Tōshūsai Sharaku: The Mystery Artist of Iconic Actor Portraits

Culture Art History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Complete Unknown

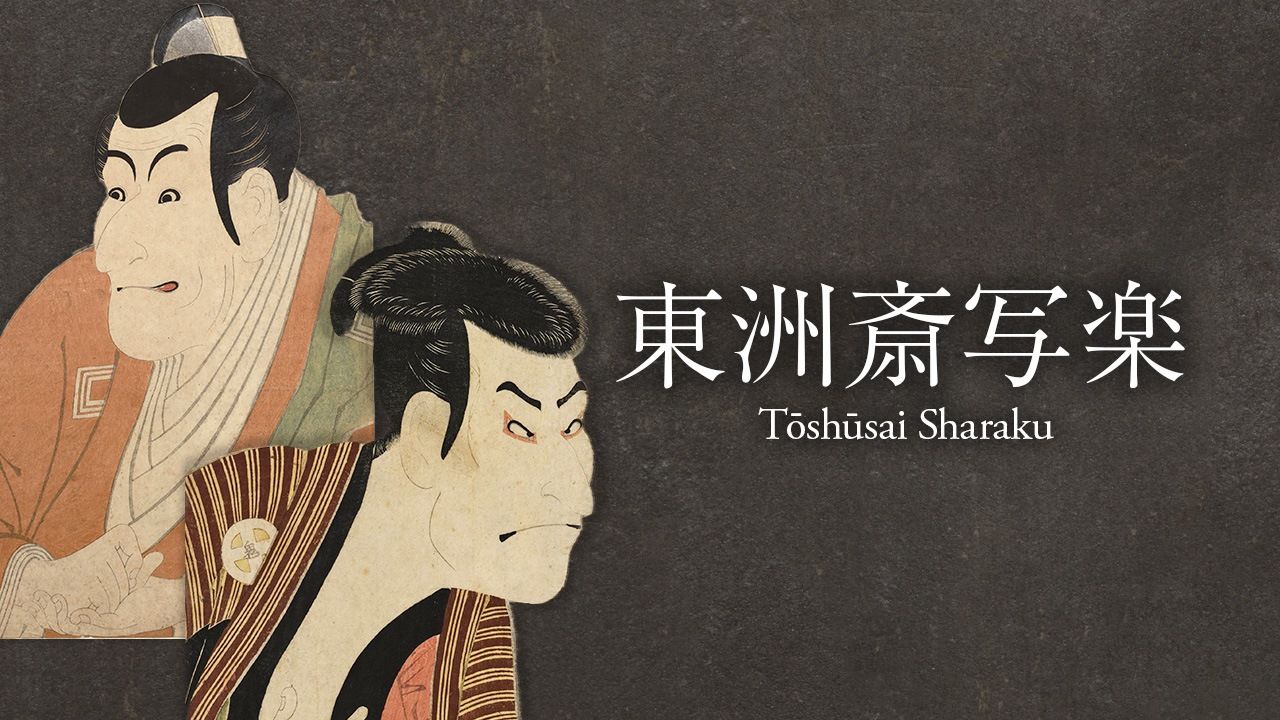

In the early summer of 1794, the leading Japanese publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō simultaneously brought out 28 large portraits of actors, gorgeously finished with backgrounds of black mica powder. The artist was an unknown called Tōshūsai Sharaku. There had never previously been actor portraits with these kinds of backgrounds before, and in combination with the boldness of the designs, it is easy to imagine the sensation they caused.

The theater world of Edo (now Tokyo) had a reputation as a place where big money was always moving. In the culturally vibrant Kansei era (1789–1801) when Sharaku was active, one might imagine that kabuki was at its most splendid, but in fact it was quite the opposite. The Kansei reforms instituted by the shogunate’s senior councilor Matsudaira Sadanobu put the economic squeeze on Edo’s three licensed kabuki theaters, bringing their business to a standstill, and by 1794 (Kansei 6) performances were limited to substitute venues with temporary performance licenses. However, the crisis also meant opportunity. Theater managers, teahouses associated with the theaters, and investors looked for new promotion methods. After a major fire in the spring stalled productions in the Yoshiwara pleasure district, Tsutaya, who was looking to enter a new field, took a chance on Sharaku.

