Tsutaya Jūzaburō: The King of Edo Publishing

History Economy Entertainment Art- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Modest Beginnings

Tsutaya Jūzaburō (1750–97), a leading publisher in eighteenth-century Japan, won a reputation for selling a string of hit books, including guides to the red-light district of Edo (now Tokyo).

From the seventeenth century, organizations known as jihon don’ya acted as both publishers and booksellers for entertaining works produced in the Japanese capital of Edo. They cornered the market by acquiring the rights to the woodblocks required for printing specific books. Forming a guild, they ensured that no group infringe on the publication rights of another, which served to keep piracy of works in check.

Tsutaya made a modest start renting and selling books in a small store outside the main gate of the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters. The books included Yoshiwara saiken, a series of guides providing information on the area’s brothels and courtesans. In 1774, he acquired the rights to print other types of guides to Yoshiwara and entered the publishers’ guild. By 1783, he had a monopoly on such guides.

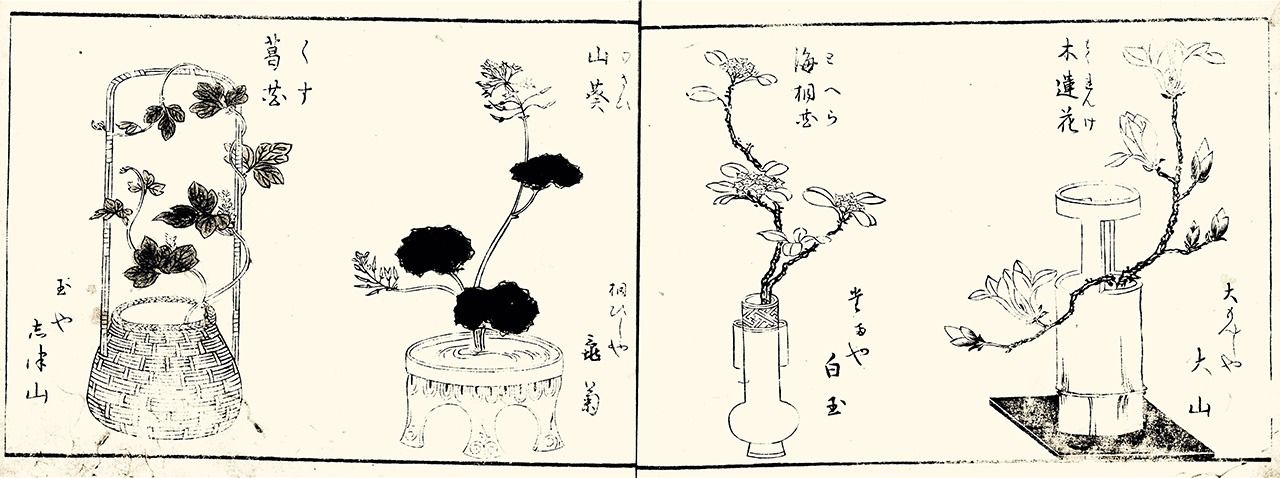

His first publication, Hitome senbon (A Thousand at a Glance), was a review in the mold of Yoshiwara saiken that compared the women of the quarter to different flowers and plants like magnolias or wasabi. While the work was of little practical use to the general public, its lavish production was well received by the brothels and customers of Yoshiwara, and who may have provided the financing to publish it in the first place.

Tsutaya Jūzaburō’s first publication Hitome senbon. (Courtesy the National Institute of Japanese Literature)

