Tea and Aesthetics: Kawabata Yasunari’s Nobel Lecture

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A First for Japan

On October 17, 1968, Kawabata Yasunari was chosen by the Swedish Academy as the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature “for his narrative mastery, which with great sensibility expresses the essence of the Japanese mind.” The news of the first Japanese writer to receive the prize made headlines in his home country and across the world.

More than half a century has passed since then. After 50 years, documents concerning the prize selection process are made public, and with some further research, the path to each writer’s award becomes apparent. Such studies show that the selectors turned to Japanese literature as the result of deciding to correct the imbalance favoring Western writers. Tanizaki Jun’ichirō and Nishiwaki Junzaburō were the first Japanese candidates in 1958, and Tanizaki was on the final shortlist in 1960, while Mishima Yukio reached the shortlist in 1966, and both he and Kawabata were on it in 1967. Kawabata’s award came not only for his literature but was also an expression of international recognition of Japanese literature.

Later, Ōe Kenzaburō won the prize in 1994, while more recently Murakami Haruki’s name has been repeatedly suggested as a possible candidate. Tawada Yōko, who writes in both Japanese and German, is also seen as a strong contender. Writers from outside the West and those who operate beyond the borders of national literatures are coming under the spotlight. The contours of the literary world have undergone a great transformation in the past 50 years.

In an NHK special program, Kawabata said that his winning of the award was thanks to his translator, Edward Seidensticker. As the selectors would not have been able to read the original Japanese, without excellent translations he could never have won. Comparative literature scholar David Damrosch has said that world literature is “writing that gains in translation.” Through translation, Kawabata’s work gained new life, showing the way forward to today’s world literature that finds readers by crossing linguistic borders.

Immersion in Traditional Culture

Kawabata left Japan on December 3 to take part in the award ceremony in Stockholm. In the two months following the announcement that he had won the prize, he took time to reconsider the connections between his writing and traditional Japanese culture and art.

One way he did this was by participating in the Kōetsukai. This is a tea ceremony event honoring the artist Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637), held every year from November 11 to 13 at the Kyoto temple Kōetsuji. Kawabata wrote in the essay “Ibaraki-shi de” (In Ibaraki) about his appreciation of the historic tea utensils while in the former capital during the season of autumn leaves.

Kawabata had long had an interest in tea culture, and one of his most notable postwar works Senbazuru (trans. Thousand Cranes) depicts the vulgarized relations of people in the tea world. When the International PEN conference was held in Tokyo in 1957, as the chairman of Japan’s own PEN Club, he also won the cooperation of the Urasenke school to hold a tea ceremony for the visiting literati. Amid a hectic schedule, with his historic Nobel acceptance looming, his effort to take part in the Kōetsukai could be viewed as his sense that he had gained an opportunity to immerse himself in Japan’s traditional culture.

After this, on November 14, Kawabata headed to Nagoya to meet with the potter Arakawa Toyozō, known for his discovery of shards of Shino pottery dating back to the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568–1603) and his efforts to reproduce their style himself. In Thousand Cranes, Kawabata’s depiction of a Shino chawan (tea bowl) and its texture and coloring are overlaid with the image of an alluring woman. This had been a meeting of two artists deeply impacted by the Shino works.

On this occasion, Arakawa displayed Tsuruzu shitae wakakan (Scroll with Waka and Underpainting of Cranes), which he had acquired in 1960. Some 14 meters in length, the work features a painting by Tawaraya Sōtatsu of a large group of cranes using kingindei (a mixture of gold and silver foil and glue) and scattered calligraphy by Hon’ami Kōetsu of waka by the group of classic poets known as the Thirty-Six Poetic Immortals. Today, it is in the Kyoto National Museum, but at that time it was owned by Arakawa. As a way of celebrating Kawabata’s award, he showed the Thousand Cranes author this treasured artwork covered with cranes.

The title of Kawabata’s novel derives from the pattern of the furoshiki cloth the character Yukiko carries to the tea ceremony. The cranes symbolize the beauty of her figure, temperament, and deportment. Here, there is a connection with the development of the character Kikuko, who appears in another of the author’s major postwar novels, Yama no oto (trans. The Sound of the Mountain). It is not difficult to imagine that, on seeing the artwork with its senbazuru (thousand cranes) design, Kawabata—himself an art collector—recalled in vivid detail the Rinpa school running from Kōetsu and Sōtatsu through to the brothers Ogata Kōrin and Kenzan.

Kawabata writes in a letter to the artist Higashiyama Kaii of being stunned by his encounter with Arakawa’s artwork. For him, the meeting with Arakawa must have reminded him of the relations between Thousand Cranes, Shino pottery, and the Rinpa school. His participation in the Kōetsukai and discussion with Arakawa made him realize once more the deep links between his own works and Japan’s traditional culture and art.

