Walls Melt Away: Donald Keene as a Teacher and Friend

Culture Books Language- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

“It Doesn’t Get Much Better”

In a 1961 essay in the University of Toronto Quarterly, Donald Keene laments that “the hauntingly beautiful Nō plays are remembered best because of the pun (of which people never seem to tire) between Nō and the common European word of negation.” As Janine Beichman, professor emerita at Daitō Bunka University, recalled during a talk about her former teacher and friend, Keene’s unabashed appreciation of the form was an inspiration to his students.

She told a story about her younger daughter, who had been trying to decide whether to study religion or comparative literature when she attended Keene’s graduate seminar in nō at Columbia University. On the last day of the course, they finished reading Matsukaze (Wind in the Pines), a play in which two ghostly sisters linger on at the beach where they once made salt, yearning for a long-gone former lover. “When they came to the end,” Beichman’s daughter told her, “Keene looked up and his eyes were glistening with tears, and he said, ‘It doesn’t get much better than this, does it?’”

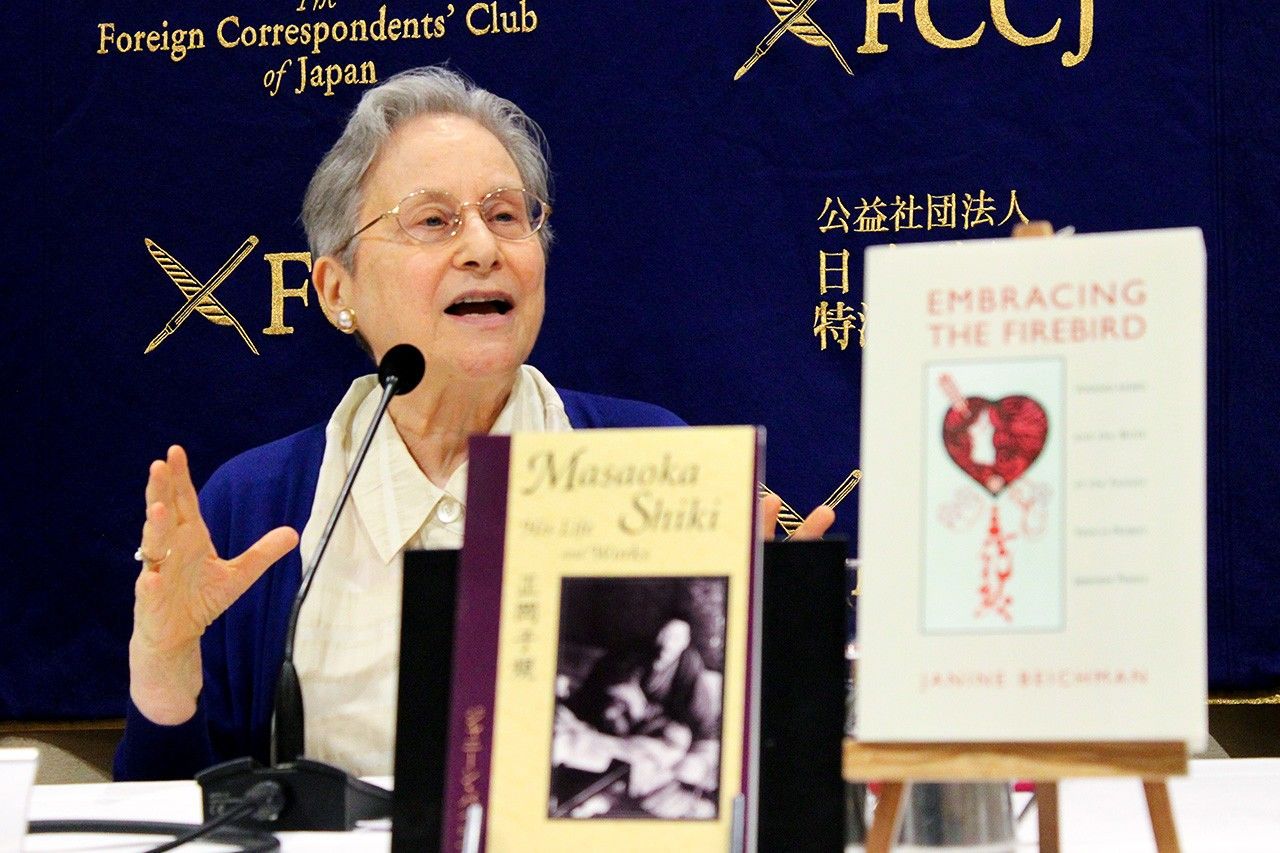

Janine Beichman speaks about her mentor Donald Keene at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan in Tokyo on January 22, 2020.

Even after teaching the text for at least 30 years, he still found it moving—and this passion made Beichman’s daughter’s mind up to opt for literature. Beichman herself was drawn into her field of expertise by a 1963 encounter with the anthology Modern Japanese Literature, which was edited by Keene. Entranced in particular by an excerpt from Mishima Yukio’s Confessions of a Mask, she became Keene’s graduate student later that same year, studying with him until she received her doctorate in 1974.

A World Without Barriers

After a few years in which she built up her knowledge of the language from scratch, she began seminars on such writers as the poet Bashō, the nō playwright Zeami, and the jōruri and kabuki dramatist Chikamatsu. It was quite a jump to read such literary texts from centuries ago, but Keene, by turns demanding and inspiring, made it possible. Beichman described how in a 1967 nō seminar, students did not bring written English versions of the texts to class, instead reading the Japanese aloud and then translating it on the spot.