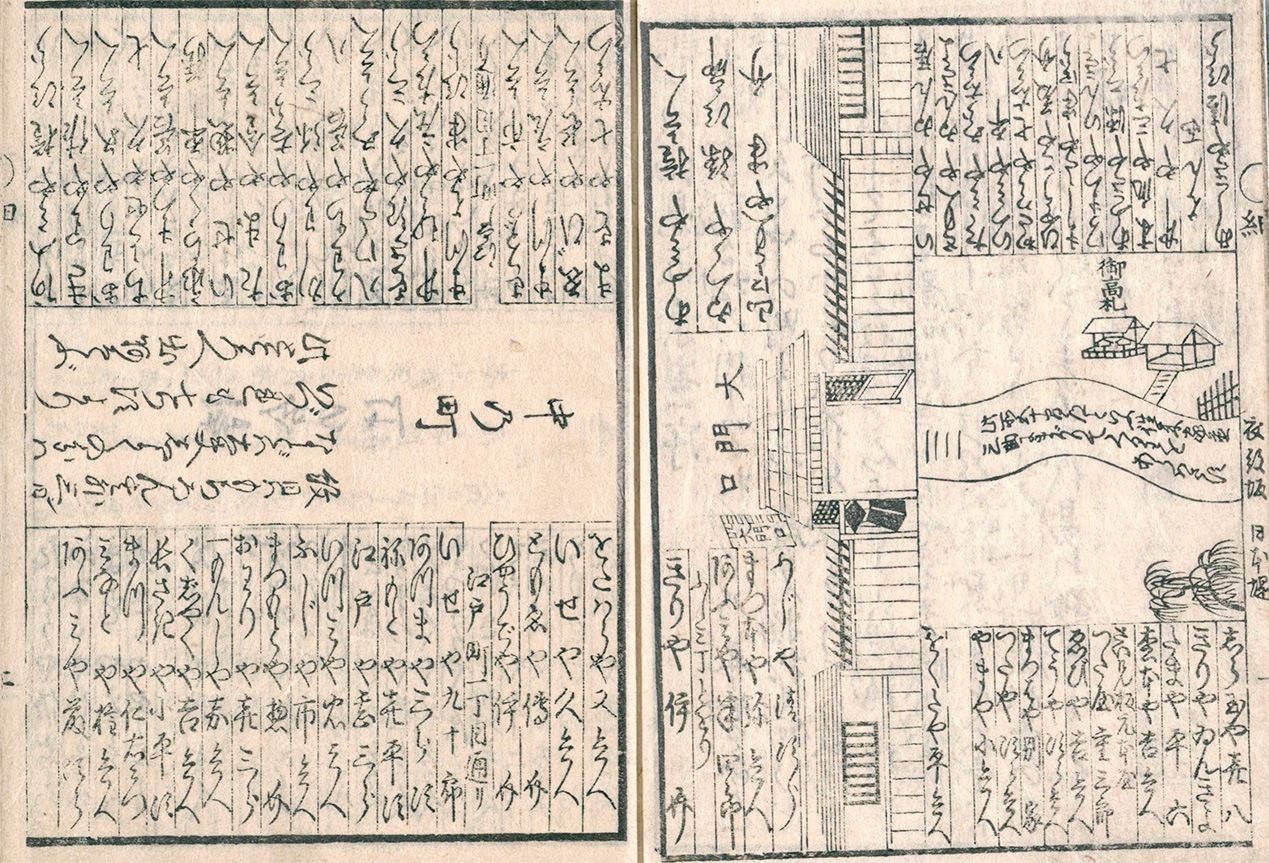

The Yoshiwara guide Goyō no matsu (Five-Needled Pines) shows the main gate to the right and the Nakanochō main street to the left, lined with brothels. From 1783, when the guide was published, Tsutaya had a monopoly on its production. (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

Tsutaya demonstrated a keen business sense in starting out as Yoshiwara’s bookseller, a venture that came with little risk of failure given the red-light district’s popularity.

Publishing regular updates of guides was challenging given the steady turnover in Yoshiwara. However, after several years in business, Tsutaya was able to secure accurate information on which courtesans were working where from sources like his father, who worked in the district, making it easier to get the details he needed. Using this information, he published a practical guide called Goyō no matsu (Five-Needled Pines).

Tsutaya specialized in political materials that satirized the samurai class, leading some scholars to characterize him as an early example of anti-establishment media. In truth, he carefully read the atmosphere of the times, relying on his sharp business acumen to meticulously provide information to the public.

