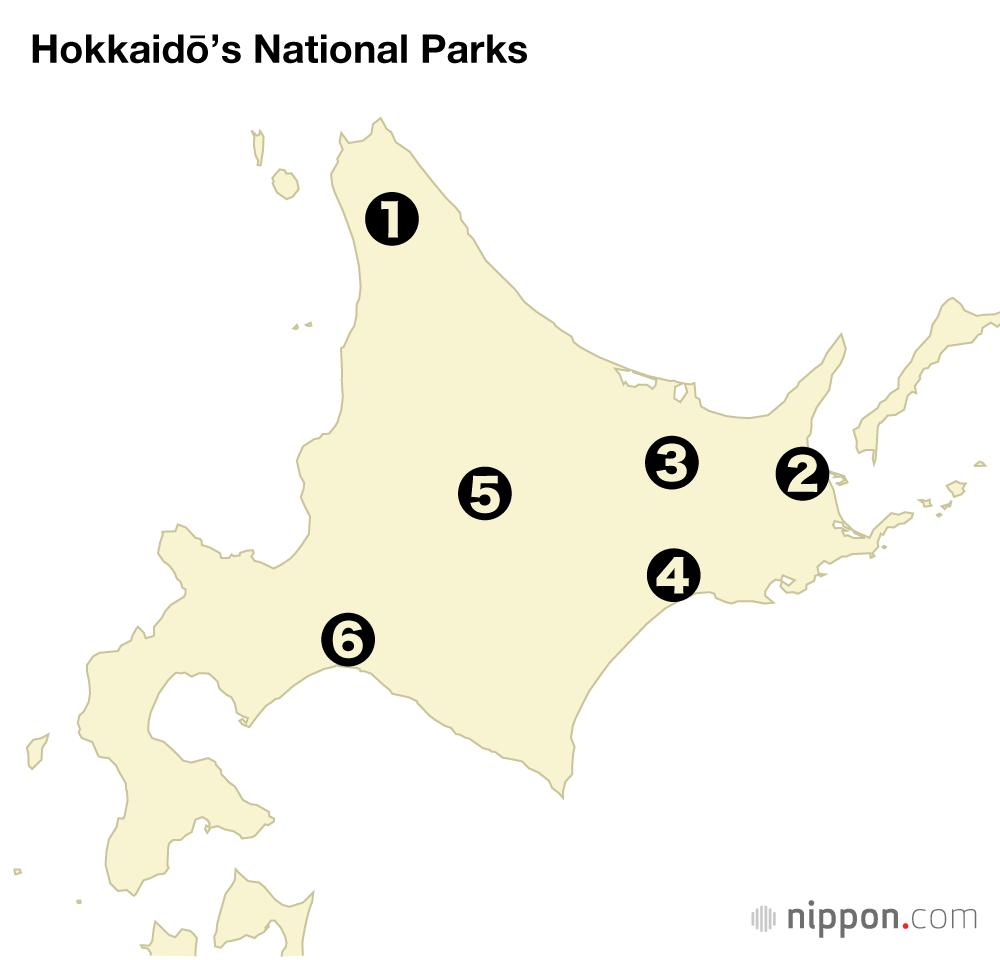

Hokkaidō’s Six National Parks

Environment Travel Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

1. Rishiri-Rebun-Sarobetsu National Park

Sea cliff topography of Rebun Island. (Courtesy Ministry of the Environment)

View of Mount Rishiri in summer. (Courtesy Ministry of the Environment)

Japan’s northernmost national park boasts a rich variety of landscapes that include mountains, sea cliffs, bogs, and coastal dunes. Mount Rishiri (also known as “Rishiri Fuji”) has a beautiful conical shape and, as an offshore mountain, offers splendid ocean views to climbers.

Visitors to Rebun Island have the chance to see rare alpine plants like Cypripedium macranthos orchids growing in lowland fields, while the west side of the island has dramatic cliffs and rock formations.

The Sarobetsu Plain contains one of Japan’s largest high-level areas of wetland stretching out over peaty soil, and is a stopover point for wild migrating birds like geese and ducks.

(Date of designation: September 20, 1974. Area: 24,166 ha.)

2. Shiretoko National Park

Furepe meadow in winter. (Courtesy Shiretoko Nature Foundation)

At Furepe Waterfall, groundwater seeping out from the cliffs flows directly into the sea; the waterfall is also known as “Maiden’s Tears.” (Courtesy Shiretoko Nature Foundation)

Shiretoko, derived from the Ainu phrase sir etok, meaning “the end of the earth,” is located at the extreme eastern edge of Japan. The national park is characterized by a steep, majestic landscape formed by volcanic activity and drifting ice, and abundant wildlife. A rich variety of creatures coexist in this ecosystem, including large mammals like brown bears and orca as well as large endangered birds of prey, and the park is managed in such a way as to preserve this diversity. The management was recognized in July 2005 through the registration of Shiretoko National Park as a World Natural Heritage site.

