After Sekigahara: Reshaping Japan

History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Betting on Clan Survival

See the first and second parts of this three-part series: “Ieyasu’s Ambition: The Road to Sekigahara” and “The Battle of Sekigahara: A Fight for the Future of Japan.”

On October 21, 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu and the eastern army won victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in a matter of a few hours, securing Ieyasu’s control over Japan. However, the outcome was not clear from the start, so for the country’s daimyō, choosing whether to support him or join the western army in opposing him was a gamble on the future of their clans.

There must have been earnest discussions in every one of these clans, as defeat would be irrevocable. There were many cases of arguments and splits within families and among vassals due to refusal to compromise on personal beliefs.

One famous example was in the Sanada clan, whose leader Masayuki joined Ieyasu’s planned punitive expedition to the Aizu domain (now Fukushima Prefecture) earlier in 1600. He then received a secret message from Ishida Mitsunari, calling on him to join forces planning to oppose Ieyasu, and discussed it with his eldest son Nobuyuki and his second son Yukimura.

Masayuki and Mitsunari were connected, as both were married to daughters of Uda Yoritada, while Yukimura was married to the daughter of Ōtani Yoshitsugu, a Mitsunari ally. On the other hand, Nobuyuki’s wife was Ieyasu’s adopted daughter Komatsuhime. Thus, Masayuki and Yukimura joined the western army, while Nobuyuki fought on the side of the eastern army, ensuring that the Sanada clan would survive, whichever side was defeated. After the battle, Nobuyuki pleaded for the life of his father and brother, who went into exile.

The Zenmyōshōin temple in Kudoyama, Wakayama Prefecture. It is said to have been the place of exile for Sanada Masayuki and Nobushige after the Battle of Sekigahara, and is also known as Sanada-an. (© Pixta)

While clans who allied with the eastern army thereby preserved their territory, there were some mystifying actions, perhaps as daimyō had family preservation on their mind. One example comes with the Maeda clan of the Kaga domain (now Ishikawa Prefecture).

Before the Battle of Sekigahara, Maeda Toshinaga, who had recently succeeded to his father Toshiie, sent his mother to Ieyasu’s Edo (now Tokyo) as a hostage, fearful of the other man’s power. This also indicated that Toshinaga would fight on Ieyasu’s side.

However, Toshinaga’s younger brother Toshimasa switched sides from the eastern to the western army, after fighting for Ieyasu in an initial skirmish. There are a number of theories as to his reason for doing so, such as that he received a message from Mitsunari or that his wife was a hostage in Osaka, controlled by the western army, but it is possible that it was a plan decided within the Maeda clan, just in case Ieyasu did not emerge victorious.

After the battle, Toshimasa had his territory taken away, but fervent apologies from Toshinaga saved him from the death sentence, and he lived out the rest of his life in Kyoto. His territory was all given to Toshinaga, so it stayed within the clan. Toshinaga also later gave land to Toshimasa’s son Naoyuki.

In the Kuki clan, based in Shima province (now Mie Prefecture) and famed for its navy, the leader Yoshitaka joined the western army and holed up in Toba Castle. With Ieyasu’s blessing, his son Moritaka surrounded the fortress. This was a clash within the clan, but there was no serious fighting until news of Ieyasu’s victory at Sekigahara led Yoshitaka to flee and ultimately commit seppuku.

Moritaka had meanwhile actively been attacking nearby members of the western army, impressing Ieyasu. As a result of Yoshitaka’s assumption of responsibility through seppuku and Moritaka’s achievements in battle, the Kuki clan considerably increased its territory.

Mitsunari in Defeat

After the collapse of the western army, its leader Mitsunari took flight to Mount Ibuki, ultimately leaving his vassals and moving alone. However, during extensive searches for remnants of the defeated side, he was captured by former friend Tanaka Yoshimasa and brought before Ieyasu in Ōtsu.

A representation of Ishida Mitsunari in a picture scroll showing the Battle of Sekigahara. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

According to the eighteenth-century account Jōzan kidan (Writings of Jōzan), Mitsunari’s guard Honda Masazumi said his disgrace was deserved, as he had started a senseless conflict when he should have guided Toyotomi Hideyori, the young son of former Japanese leader Hideyoshi, to build a world of peace. Mitsunari responded by saying he thought it was right to overthrow the Tokugawa clan, but he had lost a battle that he should have won through the actions of traitors. Even the great warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune was killed when his luck ran out. “I was defeated by heaven’s will,” he said, showing no regret.

Masazumi went on to say that a wise leader would have been able to judge who was on his side, and criticized him for not committing seppuku. Angered, Mitsunari replied, “You know nothing of military strategy. Only worthless samurai cut open their stomachs, so they won’t be killed by someone else. When Minamoto no Yoritomo [who later became shōgun] lost the Battle of Ishibashiyama, he hid himself in a hollow tree trunk. You can’t imagine his feelings then, and you talk about what leaders should do with no understanding of the matter. I have nothing more to say.” After that, he did not speak again.

