obligations on individuals representing foreign interests. In the United States, for instance, FARA was key to the 1984 imprisonment of Unification Church founder Sun Myung Moon, on tax evasion charges.

Hindsight is 20/20, but it strikes me that so much suffering could have been avoided had those in power in both Japan and South Korea not waited to act against the UC. Had the South Korean government launched its investigation into the church earlier, Abe might never have sent his 2021 video message, and the shooting itself might never have occurred. If victim relief for former members and others had not been neglected in Japan, the Unification Church would likely not have been able to funnel donations attained through coercive means toward political influence operations in Japan and South Korea. The last point is a strong argument for the need to strengthen legislation against money laundering in both countries.

More importantly, though, there needs to be better appreciation of the need for victim relief and understanding of political infiltration by cults if effective countermeasures are to be put in place. Cults like the Unification Church are a universal threat, and France provides an example in having drawn up 10 criteria that focus on deviant behavior of sectarian movements that threaten public safety or human rights.

Aum’s Long Shadow

Finally, it is difficult not to see the Yamagami case in terms of the legacy of Aum Shinrikyō. Since the shocking sarin attack on the Tokyo subway by the religious cult in 1995, Japan has spent the ensuing three decades in a daze in terms of dealing with cults, with no effective countermeasures being put in place. This failure has enabled cultlike religious organizations to continue to prey on the innocent. In fact, Japan has yet to work out why the sarin attack happened in the first place or how to prevent a similar tragedy from occurring in the future.

In finding answers to these questions, Japan should draw on foreign legal frameworks like France’s anticult laws. The harm and suffering inflicted on second-generation members of cults is an ongoing human rights crisis that can no longer be ignored.

Some have suggested that Prime Minister Takaichi Sanae timed her dissolution of the lower house of the Diet on January 23 to head off renewed scrutiny of ties between the ruling Liberal Democratic Party and the Unification Church in the wake of the Yamagami verdict. I believe, however, that it may instead thrust the UC issue back into the spotlight. The long absence of cult countermeasures is a responsibility shared by society as a whole, including the media. The election may well finally force Japan to contemplate the lack of action in the 30 years since Aum.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō and former US President Donald Trump delivering video messages to a September 2021 event hosted by the Universal Peace Foundation, an organization affiliated with the Korean Unification Church. From the UPF website.)