Supplying Entertainment to Edo

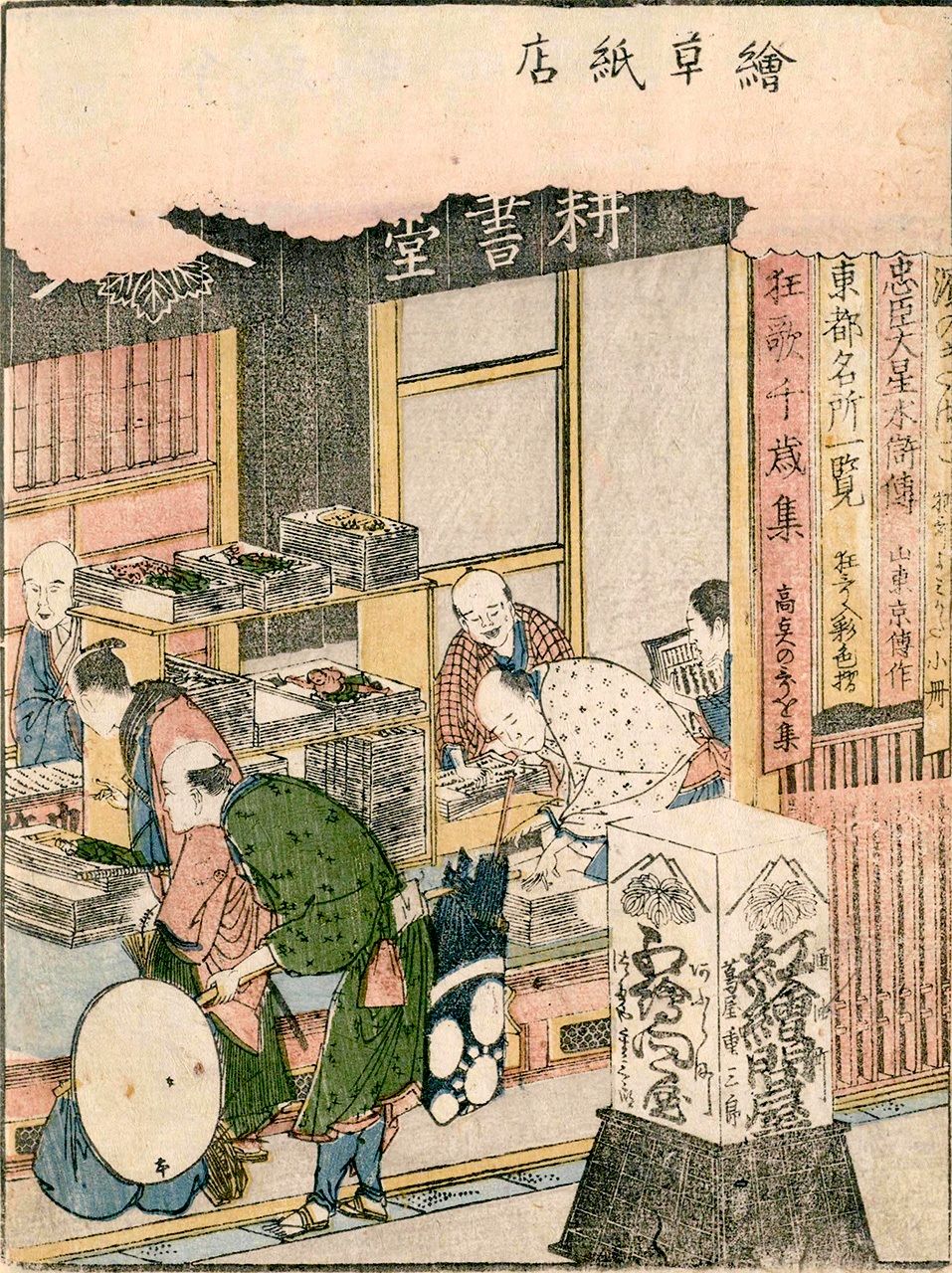

Tsutaya moved his operation to Nihonbashi in 1783 where many other major publishers were based, opening the Kōshodō publishing house and bookstore, which would be the site of further successes.