However, he later came face to face with Ieyasu, who told him, “This kind of thing has happened since ancient times, and there is no need to be ashamed.” His mood restored, Mitsunari said, “It was heaven’s will. Now cut my head off at once.” Ieyasu praised him as having the caliber of a leader.

When Mitsunari was taken out of the stronghold, Kobayakawa Hideaki, who had started with the western army but turned on his allies during the battle, was there to watch from personal curiosity. Mitsunari cursed Hideaki for his betrayal; the latter found no words to respond, and is said to have made a dejected exit.

After being paraded with other prisoners around Osaka and Sakai, Mitsunari was taken to Kyoto. On November 6, he was further carried around that city before heading toward the Rokujōgawara execution grounds. A story goes that on the way, he was thirsty so asked a guard for water. The man offered him a dried persimmon, but Mitsunari refused it as bad for his health. The guard laughed at this comment from a man on his way to be beheaded. Mitsunari responded by saying that it was important to preserve his health and try to achieve what he could until the last moment. As this story does not appear until later records, however, it is not thought to be true.

Mitsunari’s head was displayed on the Sanjō Ōhashi bridge until the head priest of the Daitokuji temple requested that it be taken down. The defeated Mitsunari is said to have been buried at the Sangen’in temple in Kyoto.

Sangen’in in Kyoto is known as the location of Ishida Mitsunari’s grave. Usually, it is not open to the public; in February 2023 it was opened for the first time in around 50 years, but visitors could not see Mitsunari’s grave. (©©Pixta)

Territorial Rewards and Punishments

Mitsunari was just one of a few daimyō in the western army who were executed, and even including those who committed seppuku, the total comes to less than 10. However, those who did not promise Ieyasu in advance that they would change sides generally either had their domains abolished or their territory greatly reduced.

Some 88 clans suffered kaieki, or loss of rank, after the battle. While Mōri Terumoto, the western army commander, escaped this fate, his territory was reduced from eight to just two provinces, while Uesugi Kagekatsu, who defied Ieyasu shortly before the battle, had his lands cut down from 1.2 million koku in Aizu (now Fukushima Prefecture) to 300,000 koku in Yonezawa (now Yamagata Prefecture) (a koku is a unit equivalent to around 180 liters of rice). Ieyasu confiscated 6.3 million koku from enemy leaders, or around a third of the total production in the realm.

Satake Yoshinobu of Hitachi Province (now Ibaraki Prefecture) did not participate in the Battle of Sekigahara, instead waiting to see who would emerge victorious. Ieyasu sent him to what is now Akita Prefecture, where his land was reduced to one third of its previous koku.

The Tokugawa clan increased its own territory from 2.5 million to 4 million koku, taking control of towns and mines owned by the Toyotomi clan. This did not mean that Ieyasu could do exactly as he pleased, however, as is evident from the two and a half years he required before becoming shogun and instigating his shogunate in Edo.

This was because his son Hidetada’s army, representing the main Tokugawa force, was late to the Battle of Sekigahara, which meant tozama daimyō connected to the Toyotomi clan, although fighting on the side of the eastern army, monopolized the military exploits. By contrast with the word fudai for long-standing vassals, tozama was a term covering both those lords who allied with Ieyasu before the battle and those who submitted after it was over.