The most popular view in the park is the scene of the lush surrounding forests and the Shiretoko Mountain Range reflected in the waters of a lake set within the primeval forest (see the banner photo).

(Date of designation: June 1, 1964. Area: 38,636 ha.)

3. Akan-Mashū National Park

Lake Onnetō is a body of water with a 2.5-kilometer shoreline at the foot of Mount Meakan. The waters of the lake change from blue to emerald green to dark blue, depending on the season, the weather, and the angle of viewing.

View of Mount Oakan in winter.

The park is centered on three caldera terrains—Akan, Kussharo, and Mashū—created by the Chishima volcanic belt. It is unusual in Japan to have a landscape where a volcano and a lake are in such close proximity. Natural forests, primarily subarctic coniferous trees, cover most of the park, making it one of Japan’s national parks with the most primitive landscape.

The Akan region is known for the majestic Mount Oakan and Mount Meakan and the beautiful scenery of Lake Akan and Lake Onnetō. The Mashū region, whose forest scenery changes from season to season, features Lake Mashū, one of the world’s most transparent lakes, and Lake Kussharo, which can be looked down on from the surrounding peaks and mountain passes.

(Date of designation: December 4, 1934. Area: 91,413 ha.)

4. Kushiroshitsugen National Park

The panorama of the Kushiro Marsh with the setting sun in the distance. (Courtesy Pakutaso)

A steam locomotive running through the Kushiro Marsh.

The park includes Japan’s largest marsh, which encompasses the Kushirogawa river running through east Hokkaidō and its tributaries, as well as the surrounding hills. The area is a precious habitat for many flora and fauna, including the red-crowned crane, which has been designated a “natural monument.”

The marshlands were long thought useless because of the difficulty of raising crops on them, but after World War II, due to food shortages, the land was cultivated, cities developed, and the hilltops sheared off, which resulted in a reduction in the marshlands and the drying out of the land. This led to a movement among local researchers and environmental groups to renew appreciation of the marshlands, resulting in the area becoming the first Ramsar Site registered in Japan in 1980, and the designation as a national park seven years later.

(Date of designation: July 31, 1987. Area: 28,788 ha.)

5. Daisetsuzan National Park

View of Mount Asahidake and the frozen Kagami Pond in winter. (Courtesy Ministry of the Environment)

Flowers growing on slopes of Mount Nipesotsu. (Courtesy Ministry of the Environment)

Located near the middle of Hokkaidō, the national park is centered on the Daisetsu volcanic group, which includes the highest peak in Hokkaidō, Mount Asahidake (2,291 meters), and encompasses the area known as the “Roof of Hokkaidō,” which includes the magnificent peaks stretching from Mount Tomuraushi to the Tokachi and Ishikari mountain ranges as well as the headwaters of two of Hokkaidō’s great rivers, Ishikarigawa and Tokachigawa.

Those mountain peaks stand around 2,000 meters tall, but have a natural environment equivalent to 3,000-meter mountains in Honshū because of the area’s high latitude. The colors in the vast alpine area are bright and vivid because of the alpine plants that grow there, which include plants native to Daisetsuzan like Oxytropis japonica (locoweed) and Lagotis yesoensis. The vivid colors led the indigenous Ainu people to call this area Kamuy Mintara, meaning “playground of the gods.”

The park is also a treasure trove for rare creatures supported by the local habitat, including the Japanese pika, which is a small mountain-dwelling mammal thought to be an Ice Age relict; the Parnassius eversmanni daisetsuzanus butterfly; and the Salvelinus malma miyabei (Miyabe char) native to Lake Shikaribetsu.

(Date of designation: December 4, 1934. Area: 226,764 ha.)

6. Shikotsu-Tōya National Park

Lake Shikotsu. (Courtesy Chitose municipal government)

Lake Tōya in Winter. (Courtesy Tōyako municipal government)

The park centers on Lake Shikotsu and Lake Toya, and features a landscape composed of volcanoes and volcanic formations of various shapes, including Mount Usu, Mount Yōtei, and Mount Tarumae. The park can truly be described as a “living volcano museum” because of the variety of volcanic activity in the area, which includes many hot springs and sulfur springs. Also located in the park is the second-deepest lake in Japan, Lake Shikotsu, known for being the northernmost lake that does not freeze over in winter.

The park is accessible from central Sapporo and New Chitose Airport, and some of Hokkaidō’s most popular hot spring resorts are located in the area, including Noboribetsu, Lake Tōya, and Jōzankei.

(Date of designation: May 16, 1949. Area: 99,473ha.)

Note that Japan’s national parks also include a lot of private land and many residents. The parks are managed to preserve nature while allowing for coexistence with other activities.

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo: The Shiretoko Mountain Range in summer. © Shiretoko Nature Foundation.)