Kōshodō is included in Katsushika Hokusai’s Ehon azuma asobi (Picture Book of Edo Amusements). The work was published in 1802 and is thought to depict the store after Tsutaya’s death. (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

Edo in the late eighteenth century boasted a high rate of literacy, and books were popular entertainment. Apart from the gakujutsusho works for scholars and researchers on topics like Confucianism or topography, there were many kinds of entertaining books, including gesaku (light fiction), kyōkabon (humorous poetry), kusazōshi (illustrated books), ehon (picture books), and sharebon (“witty books” about the pleasure quarters). Tsutaya had big sellers in all of these entertaining genres.

One of his specialties, though, was kyōka. These “wild” waka followed the classical 5-7-5-7-7 form, but put a premium on comedy over elegance. They were all the rage in 1780s Edo, and kyōkahon combined the poems with illustrations.

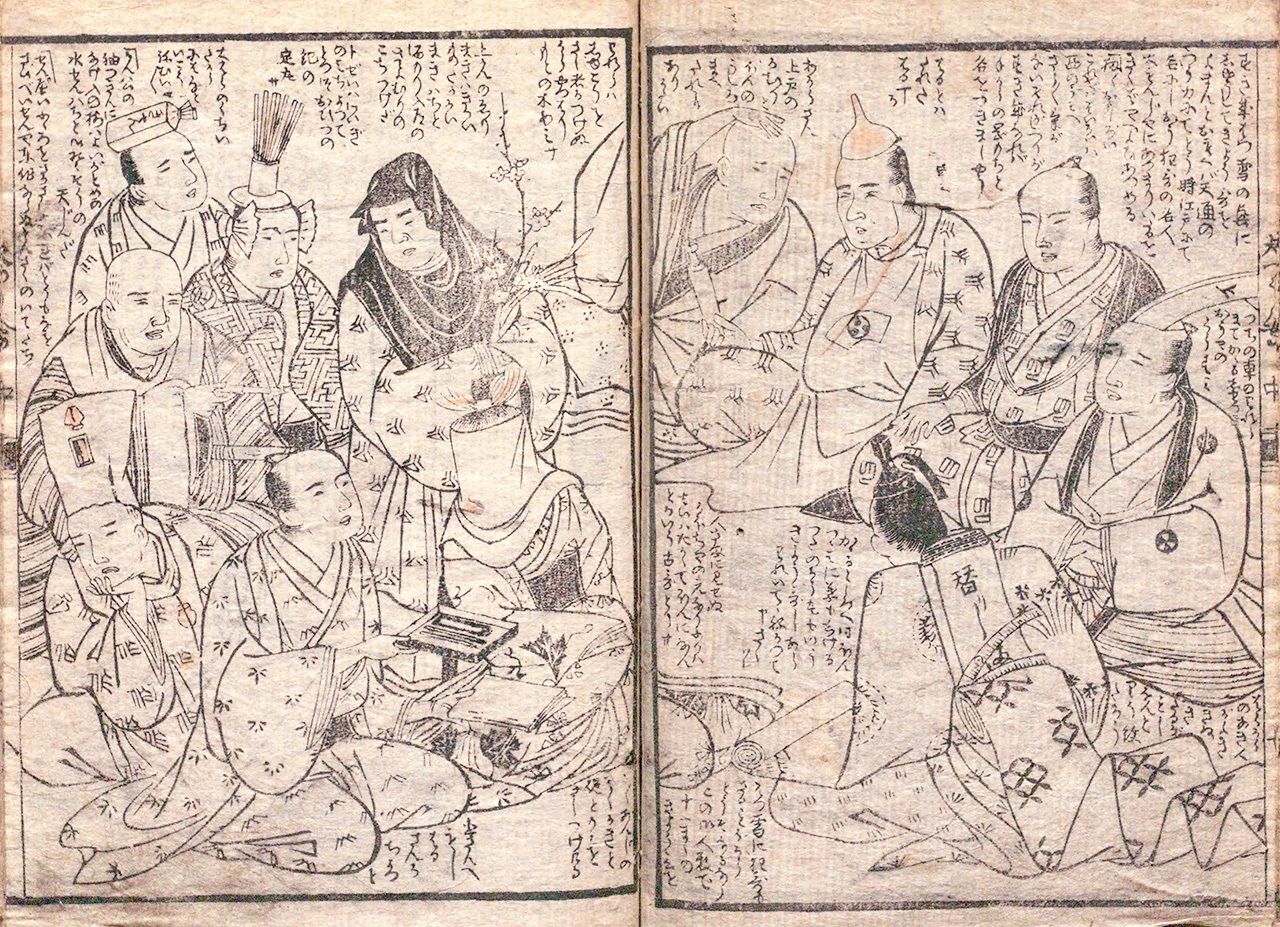

A picture in Yoshiwara daitsūe (Meeting of the Great Yoshiwara Connoisseurs) shows popular kyōka poets meeting together, dressed in costumes. Only Tsutaya (at bottom left) is dressed in an ordinary kimono. (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

Tsutaya made collections of kyōka by poets like Tegarano Okamochi, who also wrote fiction under the penname Hōseidō Kisanji, and Koikawa Harumachi, turning the books into hits. The two men were samurai, but Tsutaya was able to cross the strict class divide that existed in Edo-period Japan. He himself wrote kyōka under the name Tsuta no Karamaru, which fostered mutual respect with other writers.

In picture books, Tsutaya showed impeccable taste in the selection of artists like Katsushika Hokusai and Kitagawa Utamaro. Hokusai’s skill at depicting famous places and Utamaro’s realism added refinement to Tsutaya’s publications.