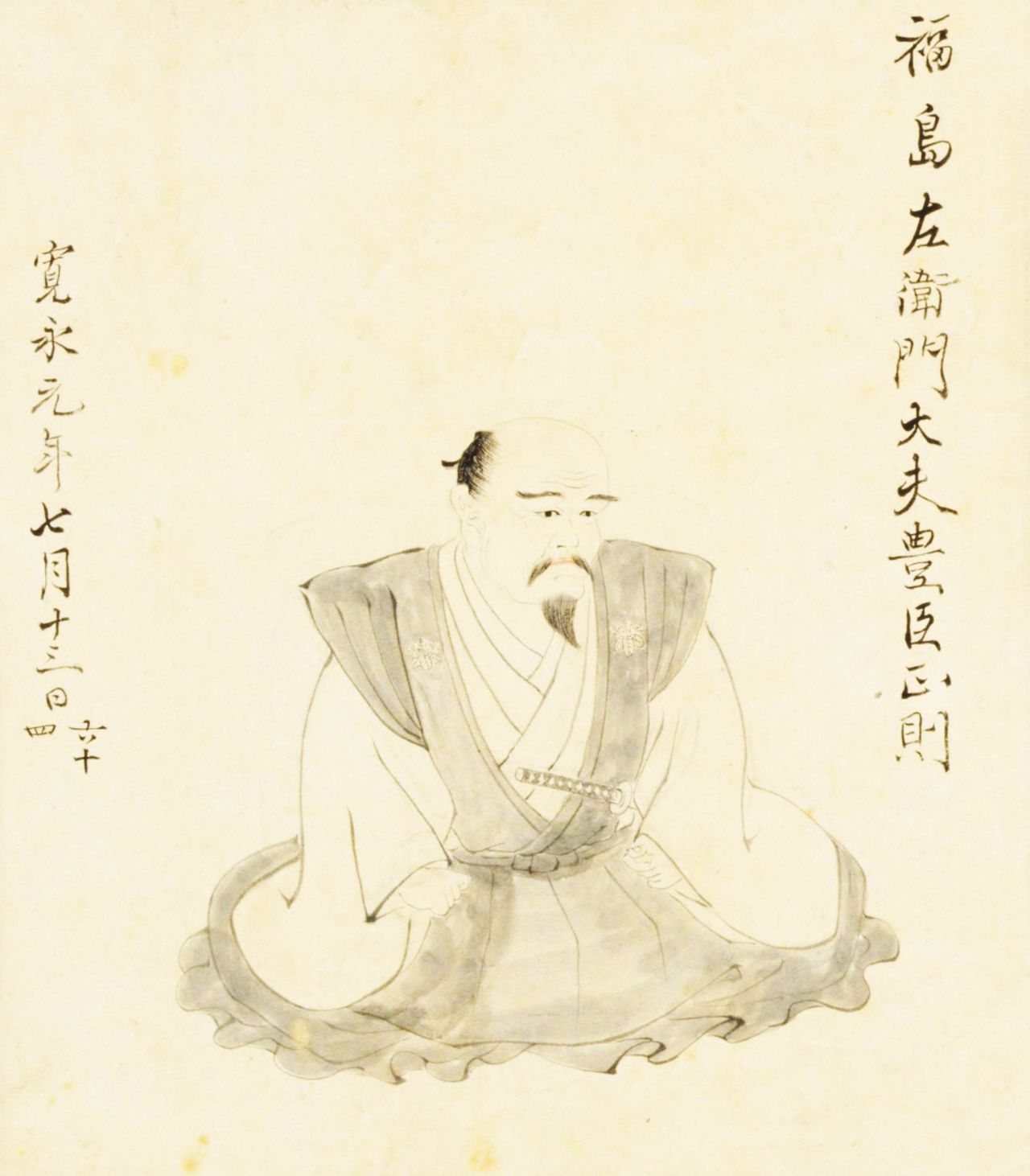

Ieyasu had to increase the territory of such new allies as Fukushima Masanori, Kuroda Nagamasa, and Yamanouchi Kazutoyo. Masanori’s koku rose from 290,000 to 498,000 in Aki and Bingo provinces (now Hiroshima Prefecture), while Nagamasa’s were boosted from 180,000 to 520,000 in Chikuzen province (now Fukuoka Prefecture). Kazutoyo was made lord of Tosa province (now Kōchi Prefecture), lifting his koku from 50,000 to 200,000.

A nineteenth-century portrait of Fukushima Masanori by Kurihara Nobumitsu. Although a retainer of the Toyotomi clan, with the death of Hideyoshi he became an ally of Ieyasu and fought in the front line at the Battle of Sekigahara. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Even while he made these increases, Ieyasu tended to keep the tozama at a distance from the Tokugawa heartland of Edo and its surrounding Kantō region, as well as the major cities of Osaka and Kyoto, rather awarding them territory in the west of the country, such as in Kyūshū and Shikoku. At the same time, he placed small domains with fudai daimyō and areas of shogunate territory in the west, and installed his son-in-law Ikeda Terumasa at Himeji as a check on Hideyori.

At Sekigahara, Terumasa stood off against enemy troops on the slopes of Nangūsan and did not become involved in any major engagements, but was nonetheless rewarded with Harima province (now Hyōgo Prefecture) with territory of 521,000 koku, a domain more than three times larger than his previous holdings.

As for Hidetada, who was late to the Battle of Sekigahara, it is a later invention that Ieyasu was too furious to meet him for some time, before choosing him again as his successor. This would have been a considerable blow to Hidetada’s prestige.

This concludes my series on the Battle of Sekigahara. It has often been said that many daimyō expected the fighting over control of Japan to continue for at least several months, and did not imagine that it would be decided instead in just a few hours. Ieyasu himself may have been the most surprised of all.

(Originally published in Japanese on October 28, 2023. Banner image: Folding screen showing the Battle of Sekigahara. This is the left-hand screen of a pair created in the Edo period [1603–1868]. It depicts the battlefield from the south, with the eastern army pushing forward. Courtesy Watanabe Museum of Art in Tottori, Tottori Prefecture.)