Saruhashi Katsuko: A Pioneering Scientist Shedding Light on the Dangers of Radiation

Science Society History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

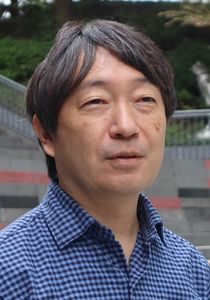

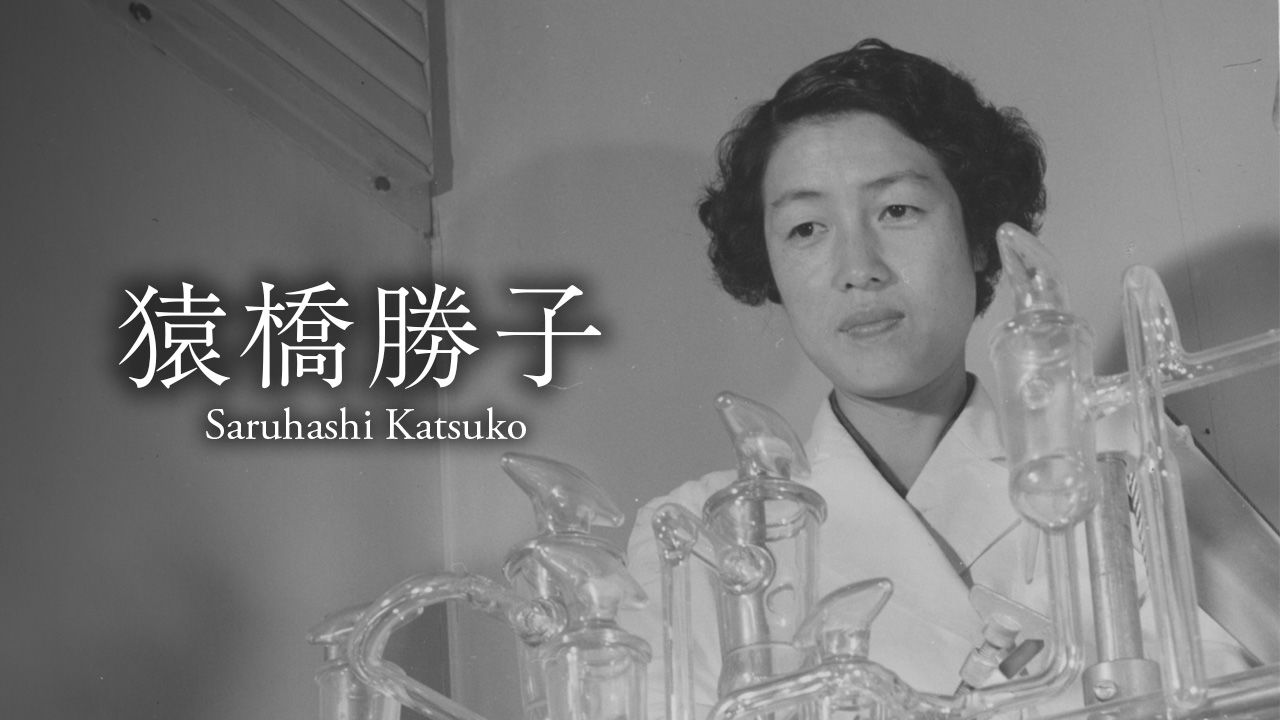

The Saruhashi Prize is familiar to many as a prestigious honor awarded to Japanese women for outstanding work in the natural sciences. Yet too few people know about the historic achievements of the award’s founder, the geochemist Saruhashi Katsuko (1920–2007). The writer Iyohara Shin, author of a recently published biographical novel about the pioneering woman scientist, shared some of the knowledge and insights gained from a decade of research.

A Story Waiting to Be Told

Iyohara, who has an extensive background in earth and planetary physics, first took an interest in Saruhashi about 10 years ago, when he learned of her achievements from a member of the Saruhashi Prize selection committee, whom he had studied under as a graduate student. His former mentor told him that Saruhashi was “an amazing person” who had taken her methodology to the United States and triumphed over the skepticism of distinguished American scientists with her groundbreaking analysis of radioactive marine pollution.

