Paralympic Athletes, Up Close and Personal

The Strength to Win: Paralympic Powerlifter Nishizaki Tetsuo

Sports Tokyo 2020 Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Bench Pressing for Gold

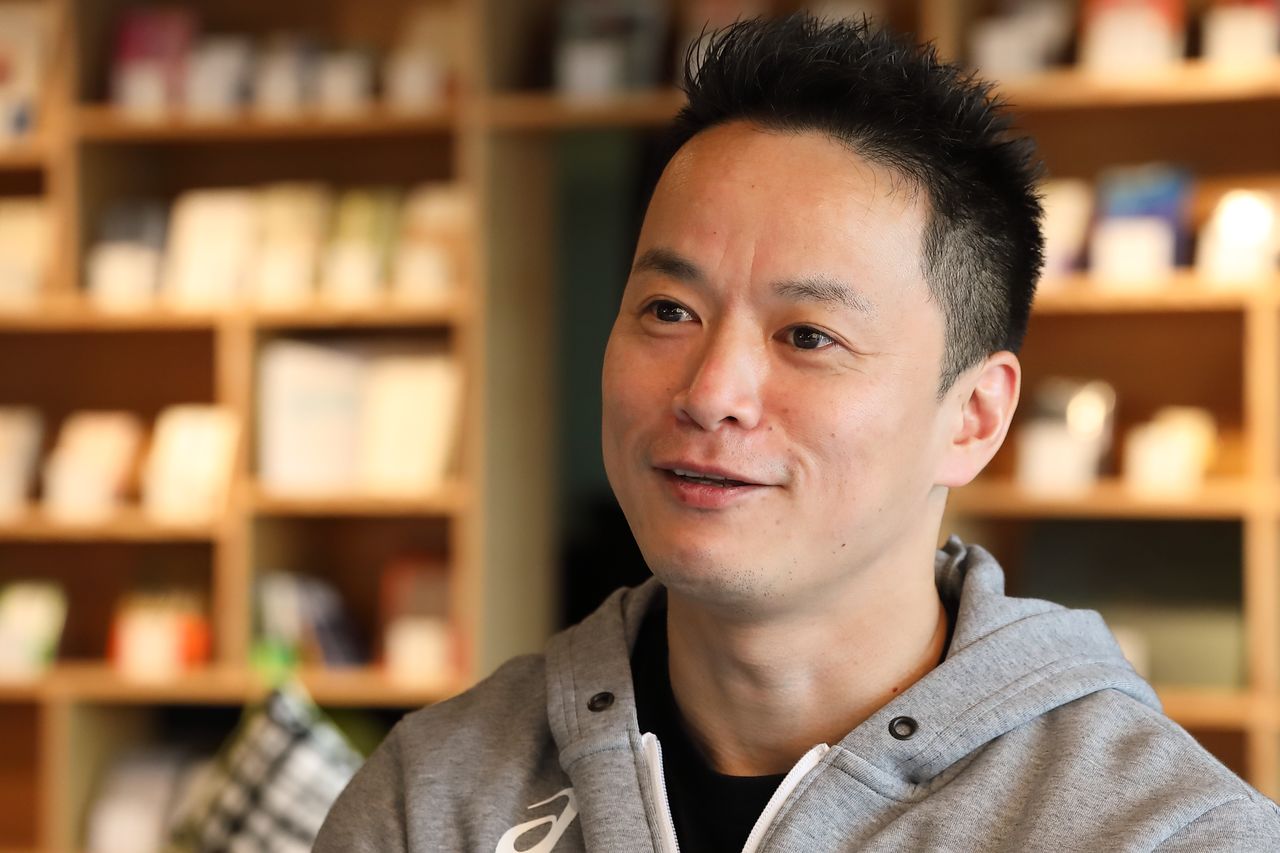

Paralympic powerlifter Nishizaki Tetsuo has an uncanny way of drawing in listeners. Projecting a fresh-faced smile and speaking in an animated way, the Japanese record holder in the 54-kilogram weight division disarms his audience and creates a jocular mood.

Nishizaki is training hard at the bench press, para powerlifting’s single discipline. He is particularly fond of pointing out that in terms of sheer might, nothing separates disabled powerlifters from their able-bodied peers. “In fact,” he exclaims, beaming his trademark grin, “it’s not uncommon for para athletes to notch bigger records.”

Nishizaki inside his company’s training room.

Such a case happened at the 2016 Rio Paralympics when Iran’s Siamand Rahman, competing in the over 107-kilogram class, won gold with his record-setting bench press of 310 kilograms. “That’s more than 20 kilograms over the world record for able-bodied athletes,” Nishizaki declares with a hearty laugh.

The difference in the 59-kilogram weight class, one division above where Nishizaki competes, is even greater. As recently as June 2018, the men’s para powerlifting record stood at 210.5 kilograms, compared to the able-bodied best of 171 kilograms, a gap of over 40 kilograms.(*1)

Nishizaki knows there are various theories floating about, including the assumption that para athletes’ reliance on wheelchairs gives them an advantage in upper-body strength. Instead of pushing half-baked ideas about the differences between disabled and able-bodied competitors, though, he is content to accept that some things have yet to be explained, remarking wryly that “the human body still hides many mysteries.”

Power Gap

Paralympic powerlifting is a straightforward test of upper-body strength. Powerlifting competitions for able-bodied athletes include squat and deadlift events too, but Paralympians do just one event: the bench press. Athletes with physical impairments that affect their lower limbs or hips, or are of short stature, are divided into 10 classes based on body weight for each gender. During a lift, competitors lay flat with their head, shoulders, and buttocks touching the bench, lower the bar to their chest in a controlled manner, and then power it back up to arm’s length and locked elbows. Athletes have three lift attempts, and the winner is the one who lifts the heaviest weight.