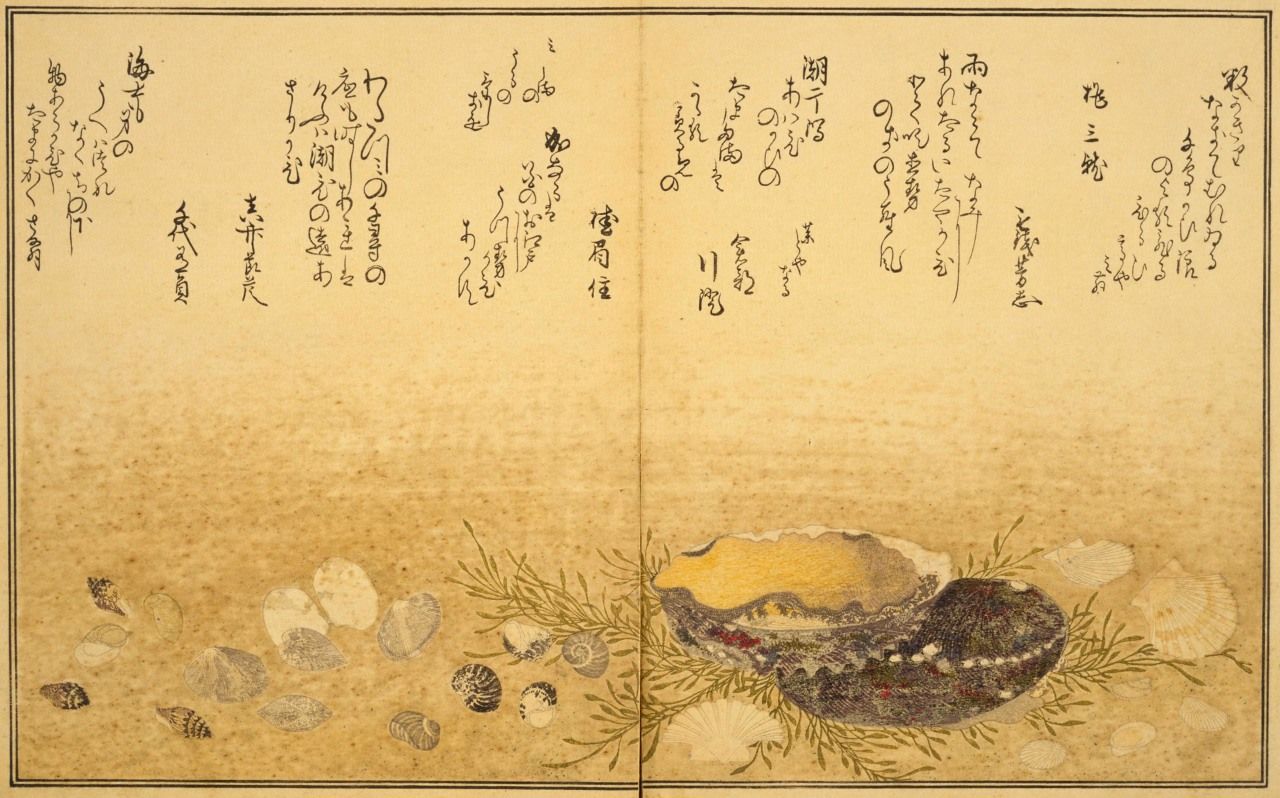

Ehon: Shiohi no tsuto (Picture Book: Gifts of the Ebb Tide) was a gorgeous publication with realistic illustrations by Utamaro, published in the late 1780s. (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

The covers of kusazōshi gave some indication to their content by their color, with red usually being for children and jōruri puppet theater and kabuki themed works coming in black or blue. Tsutaya was known for his yellow-backed kibyōshi, sophisticated, humorous works for adults that often had a satirical edge.

The best example may be the 1789 work Ōmugaeshi bunbu no futamichi (Parroting the Twin Paths of Literary and Military Arts) with text by Koikawa Harumachi and illustrations by Kitao Masayoshi.

The work came out during the Kansei Reforms (1787–93) led by Matsudaira Sadanobu, a chief senior councilor in the government who promoted thrift and discipline. Matsudaira also banned publications that took a frivolous approach to the issues of the time and ordered samurai to devote themselves to military training. Amid this austere atmosphere, the book boldly mocked samurai, including hinting that they “ride women” rather than horses and suggested that there were many who ignored the calls to frugality and spent all their time in idle amusement. Drawing the ire of the authorities, the author Koikawa was summoned by the shogunate and died shortly afterward, possibly by suicide.

Ōmugaeshi bunbu no futamichi is full of biting satire aimed at the samurai class. (Courtesy the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room)

In 1791, there was another crackdown, this time on sharebon, a genre that introduced topics like amusements for courtesans and customers in the pleasure quarters. Author Santō Kyōden was targeted by the authorities for corrupting public morals and made to wear manacles for 50 days, while his publisher Tsutaya had some of his assets seized.

Utamaro and Sharaku

Tsutaya, undaunted, moved on to his next moneymaker, heavily marketing Utamaro’s portraits of women. Fujin ninsō juppon (Ten Types of Feminine Demeanor) and Fujin sōgaku juttai (Ten Types of Feminine Physiognomy) showed close-up portraits of Edo’s women and attempted to characterize them through the fashionable pseudoscience of physiognomy. Some bared breasts added to the eroticism, and the series made Utamaro famous.

A women in Fujin ninsō juppon (Ten Types of Feminine Demeanor) casually blows a poppin, a kind of glass toy that makes a noise. Painted around 1792–93. (Courtesy ColBase)