Just 10 months after his debut though, Sharaku disappeared from the historical record, having performed the exceptional feat of producing more than 140 prints for publication in less than a year. It might seem that it would be easy to keep track of such a masterful artist, but this is not the case. During the Edo period (1603–1868), social status was all-important and ukiyo-e painters were not considered to be true artists. Their woodblock prints, available to the general public, were thought to be disposable, and there were different words for distinguishing ukiyo-e artists (gakō) from the higher status artists working for the shogunate known as eshi. We know almost nothing of the lives of Suzuki Harunobu, who pioneered full-color nishiki-e prints, and Sharaku’s contemporary Kitagawa Utamaro. The people of the Edo period seem to have had little interest in the lives of woodblock artists.

No Deference

Sharaku’s works were more than just simple portraits. They depict the actors as they perform, and it is even possible to identify the scene. These works, in which the form and expression matches the performance, can be broadly divided into four periods.

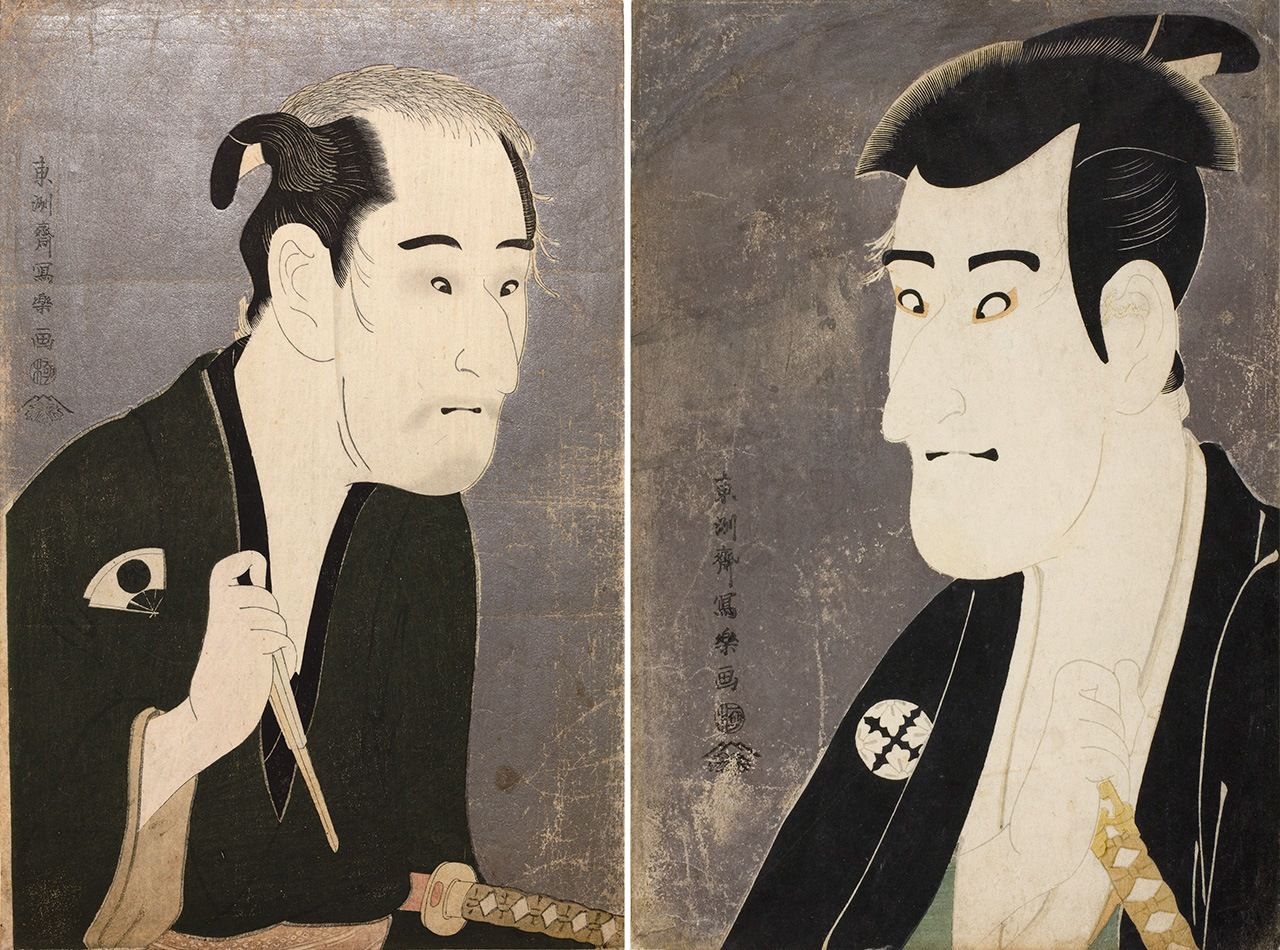

The first period was in the early summer of 1794, when Sharaku produced his 28 large portraits depicting kabuki at a substitute theater. All are nishiki-e with black mica powder backgrounds, around 37 centimeters tall by 25 centimeters wide, and they are ōkubie that only show the head. Of these, five include two actors.

Sandaime Sanogawa Ichimatsu no Gionchō no hakujin Onayo (The Actor Sanokawa Ichimatsu III as the Gion Prostitute Onayo) (left) depicts a masculine-looking performer; Ichikawa Ebizō no Takemura Sadanoshin (The Actor Ichikawa Ebizō as Takemura Sadanoshin) portrays a profound performance by the leading actor of his generation. (Both courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase)