“I had heard of Saruhashi as a researcher in the area of geochemistry, but I didn’t know what she had actually done,” confesses Iyohara. “As I learned more, I realized she would make an excellent subject for a biographical novel, and I decided I had to tell her story.”

Unable to locate any living person who had known Saruhashi in her youth, Iyohara delved deeply into patchy prewar and wartime records. Over the course of a decade, he assiduously reconstructed the historical context and his subject’s viewpoint to produce Sui-u no hito (Like Rain on Green Leaves), a work of biographical fiction published in July 2025.

Making of a Scientist

Saruhashi Katsuko was born in 1920 in Tokyo, the daughter of an electrical engineer. She was a frail child, and by her own account she grew up in a loving and indulgent environment. While still in elementary school, she would gaze out the window on rainy days and wonder, “What is rain? Why does it rain?” This scientific curiosity was to shape her life and career.

After elementary school, Saruhashi enrolled in a girls’ high school, a five-year institution of secondary education established under the prewar school system. After that, there were just two options for women seeking a higher education: women’s normal schools, designed to train female teachers, and a small number of private professional schools. Upon graduating from high school, Saruhashi initially went to work for a life insurance firm, but she dreamed of studying medicine. She idolized Yoshioka Yayoi, the pioneering doctor who had founded Tokyo Women’s Medical School (the forerunner of Tokyo Women’s Medical University), and hoped to follow in her footsteps. With her family’s approval, she quit her job to devote herself to preparing for the school’s rigorous entrance examination, which she passed in 1941, securing an interview with Yoshioka.

Saruhashi later wrote of that episode in an autobiographical essay. Asked why she had applied, Saruhashi replied, “I want to study very hard and become a great physician like you, Dr. Yoshioka.” To this, Yoshioka laughed heartily and said, “Don’t be silly. You really think it’s that easy to become someone like me?” Shocked and disillusioned, Saruhashi abandoned her dream of becoming a doctor. Instead, she applied to the Imperial Women’s College of Science, established the same year, and entered its first graduating class. The Imperial Women’s College of Science, later to become the Tōhō University Faculty of Science, was the first professional school in Japan where women could study chemistry and physics.

In her second year, Saruhashi was assigned to an internship with earth scientist Miyake Yasuo at the Central Meteorological Observatory (forerunner of the Japan Meteorological Agency), who became her graduation thesis advisor. The topic he assigned her dealt with polonium, the radioactive element discovered by Marie and Pierre Curie in 1898 (leading to their receipt of the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics). Saruhashi’s study of polonium stood her in good stead later, when she turned her attention to the measurement of radioactivity, and she found an inspiring example in Madame Curie’s life and work.

She also took to heart the words of Pierre Curie, who presciently asked whether humankind was ready to benefit from the discovery of radioactivity, or whether it would ultimately be harmed by that knowledge.

Wartime Research in Hokkaidō

In 1943, as the tide of World War II turned against Japan, the first class of the Imperial Women’s College of Science graduated six months ahead of schedule. Saruhashi immediately went to work at the Central Meteorological Observatory, where she applied herself assiduously to basic research. During those years, however, it was virtually impossible to insulate science from the military and its aims. In 1944, Miyake, Saruhashi, and other observatory staff were enlisted to work with the Imperial Army’s meteorologists on a large-scale fog observation project in Nemuro, Hokkaidō. The purpose was to gather data that could be used both to forecast foggy conditions and to create them artificially. Leading the project was glaciologist Nakaya Ukichirō of Hokkaidō University, known for his work on snowflakes.

“We don’t really know a great deal about this wartime research,” says Iyohara. “I dug through all kinds of records, but in the end I had to use my imagination to fill in the gaps.”

Nor is there any record of what scientists like Nakaya and Miyake felt about their work for the military. On the basis of his extensive background research, however, Iyohara believes that their top priority was keeping young scientists off the battlefield and protecting the foundations of basic research with an eye to the postwar future.

Innovation and US Skepticism

The pivotal historical event shaping Saruhashi’s postwar career was the 1954 Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb detonation, one of a series of thermonuclear weapon design tests carried out by the United States on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. In March that year, a crew of 23 on the Japanese fishing boat Daigo Fukuryū Maru (known in English as Lucky Dragon No. 5) was exposed to nuclear fallout from the detonation. Saruhashi supervised the analysis of a small quantity of white ash brought back by the crew members, one of whom died from radiation sickness. Her analysis determined that the substance, described as “ashes of death,” consisted of radioactive particles of coral.