They would begin as literally as possible, before refining and improving. “When we arrived at a translation that was not only faithful to the exact meaning of the Japanese but also beautiful as English,” Beichman said, “it seemed to me that the wall between the two languages had melted away, and I had entered a transparent world without barriers.” Keene’s seminar students ultimately produced enough translations to make up the book 20 Plays of the Nō Theatre, which was published in 1970.

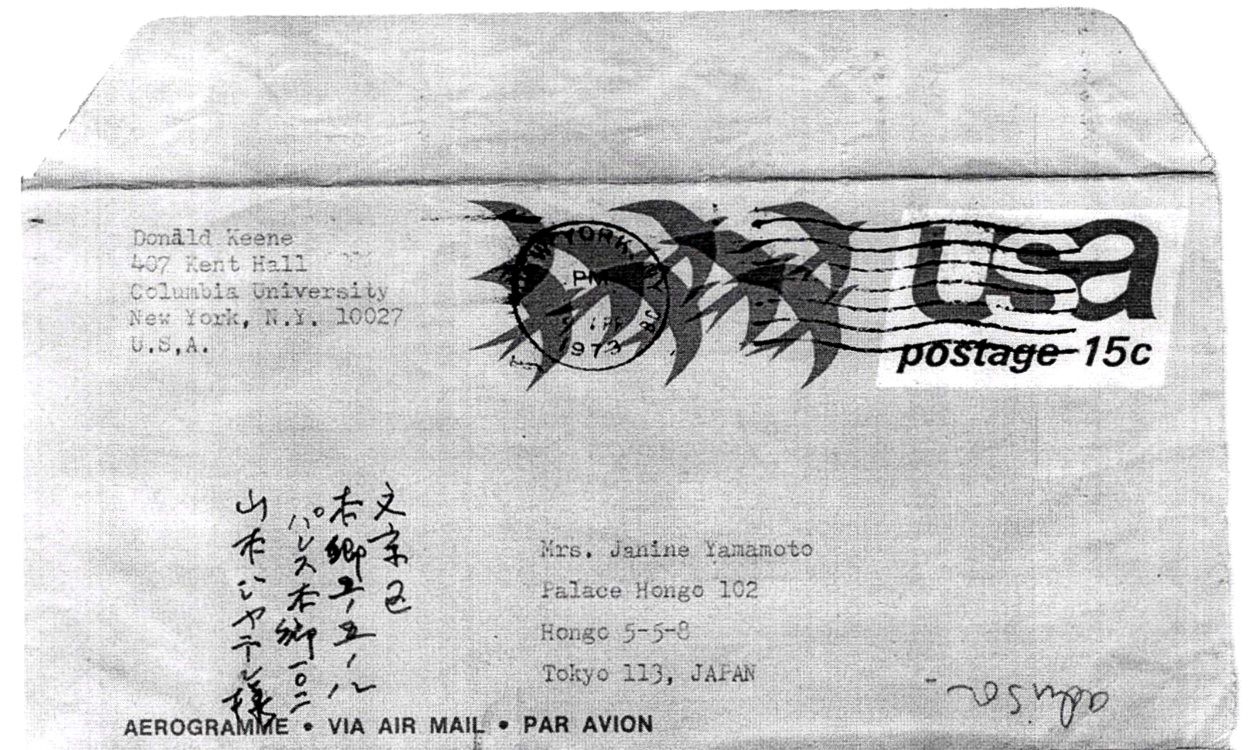

Beichman went to Japan on a Fulbright-Hays fellowship to write her doctoral thesis on the poet Masaoka Shiki in 1969, and Keene became her thesis advisor. They corresponded by letter. Her manuscripts came back from him covered in comments, which could be both discouraging and energizing. Yet overall, he was supportive. While writing her thesis, she married and became pregnant, and Keene responded with both congratulations and encouragement about her thesis defense.

A letter from Keene addressed to Beichman under her husband’s name.

She noted how even today male teachers might describe female graduate students with children as “lost to academia,” but Keene was never like that. “This is probably why he had so many female students who went on to have their own careers.” She traveled to New York to defend her thesis when her elder daughter was two months old; while she went to Columbia, her mother looked after the baby. Keene helped to ensure her defense was successful when other examiners, who had different takes on how to render Japanese verse, criticized the translations of haiku and tanka she had included.

Keene Was There

His faith in Beichman’s work was justified, as she developed her thesis into the 1982 book Masaoka Shiki: His Life and Works, the poet’s first biography in English, which received critical praise and is still in print today. A quarter of a century later, a surprising development came in a 2008 email from Keene, who had recently received the Order of Culture from the Japanese government. He was thinking about writing another biography, possibly about Shiki, but, he wrote, “I would not wish to endanger our friendship.”

“I was simply floored by this,” Beichman remembered. Keene had recommended Shiki to her and supervised her thesis. He was her teacher and she could not initially understand why he would need to worry about her feelings. But their teacher-student relationship had been subtly morphing into friendship over the years, and this email brought it home to her. With her blessing, Keene went on to write The Winter Sun Shines In: A Life of Masaoka Shiki.

While Beichman shared her enjoyment in looking back on the feisty young Keene’s attack on the careless dismissal of Japanese literature in the West in his 1961 essay, she stressed his active, transformational role over the decades of his career. He changed the conditions he criticized, teaching the next generation of Japan scholars and translators at Columbia. “For people who really wanted to learn, Keene was there, ready and willing and eager to educate us.”

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: Janine Beichman and Donald Keene in Tokyo in 2017. © Suzuki Nobuyuki. Profile and envelope photos courtesy Janine Beichman.)