The ōkubie being like later commercial photos of movie stars, it was typical for artists to pay more attention to pleasing the fans who were the likely purchasers of these prints, rather than being faithful to how the actors appeared in performance. However, Sharaku showed no deference to these fans, instead producing highly realistic portraits that exaggerated the actors’ characteristics.

For example, his pairings of Edobei and Ippei, or Matsushita Mikinoshin and Shiga Daishichi, are based on particularly dramatic scenes.

Sandaime Ōtani Oniji no Edobei (The Actor Ōtani Oniji III as Edobei) (left) and Shodai Ichikawa Omezō no yakko Ippei (The Actor Ichikawa Omezō as the yakko Ippei). Edobei attacks the servant Ippei to steal the money he is carrying. Oniji may have performed this pose before the play; other artists depict the same stance. (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase)

Shodai Onoe Matsusuke no Matsushita Mikinoshin (The Actor Onoe Matsusuke as Matsushita Mikinoshin) (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase) (left) and Sandaime Ichikawa Komazō no Shiga Daishichi (The Actor Ichikawa Komazō as Shiga Daishichi) (Courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago). Mikinoshin has fallen in the world and suffers from poverty and illness, while Daishichi is the villain who kills him.

Sharaku skillfully depicts the actors’ gestures and body movements, including hands gripping swords or splayed fingers, and the nature of the characters they play. The black mica backgrounds work effectively to highlight these performers.

