The Yoshiwara Pleasure Quarters: A Cradle for Japan’s Edo Culture

History Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Yoshiwara, the name of the famous government-licensed pleasure quarters in Edo, today’s Tokyo, conjures up a range of images. Some may think of it as a place of flamboyant romantic culture, a setting for ukiyo-e prints by artists like Torii Kiyonaga and Kitagawa Utamaro, or a location that influenced the development of kabuki, traditional music, and fashion. For others, it was a place where procurers called zegen brought the daughters of poor households to be sexually exploited.

None of these images are mistaken, but they are each limited to a single perspective. A comprehensive view is needed to understand Yoshiwara, which was a “system of systems” comprising a complex relationship of multiple factors.

Idols and Fashion Leaders

In 1618, the shogunate established Yoshiwara in Edo around the same time as other licensed quarters in Kyoto (Shimabara) and Osaka (Shinmachi). At first close to what is now Nihonbashi, in 1657 it moved to Asakusa. Sometimes the two locations are distinguished, with the former being named Moto-Yoshiwara to denote it as “the original” and the latter Shin-Yoshiwara (New Yoshiwara). Often, though, they are simply put together as Yoshiwara. As well as brothels, the district had teahouses that introduced men to these establishments and ageya (houses of assignation) where high-ranking customers invited courtesans. In the mid-eighteenth century, however, the ageya disappeared in Edo.

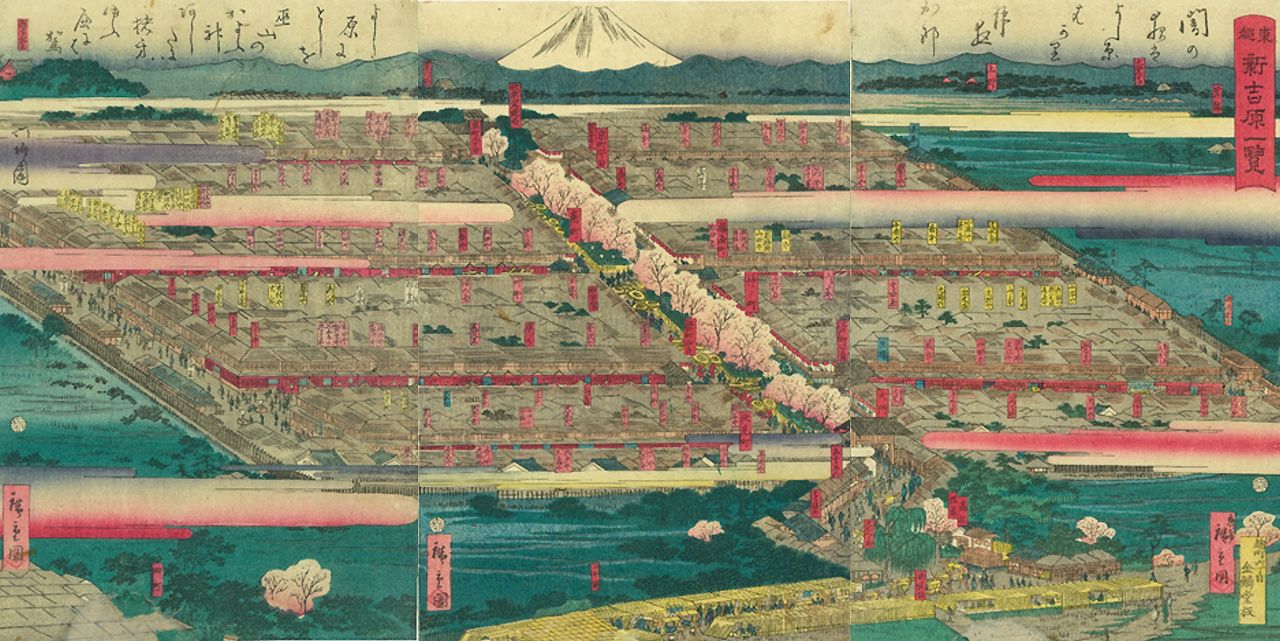

Hiroshige II, Tōto Shin-Yoshiwara ichiran (View of Shin-Yoshiwara in the Eastern Capital), 1860, private collection. The Yoshiwara district was around 266 meters long and 355 meters wide, surrounded by a moat, and generally only accessible by a large central gate. The Nakanochō main street, lined with cherry trees, had teahouses that mediated for the brothels.

Most of the prostitutes were girls from poor households who worked to pay back money given by the brothels to their parents. The system was irrational and took no account of whether the young girls were suited to sleeping with random male customers. While undeniably true, focusing on this point alone means only seeing one side of Yoshiwara. As values and ethics change over time, trying to understand Yoshiwara from a modern perspective can lead to great misinterpretations.

When Tokugawa Ieyasu aimed to develop Edo, one of his policies was to found Moto-Yoshiwara (now Nihonbashi Ningyōchō in Chūō). A similar way of thinking led to the establishment of the Recreation and Amusement Association to provide organized prostitution for the US occupying troops in Japan after World War II. The sankin kōtai system, whereby daimyō spent every other year living in Edo, meant large numbers of vassals were stationed in the city. As there were also many migrant workers, women were far outnumbered by men.

In the Edo period (1603–1868), there were a limited number of jobs that women could do, and earning a living as a mistress or a sex worker at Yoshiwara were seen as potential options. At the large establishments, it was possible to rise from kamuro (attendant girl) to a shinzō (apprentice) and then an oiran (the highest-ranking courtesan). At the age of 27, in the traditional kazoedoshi count—where people are considered to be aged one at birth, with one year added every New Year—women would reach the end of their service and, in the case of high-ranking courtesans, might gain their freedom via a proposed position as wife or mistress for a rich samurai or merchant.

