A Walk Around the Yamanote Line

From Tabata to Sugamo: Greenery and Graves at the Northern Tip of the Yamanote

Travel- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

At the Hilly Border of Yamanote and Shitamachi

When I step outside Tabata Station, I stop to take in the unusual scene. Tabata doesn’t open onto a busy plaza or a commercial zone like elsewhere. There is nearly nothing around the station. Instead, the land falls away almost immediately, the tracks cutting through a shallow trench below. From the north exit, the view spreads toward a uniform expanse of rooftops and backstreets. There’s a sense of space here, a pause in the city’s density.

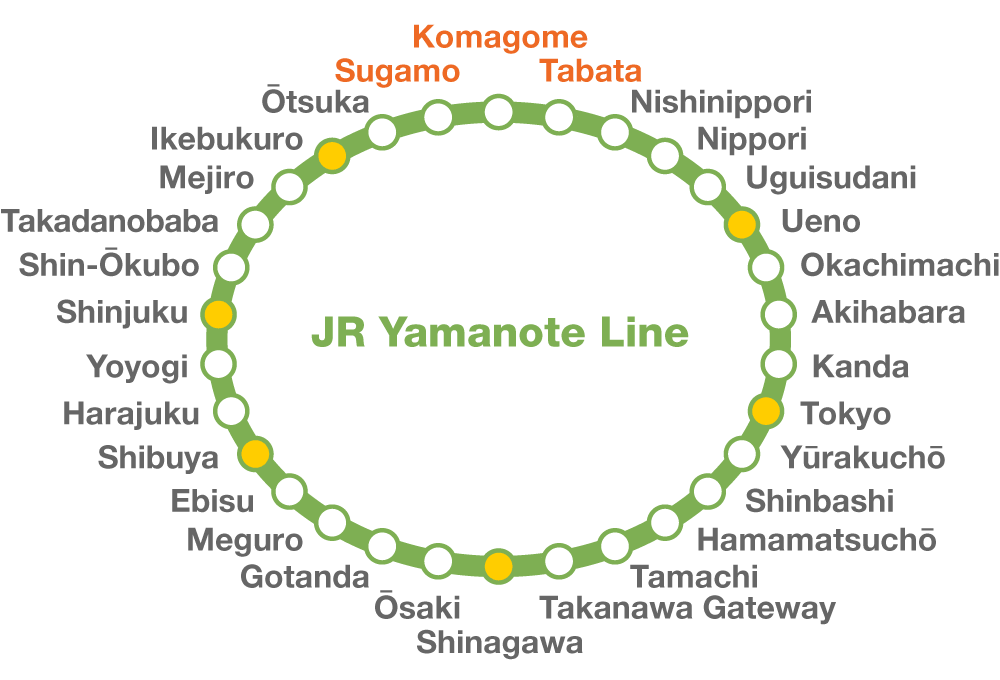

The stations on the Yamanote line stations loop. (© Pixta)

Tabata has always been a place of thresholds, built on the seam between two different Tokyos: the high ground of the Yamanote, the “hillside” districts to the west, and the flat basin of the Shitamachi to the east, a natural divide that has shaped both its geography, human settlement, and people’s imagination. Here the Yamanote Line tracks pass through a kind of cutting or trench, with retaining walls and viaducts. Looking at the landscape from the bridge you get a clear idea of Tokyo’s undulating topography forcing railways to slice through hills.

A Yamanote Line train hugs the sharp Tabata ridge, tracing the fault between the homes above and the maze of tracks below. (© Gianni Simone)

Time to move my feet. Heading west, I’m met by a steep slope that quickly funnels into a sunken road. The grade is sharp enough to feel like a descent into another layer of the city. The road is flanked by high retaining walls, with pedestrian paths elevated slightly on both sides. It’s a man-made ravine, with buildings perched above like cliffs.

Wandering through the narrow backstreets, I come across a vacant plot enclosed by a chain-link fence. A sign fastened to it announces the future site of the Akutagawa Ryūnosuke Memorial Museum. His house used to be located here, but for now, there is only gravel and weeds.

In the mid-Meiji era (1868–1912), Tabata was a farming village of groves and fields. But after the Tokyo Fine Arts School opened in nearby Ueno in 1889, young artists began settling here. By 1900, figures like Kosugi Hōan and Itaya Hazan had arrived, followed by sculptors, metalworkers, and painters. The Poplar Club formed, and by the end of the Meiji era, Tabata had become an “art village.”

From 1914, the area drew literary talent as well. Akutagawa lived here until his death in 1927, writing many of his major works and helping shape Tabata into a bungei mura—a “literary village.” His presence attracted writers like Muroo Saisei, Hagiwara Sakutarō, and Hori Tatsuo, who found inspiration in the ridge’s light, air, and views over Nippori and the flow of the Arakawa. That talented community is now celebrated at the Tabata Memorial Museum of Writers and Artists.

The Tabata Memorial Museum of Writers and Artists celebrates the creatives who lived in the area in the early twentieth century. (© Gianni Simone)

Crimson Guardians Stand Watch

Keeping to the right of the canyon, I follow Route 458 until I reach a small cemetery—the cue to dive into the warren of narrow alleys to the right. After a while, it’s easy to grow weary of temples and shrines; they blur together, indistinguishable from one another, their names and deities dissolving into one long continuity of incense and gravel paths. But now and then you are granted a surprise and rewarded with a hidden gem that momentarily restores your curiosity.

