Paralympic Athletes, Up Close and Personal

Table Tennis Player Doi Kentarō Rises to the Paralympic Challenge

People Society Tokyo 2020- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

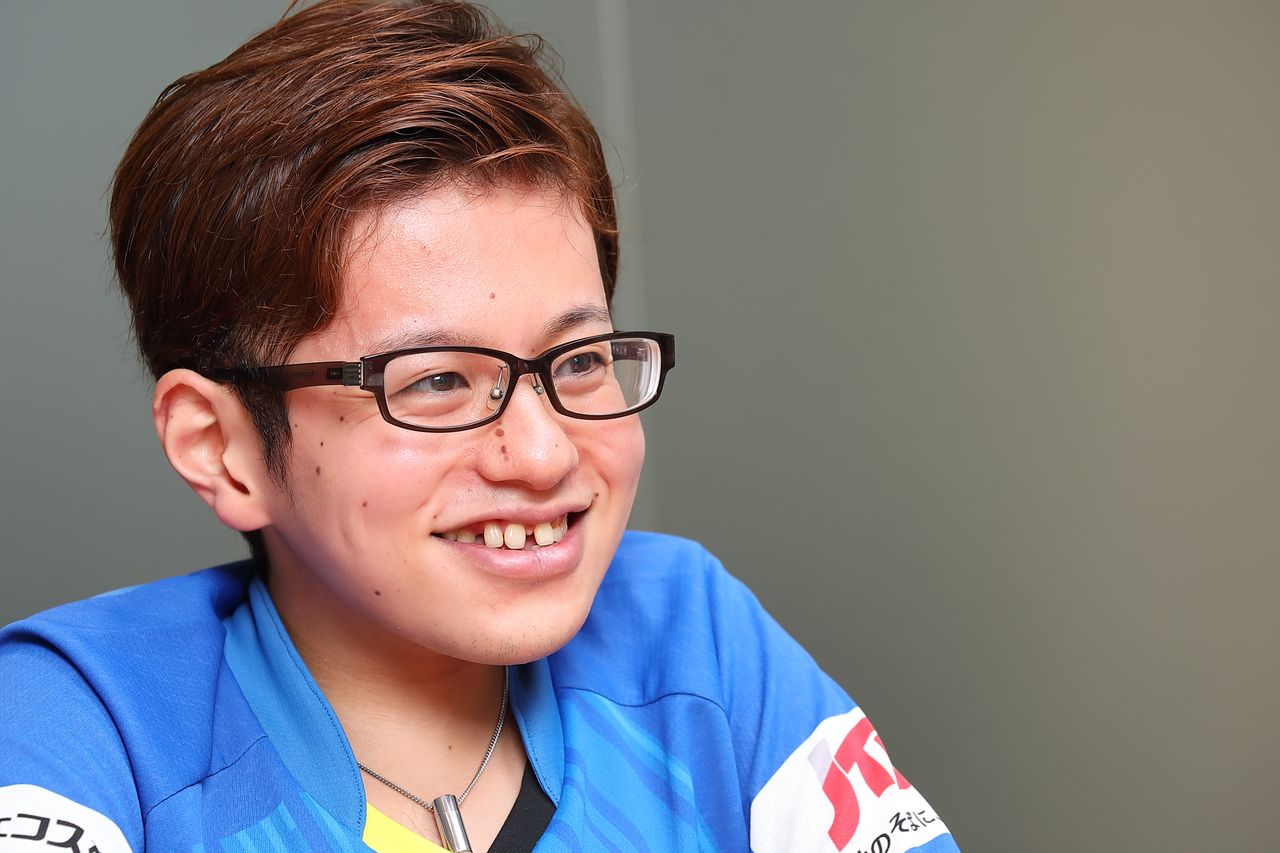

Speaking with para table tennis player Doi Kentarō is a high-paced activity. His intelligence and mental toughness are immediately apparent in the way he snappily answers questions and wryly smiles when giving a coy reply. “I have a bit of a twisted personality,” he jests, clearly enjoying the attention.

Petite in stature, he is one of Japan’s rising stars in the sport. In August he captured individual bronze in the class 5 sitting category and was part of the Japanese team gold at the Para Table Tennis Bangkok Open.

Para table tennis rules, scoring, and equipment are almost identical to the able-bodied variety. Players compete in either wheelchair or standing classes and are further divided into five categories, 1 to 5 for sitting and 6 to 10 for standing, according to functional ability. Doi has full function of his arms and hands, putting him in class 5, a division dominated by fast, heavy-hitting players. Although smaller than many competitors, Doi makes up for his deficit in power with a wicked spin shot and pinpoint accuracy that frustrates opponents.

