Paralympic Athletes, Up Close and Personal

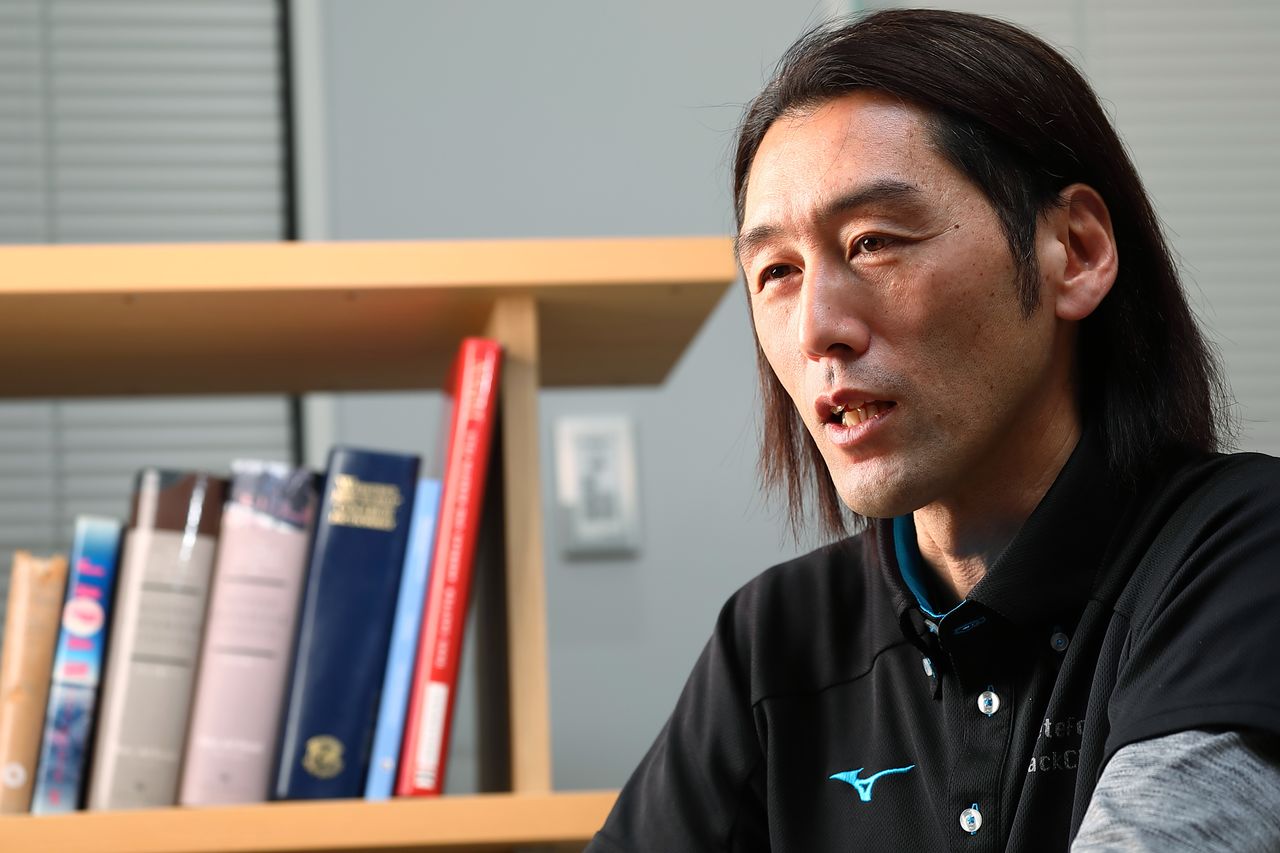

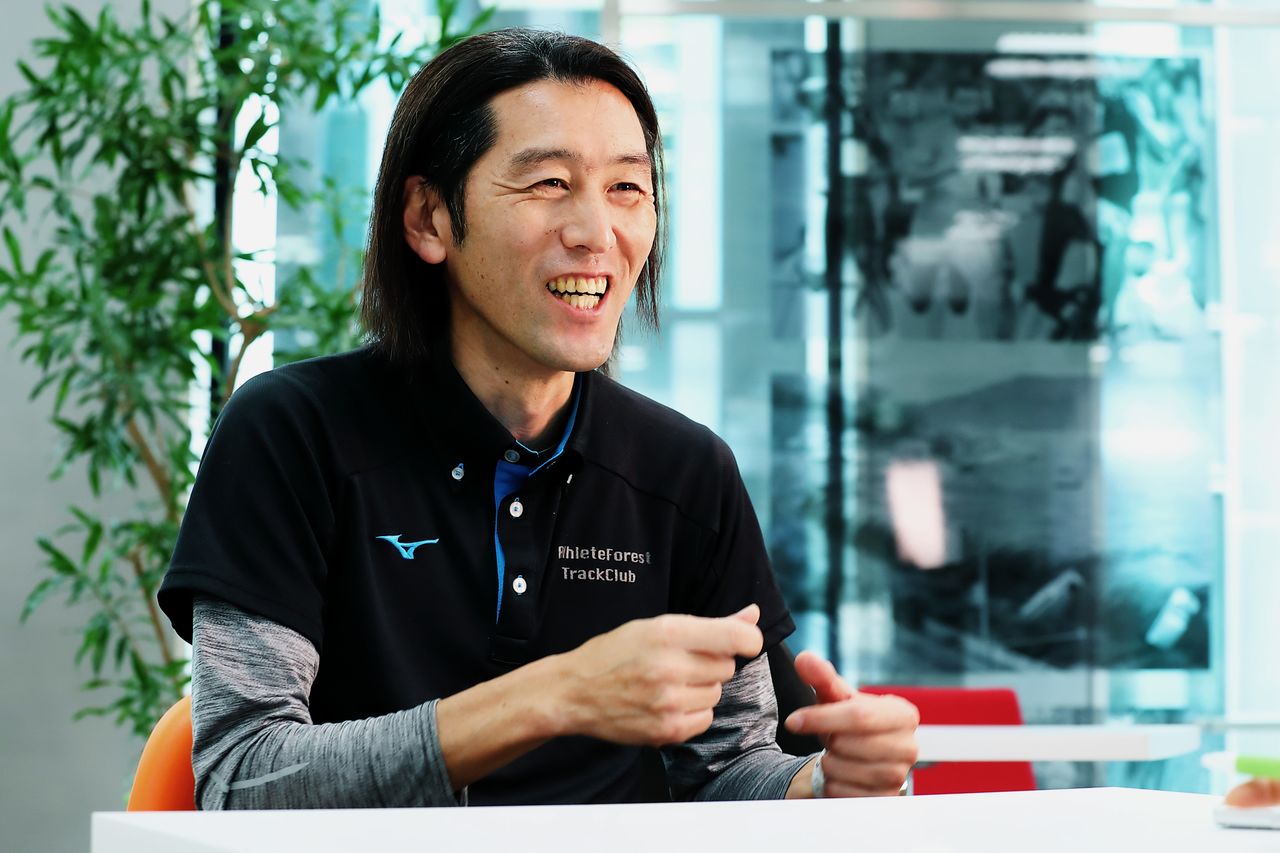

Side by Side: Olympian Ōmori Shigekazu on His Paralympic Guide Runner Role

People Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Staying the Course

The decision to postpone the Paralympics to August 2021 has been met with mixed emotions. On the one hand, athletes and coaches must adjust training schedules and strategies to meet the new start date. But despite the challenges, there is a prevailing sense of relief that the event will go ahead instead of being cancelled, as many had feared.

When they finally get underway, the Tokyo Paralympics will ride a groundswell of excitement surrounding para sports that began in 2012 with the London games. In 2016, interest in the event led more than 4 billion viewers around the world to tune into the Rio de Janeiro Paralympics, and Tokyo is projected to draw similar television audiences. Attendance is also expected to be high. Prior to the postponement, organizers had sold some 600,000 tickets during the first round of the ticket lottery that saw more than 3.5 million applicants.

Social media has helped to drive interest in the Paralympics. More disabled athletes are taking to platforms to share their stories, winning followers and fans with behind-the-scenes looks into the world of para sports.