The place I stumble upon this time is one of those exceptions. Tabata Hachiman Shrine unfolds across both high and low ground, with stone staircases connecting the upper worship hall and lower approach. This vertical arrangement creates a sense of progression. In Shintō architecture, climbing toward the honden (main hall) mirrors spiritual elevation. The layered layout reinforces this metaphor, each step a sort of offering.

Tabata Hachiman Shrine’s layered layout unfolds like a vertical pilgrimage. (© Gianni Simone)

Visitors pass through multiple torii gates as they climb, each marking a threshold. I’ve actually entered from the back door, so I walk down instead of climbing up the stairs, which in a sense, makes it even more unusual.

As I leave Hachiman Shrine and turn right, I’m met by a flash of color: two bulky shapes covered entirely in bright red paper. This is the temple Tōkakuji, home of the Akagami Niō, the “red-paper guardians.” The Niō are those fierce, muscular sentinels you see at many temple entrances, their expressions frozen somewhere between fury and compassion. Here, though, their wrath has softened under the weight of centuries of human touch. Millions of petitioners have transformed them into something else entirely: papier-mâché deities of communal hope, longing, and pain.

The Akagami Niō are revered for warding off misfortune and curing illness. (© Gianni Simone)

The ritual is straightforward and almost domestic. At the back of the compound, you knock on the wooden door of the temple office, where a caretaker sells incense and small squares of crimson paper already dabbed with paste. You light the incense and offer it before each statue. Then you press the paper where it belongs. A knee, a shoulder, a toe. Those suffering from a stiff shoulder place their plea on the Nio’s own, trusting him to bear the dull weight of their discomfort. Nearby, a cluster of straw sandals hangs from hooks—tokens from those who claim to have been cured.

At the Hilly Border of Yamanote and Shitamachi

I arrive in Komagome and Tokyo runs backstage for another change of costume. Tabata’s semiposh, scarcely populated district morphs into a much livelier hood, closer to a Shitamachi mood. Inevitably, the shopping street is called Komagome Ginza.

The lively shopping street in front of Komagome Station. (© Gianni Simone)

Lively Shopping and Green Graveyards

It’s a typical shōtengai, or shopping district: elderly couples browsing produce under a green awning, crates of grapes and kiwis spilling onto the sidewalk, handwritten price tags curling in the sun. A woman with a parasol passes a herbal pharmacy, its glass windows lined with kanpō remedies and faded posters. It’s a corridor of daily rituals—modest, textured, and endearingly eccentric.

Komagome is a rare pocket of nature along the Yamanote Line. A map of Tokyo shows a number of green splotches around the station—far more than most other Yamanote stations can boast. This part of my walk keeps spinning me away from the tracks. I have to choose my detours, and this time the popular Rikugien and Kyū-Furukawa Gardens are the ones I let go as I’ve been there many times.

Instead, I abandon the dull main avenue heading north from the station and turn left into the Shimofuri shōtengai, one of those deeply local shopping streets that never fail to make me smile. The air carries the scent of produce and grilled fish. A woman with a floral umbrella strolls ahead, unhurried. Inside the greengrocer, crates of vegetables are stacked with handwritten price tags: tomatoes, corn, onions, and greens, all arranged with typically Japanese, almost exaggerated care.

The greengrocer in the Shimofuri shōtengai arranges his goods with typically Japanese care. (© Gianni Simone)

I advance deeper into Nishigahara 1-chōme and Komagome 6-chōme, once part of the old village of Somei, famous for its gardeners and the cherry tree varieties they cultivated, including the Somei-yoshino that would eventually blanket the nation in spring. In the mid-nineteenth century, the villages of Somei and nearby Sugamo were not yet part of Tokyo (then a city far smaller than its present metropolitan boundaries) but a hub of horticultural innovation. Hard to picture now, with convenience stores and apartment blocks, but in the 1860s the area had grown so dense with nurseries and specialist growers that the British botanist Robert Fortune stood somewhere around here and called Somei and Sugamo the world’s largest flower and plant center, writing in his 1863 Yedo and Peking: “I have never seen, in any part of the world, such a large number of plants cultivated for sale.”

Eventually, I turn into Somei-zaka, a long straight slope—more in name than in steepness—and then the equally long and straight Somei-dōri that carries me toward Somei Cemetery, one of central Tokyo’s four metropolitan graveyards. At just under 7 hectares, it is the smallest, but to my eye the most beautiful, so much so that it almost reads as a public park. Around a hundred Somei-yoshino cherry trees are planted throughout the grounds, turning the cemetery into a celebrated hanami spot each spring.

Somei Cemetery’s overgrown lanes sit next to the Sugamo wholesale vegetable market (in the background). (© Gianni Simone)

Tokyo, I’ve found, has cemeteries that mirror the city itself. Each graveyard feels like a miniature Tokyo: rows of vertical rectangles in granite, marble, and concrete, tightly packed together like office towers. Walk between them and you could almost believe you’re strolling through a scaled-down model of the metropolis: dense, scattered, No vending machines, though. Not yet.

But life goes on inside the gates. A group of retirees has turned a clearing into a kind of open-air clubhouse, bicycles lined up neatly beside the path. Bird-watchers scan the canopies with binoculars. Yet none of this breaks the atmosphere.

As I leave Somei, I realize that recently these places have acquired added value. In the past, when fires were a constant threat in Tokyo, cemeteries often served as firebreaks. Today they serve a different but equally vital purpose: not against flames, but against the fires of unchecked redevelopment. People living in the city need their green spaces, and Tokyoites do not seem to mind sharing them with the dead.

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: The narrow alleys of Tabata and Komagome feature thriving private gardens, a throwback to the area’s heyday as a leading nursery center in the capital. © Gianni Simone.)