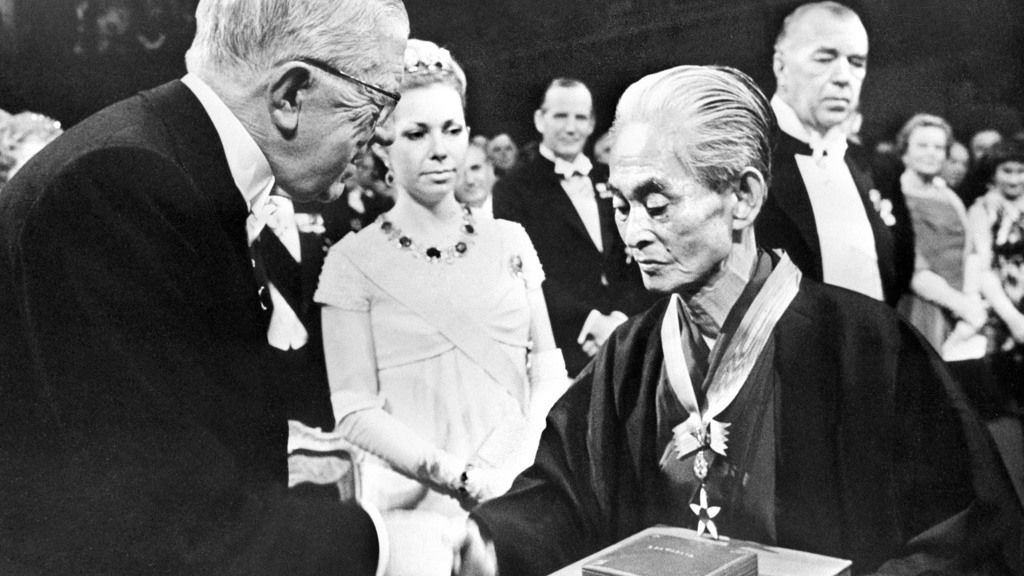

The Tea Ceremony and the Nobel Lecture

On December 10, Kawabata, dressed in a haori and hakama, received the Nobel Prize medal and diploma at the award ceremony. The diploma was decorated with a senbazuru design. Two days later, he gave a commemorative lecture entitled “Utsukushii Nihon no watashi: Sono josetsu” (trans. “Japan, the Beautiful and Myself”). He spoke in Japanese, and Seidensticker simultaneously interpreted into English. However, Seidensticker recalled that Kawabata split the royalties with him fifty-fifty for a book containing the original speech and English translation. This demonstrates the respect Kawabata showed to his translator.

In his lecture, Kawabata quotes from classical Japanese literature and notable religious figures, while discussing the aesthetic sense in the nation’s culture and bringing to the surface the essential nature of his own writing in relation to that culture. Toward the opening, he recites a waka by the Buddhist priest Myōe (1173-1232): “Bright, bright, and bright, bright, bright, and bright, bright. / Bright and bright, bright, and bright, bright moon.” He also includes the accounts of the origins of a poem written on the night of the twelfth day of the twelfth month of the first year of the Gennin era (equivalent to January 1225). It was an exquisite dramatic effect to choose a waka with that date to match with December 12, the day of the lecture.

Kawabata had the tea ceremony in mind as he wrote his speech. Within it, he introduces how a confined tearoom contains boundless space, how it is adorned with a single bud of a camellia or peony; and he describes the tea bowls moistened to give them their own soft glow.

Tea practitioners see encounters during tea ceremonies as ichigo ichie, happening once and never to be repeated, and make elaborate preparations to heighten the pleasure of the event. They decorate the room with hanging scrolls with penmanship by Zen priests or fragments from picture scrolls and poems and take care to select tea utensils that match the season and occasion, arranging them on the floor for guests. In the same way, Kawabata studded his speech with various episodes and classic poems, as well as providing an introduction to the world of tea.

In fact, Sweden has a deep connection with the tea ceremony. In 1935, at the strong urging of the Japanologist Ida Trotzig—who was greatly interested in the tea ceremony and wrote a book on the subject—the paper magnate Fujiwara Ginjirō donated the teahouse Zuikitei. Destroyed by fire in 1969, it was rebuilt in 1990, and can be visited today at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm. Thus, it was wholly fitting that Kawabata talked about the aesthetic aspects of the tea ceremony in this city as he delivered his lecture to express his appreciation for the award he had received.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Kawabata Yasunari receives the Nobel Prize from King Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden in Stockholm on December 10, 1968. © Jiji.)