In the Paralympics there are a maximum of 10 berths for each weight class. To qualify for the games, an athlete must be ranked in the top eight globally or receive one of two slots allocated under the bipartite invitation system. In 2016 the Japanese team at Rio consisted of the trio of Nishizaki, Miura Hiroshi in the 49-kilogram division, and Ōdō Hideki in the 88-kilogram division. Miura and Ōdō finished eighth and fifth, respectively, but Nishizaki failed each of his three attempts and did not place.

Nishizaki says he was devastated by the result; a disappointment made all the more bitter by the fact that he was lucky to be competing in the first place. “I was ranked eleventh and didn’t think I would be going. But then one of the athletes in the bipartite invitation slots was removed, and I slipped in just under the wire.”

He blames nerves and poor strategy for his meager performance. Although he had previously set the Japanese record with a lift of 136 kilograms, he decided to play it safe at his first Paralympics and started at 127 kilograms. This proved to be his downfall. Before he knew it his three attempts were up and he was out of the competition without notching a single lift. “Normally that amount is a piece of cake,” he says ruefully. “But I let the atmosphere get the better of me.”

A Matter of Seconds

To an unexperienced person, the bench press may seem as simple as lowering and raising the bar. But Nishizaki explains that the sport demands a mixture of strength and balance. “It’s critical to keep the bar from drifting to the right or left. You have to focus intensely so that all the tendons and muscle fibers in your back, chest, shoulders, and arms fire in perfect harmony.”

Nishizaki at the sixteenth All-Japan Para Powerlifting Championships in Tokyo in January 2016. (© Takemi Shūgo)

Nishizaki says that even though he has fine-tuned his mind and body over years of competing, he knows that skill alone is not enough to come out on top. A lift takes just three seconds to complete, but there are countless factors leading up to it that affect the outcome, including physical condition and atmosphere at the venue. “Each competition is different, and ideally I want to be able to adjust my performance to match any circumstance.” He admits that he has yet to perfect his strategy, but remains hopeful of coming up with a winning formula by the 2020 Paralympics in Tokyo.

Surviving Disaster

Nishizaki was born in Tenkawa, Nara Prefecture, the youngest of three children. He grew up playing sports, first baseball in elementary school and junior high school and then wrestling in high school. He even won a regional championship title with his prowess on the mat, but he confesses he does not have the temperament for one-on-one sports. “You constantly have to search for your opponent’s weakness,” he explains, “and once you spot it, go in for the kill.”

After graduating from high school, Nishizaki began working for a transportation company. In 2001 he was driving a 10-ton truck on the expressway when he rolled the vehicle. The force of the accident threw him from the cab, sparing him from being crushed in the wreckage but still leaving him seriously injured. When he woke up in the hospital he found his wife, family, and work colleagues standing around his bedside. Much to the surprise of those present, though, his first thoughts were about the trouble he had caused his employer and he inadvertently blurted out an apology to the owner of the company, who was among the visitors. “My boss had spent the better half of a year figuring out whether to buy the truck,” explains Nishizaki. “I was devastated for ruining such an important investment.”

The doctors gave Nishizaki little hope of walking again. “I’ll never forget that moment,” he reflects. “It was my birthday and here I was being told that I would have to spend the rest of my life in a wheelchair. I was so scared that I cried nonstop for a week.”

Family First

Once out of the hospital, though, Nishizaki quickly got to work rebuilding his life. Unable to return to truck driving, he studied for and passed the Osaka municipal civil servant exam. Along with his new career, he also took up wheelchair racing, competing in the 400-meter sprint. He says it was a struggle at first to accept his new way of life. “It bothered me how some people looked at me with pity. Racing helped me rebuild my self-confidence, and I gradually grew accustomed to life in a wheelchair.”

A talented racer, he tried out for the Japanese Paralympic squad, but just missed out qualifying for the 2008 Games in Beijing. Although disappointed with his failure, his spirits soared when shortly afterward he and his wife welcomed their daughter. Faced with the challenge of balancing work, training, and his new family, Nishizaki eventually decided to retire from wheelchair racing. “I finished work at six and then went to practice, not returning home most nights until around ten. It got to be too much. I decided to give up on my goal of qualifying for London and spend more time with my daughter.”

A New Challenge

Nishizaki enjoyed having more time for family, but Tokyo’s selection as the host city of the 2020 Paralympics compelled him to return to competitive sports. With the full support of his loved ones, he took up powerlifting, a discipline he was familiar with from having done bench press as part of his earlier training regimen. In 2014, he secured a position as an event designer at his employer, the architectural firm Nomura, with the help of the Japanese Olympic Committee. The job not only offered a new career path, but provided a gym to train and support for his athletic activities.

“I’m blessed to be in a position where I can concentrate just on training,” says Nishizaki, adding with a chuckle that “my only worry is that I’ll get too comfortable and lose my competitive edge.” The words of a fellow para athlete help him to stay focused, though. “When I heard the phrase ‘expectations are pressure, but support is strength’ it really resonated with me. It made me realize how fortunate I am to have so many people cheering me on.”

As Nishizaki prepares for the Tokyo Games, his growing number of fans across Japan will be rooting for another record-setting performance.

Nishizaki trains at Nomura’s Tokyo headquarters. The firm installed a bench press at its Tokyo and Osaka offices.

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview photos by Hanai Tomoko. Banner photo: Nishizaki at the sixteenth All-Japan Para Powerlifting Championships in Tokyo in January 2016. © Takemi Shūgo.)

(*1) ^ In November 2018, the Russian lifter Sergey Fedosienko lifted 205.5 kg at the World Open Powerlifting Championships in Halmstad, Sweden, closing this gap considerably.—Ed.