Diminished Individuality

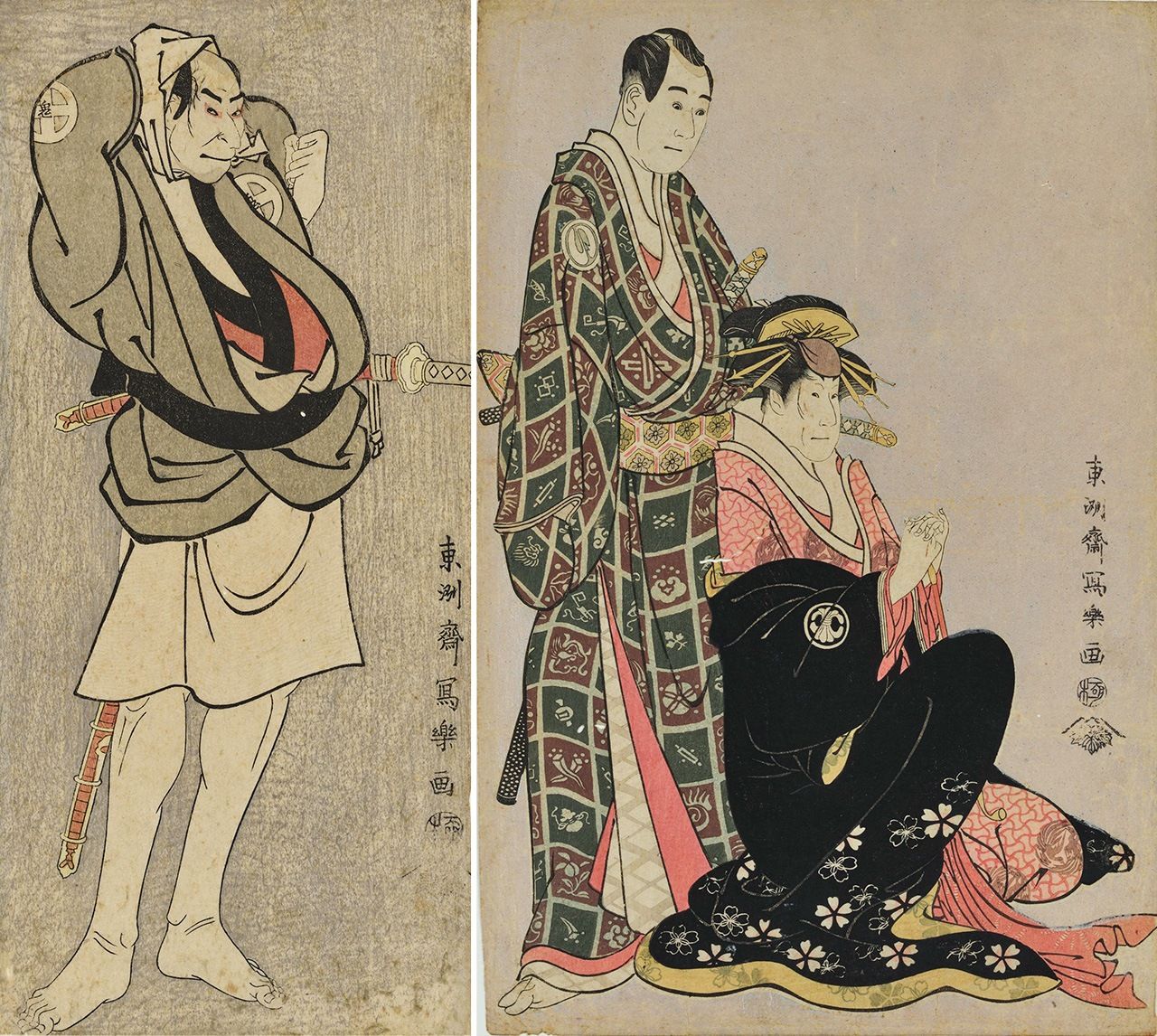

The pictures released in Sharaku’s second period, during the late summer and early autumn of 1794, were all full-length portraits. These were in the traditional format of around 33 centimeters tall by 15 centimeters wide and were painted without backgrounds; in many cases, individual portraits could be combined to create a stage scene. They often feature Sharaku’s classic use of curved lines to express movement and posture.

Large portraits from this period have mica backgrounds, and their composition emphasizes the visual effect of circles and triangles, such as by putting two figures together to form an arc or placing them on one side of a diagonal line. Unlike the imposing style of the first period, costumes in the second period are in showy colors to match well with the white or yellow backgrounds and detailed patterns also draw the eye. Tsutaya may have aimed to expand his market by focusing on inexpensive prints.