The tuna fishing boat Daigo Fukuryū Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) on display at the Daigo Fukuryū Maru Exhibition Hall in Tokyo and a bottle containing “ashes of death” collected from the vessel. Photos taken in June 2024. (© Jiji)

Amid ongoing nuclear testing by the United States, the Soviet Union, and other countries, Saruhashi played a leading role in research to measure levels of radioactivity in rain and seawater. Using a new method of analysis that they had developed themselves, Saruhashi and other members of Miyake’s research team determined that the concentration of radioactive substances in Japan’s coastal waters was many times higher than that found off the United States. They concluded that fallout from the Bikini Atoll tests had drifted toward Japan on ocean currents.

These findings were challenged by American scientist Theodore Folsom, also known for his development of methods for tracing ocean contamination by fallout from nuclear testing. Folsom called the Japanese data flawed, believing that it exaggerated the concentrations of radiocesium in Japanese waters. In response, Miyake asked the US Atomic Energy Commission to sponsor a project directly comparing the two analytical techniques. The commission agreed, and in 1962, Miyake sent Saruhashi to the United States by herself, entrusting the entire project to her. At the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of San Diego, Saruhashi faced off against a team led by Folsom, with each side using its own method to precipitate radiocesium from standardized samples. Saruhashi’s technique proved significantly more efficient in recovering cesium, and the accuracy of her assay method was validated. Folsom gave Saruhashi her due, and in 1963 the two jointly published a paper reporting the results of their work.

Impact on Society and Science

“The research conducted by Miyake and Saruhashi was a major force behind the global groundswell of opposition to nuclear testing,” says Iyohara. “Moreover, by proving that radioactive contamination of the waters in the Northwest Pacific was more advanced than the United States had supposed, their work hastened the conclusion of the [1963] Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.”

From left: Saruhashi, (left) and Miyake in Osaka in 1960; Saruhashi at her laboratory at the Meteorological Research Institute in Tokyo in 1965. (Photos courtesy The Association for the Bright Future of Women Scientists)

In addition, he says, “Saruhashi made a significant contribution to science through her study of the ozone layer and her microanalyses of seawater to determine how levels of carbonic substances fluctuate under different conditions.”

Carbonates in seawater are essential to marine life and are a crucial element of the cycle by which the oceans absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide, a key culprit in climate change. In a 1955 paper, Saruhashi published a chart for calculating how factors like temperature and pH affect the levels of carbonic substances in seawater. Oceanologists around the world relied heavily on “Saruhashi’s table” until computers came into widespread use.

Fostering Achievement by Women Scientists

Iyohara’s narrative centers on Saruhashi’s life and career from her youth up through her forties. What emerges from his account is the image of a woman uncompromisingly devoted to the pursuit of scientific truth.

“I imagine some readers might be disappointed by the unglamorous nature of her research activity,” says Iyohara. “But almost all scientific research is a slow, laborious accumulation of mundane observations and analyses. It’s in the moment when that laborious process yields some new truth or insight that scientists experience the deeply satisfying side of research.”

Retiring from the JMA’s Meteorological Research Institute in 1980, Saruhashi used her own resources to fund the Association for the Bright Future of Women Scientists, which awards the annual Saruhashi Prize. The prize, which honors the achievements of women researchers and educators under the age of 50, was established with the aim of recognizing and encouraging women’s contributions to science. It has been awarded to 45 individuals since 1981.

Saruhashi at the award ceremony of the Saruhashi Prize in 1998. (Courtesy The Association for the Bright Future of Women Scientists)

As Iyohara notes, however, all too few Japanese women have followed in Saruhashi’s footsteps.

“In Japan, very few schoolgirls opt for the math and science track to begin with,” he laments. “If Saruhashi could see the situation in Japan today, I think she would be very disappointed by the slow rate of women’s advancement.”