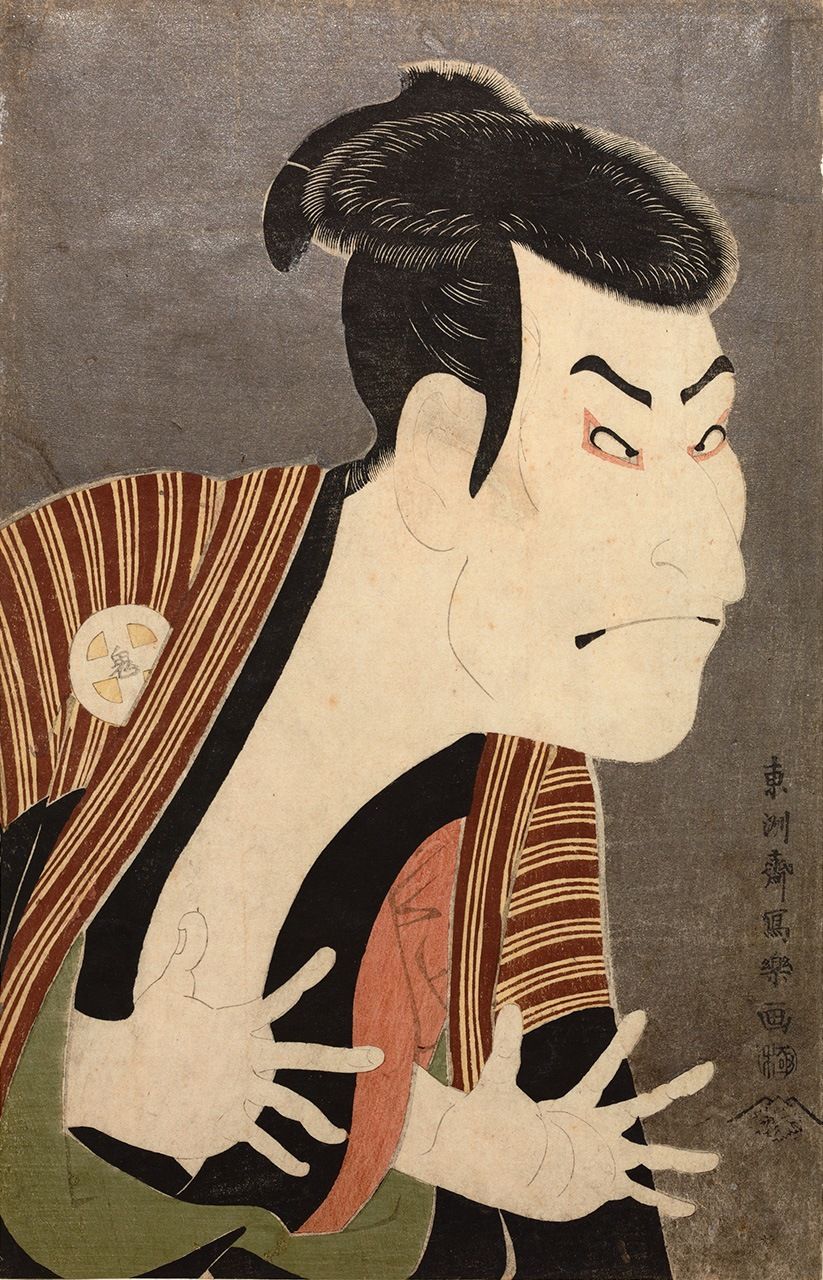

Tsutaya also discovered Tōshūsai Sharaku, an unknown artist who appeared on the scene in 1794. Sharaku created 140 portraits of kabuki actors and other artists over a brief 10-month span. Although the works were the equivalent of today’s celebrity photographs, Sharaku employed the ōkubie style that focused on the eyes and other features to convey a powerful impression, putting them a step above anything that had come before. Tsutaya, who had a monopoly on Sharaku’s creations, produced all the works.

Sharaku’s Sandaime Ōtani Oniji no yakko Edobei (Ōtani Oniji III as the yakko Edobei) is a classic kubie work. Edobei was a yakko or servant and also a robber in a kabuki play, showing a distinctive evil expression in this 1794 work. (Courtesy ColBase)

Sharaku was active for only a brief span, and nothing more was heard of him from early 1795 onward. Some suggest he was really a nō actor, but to this day his identity remains one of Edo’s greatest mysteries.

Matsudaira Sadanobu fell out of political favor in 1793, but the shogunate did not loosen its strict social policies. Perhaps the ongoing pressure by the authorities and the abrupt cease of Sharaku’s works led to a loss of creative drive in Tsutaya. In 1796, he collapsed from illness, and he died in May the following year at the age of 47 from what is believed to have been beriberi.

In a career of just over two decades, Tsutaya blazed a trail in the Edo publishing world. A memorial to him can be found at the temple Shōhōji in Asakusa, Tokyo.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image: Tsutaya Jūzaburō speaking at the beginning of Santō Kyōden’s Hakoiri musume men’ya ningyo. Courtesy the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room.)