Twins with the Same Condition

Doi was born in 1996 in Fujinomiya, a small city at the base of Mount Fuji in Shizuoka Prefecture. A twin, he and his brother Kōtarō were diagnosed as babies with osteogenesis imperfecta, a rare genetic disorder also known as brittle bone disease. Doi says their frail condition meant something as mundane as a diaper change could result in a fracture. “One of us was always hurt and bawling our head off,” he explains. “It was really tough for my folks because they were always looking after us.”

Walking was difficult, so the boys grew up using wheelchairs to get around. However, injuries happened even with precautions. “By the time I reached high school I had notched over thirty breaks,” Doi chuckles. “I was always sporting a cast on some part of my body.”

He recalls with a wry smile an incident involving a broken femur, an injury that required Doi to be fitted with a cast that extended from his waist to his toes. After spending all day at the doctor’s, his parents accidentally bumped his foot on the door while trying to carry him into the house, fracturing his toe and requiring the family to turn around and head back to the hospital.

Shooting for Gold

Kentarō and Kōtarō took up table tennis while in the sixth grade of elementary school on the recommendation of their mother. The brothers were only mildly interested in the sport at first—they much preferred baseball—but a turning point came when they entered junior high school. “The supervisor of the school’s table tennis club was fervent about the game,” Doi explains. “He instructed us and also introduced us to a para table tennis coach living in Nagoya. Under their guidance our play improved by leaps and bounds and we fell in love with the sport.”

The brothers practiced together, but Kōtarō proved to be the more diligent of the two. While still a senior in high school he was called up to the national team to compete at an international tournament. Doi says he was disappointed at being passed over but took it in stride, insisting that “Kōtarō earned it.”

Another turning point, though, came when Tokyo was tapped in 2013 to host the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. “On hearing the news, Kōtarō and I just naturally started talking about facing off against each other in the gold-medal game,” Doi recounts. He admits that up to then he lacked the drive to play at the top of the sport, but that the idea of making the finals stuck with him and motivated him to work harder. Once the fire was lit, he started training in earnest to make Tokyo 2020 a reality.

Hard work and diligence eventually paid dividends. Shortly after entering Tokai University, Doi was picked along with his brother for the national squad. Kōtarō attended the same university, and the siblings would rush home from classes each day—the brother arriving home first assigned to prepare the evening’s dinner—to practice. Now teammates, they helped each other improve by focusing on filling the holes in each other’s game.

Doi serves during the Thai Open in December 2018. (Photo courtesy of D2C)

Overcoming Loss

The brothers were working toward their Paralympic dream, but fate would intervene in May 2015. Doi recounts that Kōtarō had recently won team gold at a tournament in Osaka, but was dogged by shortness of breath after returning home. Upon visiting the hospital, doctors determined the cause was a faulty heart valve, a condition that needed immediate surgery. Doi was set to play in a tournament overseas when he received the news. Although concerned, he and Kōtarō had been in and out of the hospital regularly as children and he expected this time would be like the others. Telling his brother to “hang in there,” Doi left for the competition as planned.

The operation was a success, but shortly after the procedure Kōtarō’s condition took a turn for the worse and he was placed in intensive care. Upon returning to Japan, Doi rushed to the hospital, but found his twin unresponsive. Visiting each day, he would egg his brother on like he did during matches, telling his twin to “be tough” and “don’t give up.” However, after two weeks in the ICU, Kōtarō succumbed to his condition.

Doi was devastated by the death of his brother. “We were together through thick and thin our entire lives,” he declares. “I would have had a dismal childhood without him—when all the other kids were out on the playground enjoying the games we couldn’t, he was right there by my side, and I was never lonely. We were always there for each other, in life and in table tennis.” He now wears a pendant that contains some of Kōtarō’s ashes, refusing to take it off for even a moment.

At Kōtarō’s funeral, Doi promised his brother he would make it to the final at the Tokyo Paralympics, just as they had talked about.

Keeping His Word

A half year after his brother’s passing, Doi learned that he had the same heart condition. Although fearful he would also die, he went under the knife. There were no complications this time, though, and he made a full recovery.

The experience made a deep impression on Doi. “I often wonder why it was me and not my brother who lived,” he muses. “I want to honor his legacy. But most of all I’m focused on making it to the Paralympics so I can fulfill my promise to him.”

Doi is currently ranked thirty-first in the world, but to earn a ticket to the Tokyo Games he must break into the top 10 by March 2020, when the final rankings are released, a daunting task. There is also the chance of earning a wildcard position, but he remains determined to work his way into the top brackets.

With less than a year to go, Doi is focused as never before. “I have a promise to keep,” he exclaims.

Doi at the D2C head office in Tokyo’s Ginza district.

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview photos by Hanai Tomoko.)