A distinguishing characteristic of many para events is the roles able-bodied supporters play, including as guide runners and callers for visually impaired athletes. These vital team members race side-by-side with runners and shout out guidance to help participants time their jumps or throws and otherwise orient them during field events. Former Olympian Ōmori Shigekazu wears both hats as coach of Takada Chiaki, serving as guide to the accomplished runner in the women’s 100 meters and caller in the long jump.

A New Role

Takada is a top prospect to represent Japan in the T11 class, the highest level of visual impairment, in both events. She says she has a deep professional bond with Ōmori and continues to improve under his guidance. “He sets the bar high, forcing me to grow as an athlete,” she exclaims. “I can’t even imagine competing without him.“

Ōmori (right) calls for Takada during the long jump competition at the 2019 Kantō Para Athletics Championships in Tokyo.

Ōmori first took notice of Takada in 2006 while helping out at a friend’s athletics club where she trained. In 2008, he opened his own club, Athlete Forest, in Setagaya, Tokyo, and not long after Takada joined to train fulltime under Ōmori. He recalls having some early doubts about working with Takada. “I had zero experience coaching a para athlete,” he explains. “But once we started training, Chiaki blew me away with her competitive drive and passion for the sport. It motivated me to do everything I can as a coach.”

Taking Takada under his wing, Ōmori set out to hone her raw talent by first rebuilding her running form from the ground up. However, to be a guide runner he also had to change his own deeply entrenched habits, a daunting task for the veteran sprinter.