Science and Warfare

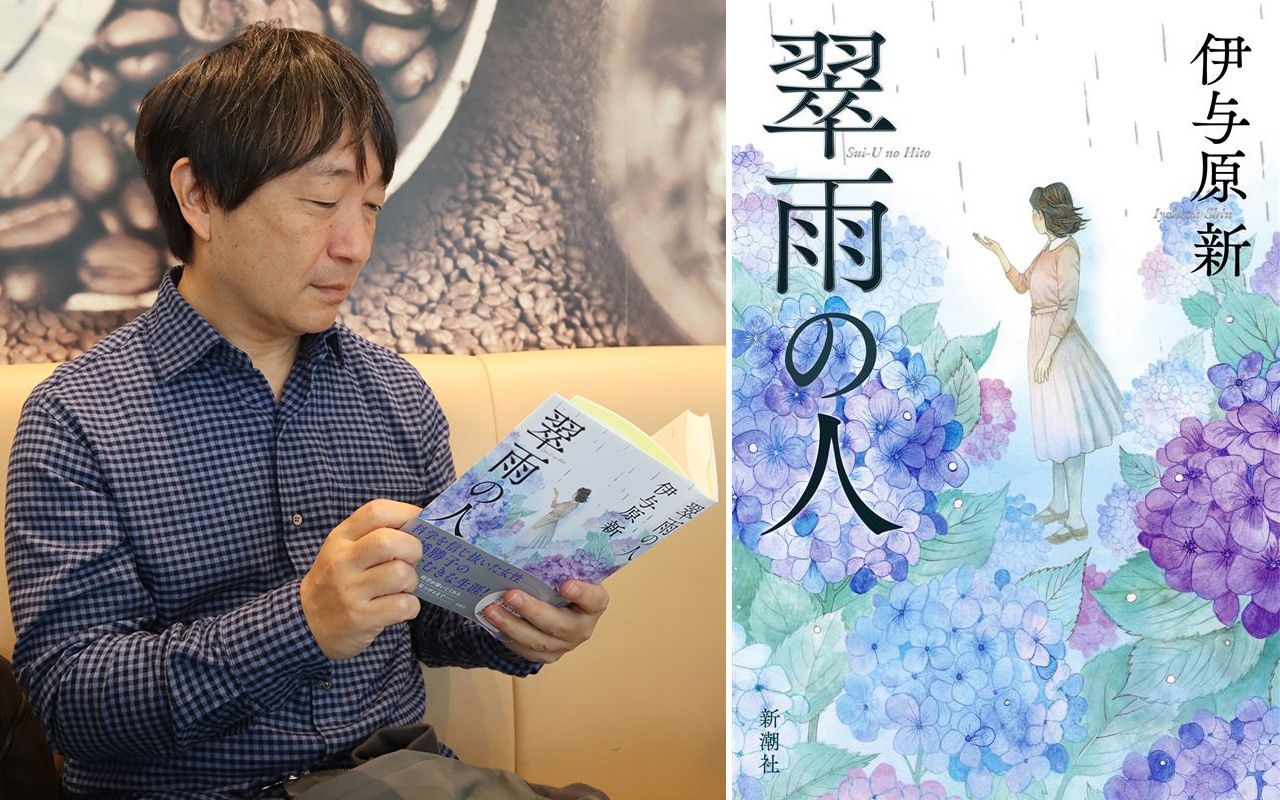

Iyohara Shin and the cover of his book Suiu no hito. (© Nippon.com)

In the course of his research for the book, Iyohara made a number of unexpected discoveries about the history of Japanese science before, during, and after World War II.

“A striking characteristic of Japanese scientists in Saruhashi’s time was their deep determination to contribute to the betterment of society,” says Iyohara. “I was amazed to see such deep commitment among analytical chemists, who united to solve postwar problems like seawater contamination and environmental pollution. Today you rarely see scientists banding together to address social or global issues.”

Iyohara’s work on the book gave him much food for thought about the relationship between science and war. “I’m glad I was able to publish my book in 2025, eighty years after the end of World War II, at a time when the war in Ukraine and other global conflicts are reviving these issues.”

In today’s uncertain international climate, with the use of nuclear weapons reemerging as a real concern, Iyohara’s book is a timely reminder of Saruhashi’s role in alerting the world to the dangers of radioactive fallout.

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com. Banner photo courtesy of The Association for the Bright Future of Women Scientists.)

women nuclear bomb nuclear disarmament nuclear test scientist