Shinozuka Uraemon no Miyakoza kōjōzu (Shinozuka Uraemon Reading the Prologue at the Miyakoza Theater). Rather than details of the kabuki to be performed, the text on the theater manager’s paper here actually announces a second series of portraits published by Tsutaya. (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase)

Sandaime Ōtani Oniji no Kawashima Jibugorō (The Actor Ōtani Oniji III as Kawashima Jibugorō) (left) and Sandaime Sawamura Sōjūrō no Nagoya Sanza Motoharu to sandaime Segawa Kikunojō no keisei Katsuragi (The Actors Sawamura Sōjūrō III and Nagoya Sanza Motoharu and Segawa Kikunojō III as the courtesan Katsuragi). (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase)

Sharaku’s third period came toward the end of 1794, with works depicting the kaomise (literally “face-showing”) kabuki performances of this time of year, introducing new actors. He produced a relatively large number of pictures, with 58 having been identified. However, many do not survive, or only do so in one copy, indicating an apparent lack of commercial success. They lack Sharaku’s typical clarity, with diminished individuality. They seem to have been made as souvenir pictures of popular actors, as they include the performers’ stage names and pen names. These pictures show a limited range of expression and appear flat and formalized, especially when compared with the works of the first period, which give a dramatic sense of the characters performed by the actors.

Sakaiya Shūkaku (left) and Sandaime Sawamura Sōjūrō no Kujaku Saburō Narihira (The Actor Sawamura Sōjūrō III as Kujaku Saburō Narihira) show an unusual level of focus among the works of the third period. (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase)

From Sharaku’s fourth period, just 10 pictures remain, depicting actors in the comic kyōgen plays for the New Year in the traditional calendar, which took place in early 1795. While many of the third-period works presented backgrounds only impressionistically, the fourth-period paintings emphasize the stage settings, and the costumes and outlines of figures have become monotonous.

These pictures were painted in advance and published to coincide with the first day of performances. They are the last works by Sharaku before his sudden disappearance less than a year after his debut. In a drastic transformation from his breakthrough, there is no trace of his earlier powerful individuality. The 10 extant actor pictures give a sense of hurry and incompletion, suggesting that the commercial venture foundered. The change in style from the third period also invites speculation that another artist was painting under the Sharaku name.

From left, Nidaime Bandō Mitsugorō no Soga no Gorō Tokimune (The Actor Bandō Mitsugorō II as Soga no Gorō Tokimune), Sandaime Sawamura Sōjūrō no Soga no Jūrō Sukenari (The Actor Sawamura Sōjūrō III as Soga no Jūrō Sukenari), and Sandaime Bandō Hikosaburō no Kudō Saemon Suketsune (The Actor Bandō Hikosaburō III as Kudō Saemon Suketsune) combine to form a scene from a New Year story about the Soga Brothers. (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase)

Daidōzan Bungorō no goban age (Daidōzan Bungorō Holding Up a Go Board) is a picture not of an actor but of a popular, huge child sumō star. (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase)

Rediscovery in Europe

“Sharaku painted portraits of kabuki actors, but he tried to paint them so realistically, and painted them so badly, that they didn’t catch on and were finished after a year or two.”

This is how Sharaku is described in Ukiyo-e ruikō (Various Thoughts on Ukiyo-e) by Ōta Nanpo around 1798. Many works from Sharaku’s debut collection remain, so it is likely a large number were printed, but there seems to have been a decline in the numbers of later pictures published. It appears that Tsutaya’s big commercial gamble did not pay off, resulting in the loss of sponsors and eventual failure. Sharaku’s style was out of step with what the kabuki fans of the day wanted, so it was only natural that his career was a brief one.

In 1910, the German art historian and Japanophile Julius Kurth published Sharaku, a study of the artist. Following earlier works on Utamaro (1891) and Hokusai (1896) by the French art critic Edmond de Goncourt, there was considerable enthusiasm in the West for ukiyo-e at this time. Kurth and other Europeans who were unfamiliar with kabuki are likely to have appreciated Sharaku’s works as striking portraits, reflecting inner feelings, rather than seeing them as the favorite actors of the day. Contemporary Japanese now enjoy them in the same way.

Based on later additions to Various Thoughts on Ukiyo-e by writers like Santō Kyōden and Shikitei Sanba, as well as other Edo period materials, Sharaku is now generally thought to have been the nō actor Saitō Jūrobei from the Awa Tokushima domain (now Tokushima and Hyōgo Prefectures).

(Originally published in Japanese on June 24, 2025. Banner image created using works by Sharaku. Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase.)