Ōmori (center) crosses the finish line in fifth place in the 4x400 final at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. (© Jiji)

Stride for Stride

During his career, Ōmori competed at the highest level of athletics. In 1992 he was a reserve runner for Japan at the Barcelona Olympics, and in 1996 he anchored the 4x400 relay team in the finals at the Atlanta games, powering the squad to a fifth place finish and a new Japanese record.

While his years on the track served him in his role as a coach, Ōmori struggled to adjust to the mechanics of being a guide runner, which required him to mirror his arm swings, stride, posture, and speed with Takada, who is nearly 20 centimeters shorter. “It was tough, especially reducing my gait and speeding up my steps,” he says, adding with a smile that the effort put him in constant fear of crashing as the pair sped down the track.

Jumping into a New Field

Under Ōmori, Takada increased her speed, setting the Japanese para record in the women’s 100 meters in the runup to the Beijing Paralympics. While she was the reigning champion at home, though, her time was still not enough to win her a berth in the games. Ōmori recalls the disappointment of learning they would sit out the Paralympics, but notes that the sting was lessened when Takada learned she and her husband, deaf hurdler Takada Yūji, were expecting.

Although happy for the couple, Ōmori was certain motherhood would spell the end of Takada’s running career. “It’s incredibly hard to return to racing condition after giving birth,” he explains. Ōmori notes that Takada was also under pressure from her parents to retire. “I braced myself for the announcement, but it turns out she had no intention of hanging up her spikes. Instead, she told me that she wanted to start training for London as soon as possible. End of story.”

After giving birth to a son, Takada returned to the track and was soon running in top form. However, the international ceiling again proved impenetrable, and like with Beijing, she had to accept the bitter disappointment of missing the London Paralympics.

Always quick to bounce back, Takada, her sights set on Rio de Janeiro, suggested changing her focus from the 100 meters to the long jump. Initially taken off guard by the proposal, Ōmori agreed to the ambitious plan.

The long jump for visually impaired athletes is similar to the able-bodied version, with one noticeable difference being the participation of a caller. It employs many of the same techniques and strategies, but Takada, who lost her eyesight as a young girl, had only faint memories of watching the event. Starting with the basics, Ōmori carefully explained each step, from approach to take-off to landing, using his own body as a guide to demonstrate the different motions.

The key to a successful jump is hitting the take-off area at top speed, and Ōmori and Takada worked to get the timing right, settling on a 15-step approach. As her caller, Ōmori diligently counted out each footfall to keep Takada from veering off course and potentially being injured. Beating the odds, Takada succeeded in qualifying for the 2016 games in Rio de Janeiro, where she placed eighth out of a field of 10 competitors.

Bringing up the Next Generation

Since retiring in 2000, Ōmori has held down a variety of jobs along with his coaching activities, including stints at a delivery service company and a life insurance firm. He even played the captain’s role on the popular Tokyo Disneyland attraction Jungle Cruise and served as a gondolier on the Venetian Gondola ride at DisneySea.

He says that each position impressed on him the value of communicating clearly, a skill he admits he struggled with early on. At Disneyland, he had to give succinct instructions to help guests navigate safely and smoothly around the park. He honed his talents further in positions that required him to speak one-on-one with customers.

While Ōmori insists that he did not set out to build his communication aptitude, he says he quickly recognized that ”you can’t get anything done if you can’t make yourself understood.” He has found this holds especially true when coaching a visually impaired athlete like Takada, who relies heavily on verbal instructions.

He also includes his Olympic experience in his coaching skillset. Nerves can have devastating consequences for an athlete, and Ōmori states that having a veteran on the team who knows the pressure of competing at the highest level of the sport is invaluable. This was apparent with Takada’s calm performance at the 2019 World Para Athletics Championships, where she jumped 4.69 meters, surpassing her mark at Rio by nearly 30 centimeters. Although she finished fourth, the result puts her within range of medaling at Tokyo if she continues to improve her performance.

As the pair adjust to the Tokyo Paralympics being moved to 2021, Ōmori says he would like to get more sight-impaired individuals involved in athletics. “In my relationship with Chiaki I’ve held running workshops at schools for the blind,” he explains. “Most institutes don’t include track and field in their curriculums for the simple reason that there’s no one to teach it. As a result, many of the kids have never had the chance to see how fast or far they can run.”

At the same time, Ōmori points out that many professional runners retire feeling they still have something to give to the sport, but lack an avenue to apply their experience. He hopes to develop a system to match these former athletes with visually impaired students, something he is certain would open new horizons for both.

He would also like to bolster support for para athletes by convincing more Olympians like himself of the benefits of coaching disabled athletes. “It’s an honor to be going to the Paralympics with Chiaki,” he proclaims. “I’m excited to be part of the action at the National Stadium in Tokyo, running with her on the track and calling as she hurtles down the runway as the whole world watches. It’ll be just like old times.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview photos by Hanai Tomoko. Banner photo: Ōmori holds a tether used by guide runners.)