It is difficult to imagine now how Edo citizens would feel to sleep with Yoshiwara courtesans. The artworks depicting them have been called the world’s most beautiful renderings of prostitutes, and the oiran pictures would have aroused the men of Edo like today’s pinup idols, while women imitated the courtesans’ hairstyles and fashions.

Keisai Eisen, Edochō itchōme, Izumiya-uchi, Senju (Senju from Izumiya, Edochō Itchōme), 1821, private collection. The complex hairstyle with many kanzashi ornaments and a bewitching kimono made courtesans fascinating for women too. The small writing in the title at upper right gives the names of the kamuro (attendants), Shikano and Kanoko.

A Center for Refined Cultural Exchange

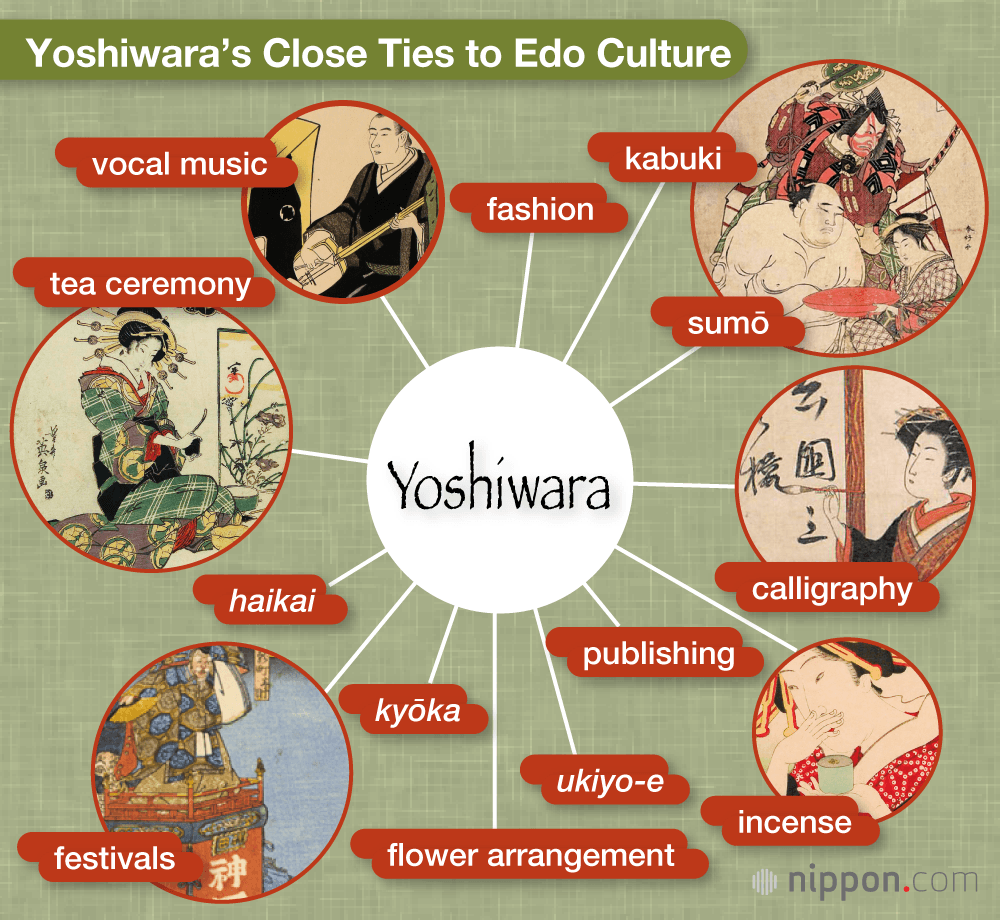

As Japan’s most famous pleasure district, Yoshiwara was notable for providing the foundations of Edo-period culture. It influenced a huge range of arts and disciplines, including kabuki, vocal music, flower arrangement, kyōka (comic poetry), haikai poetry, the tea ceremony, fashion, ukiyo-e, publishing, festivals, incense, calligraphy, and sumō.

Until the Meiji Restoration, owners of large Yoshiwara brothels supported cultural activities like poetry, vocal music, and noroma puppet theater, and acted as patrons of kabuki actors. They also trained the women of pleasure, as the oiran who catered to high-ranking samurai and wealthy merchants needed to be culturally sophisticated. The elite oiran, however, only accounted for 2% of the estimated 3,000–5,000 prostitutes in Yoshiwara.

I would like to give an example of the refined interactions between oiran and customers. The painter Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1829) was the younger brother of the leader of the Himeji domain. He bought the freedom of the courtesan Kagawa from the Daimonjiya brothel and honed his art at his Ugean (Rain Flower Hermitage) studio in Negishi (now in Taitō, Tokyo). He was also a patron of kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjūrō VII, and was skilled at composing haikai and kyōka poetry. Hōitsu’s witty conversations with high-class prostitutes were written down by the owner of the Chūshuntei restaurant near Yoshiwara and published in the collection Kandan sūkoku (Hours of Casual Conversation). Below is an exchange with Ōyodo, an oiran from the Tsuruya brothel.

A regular customer of Ōyodo heard that Hōitsu also sometimes visited her, and became jealous that they might be close. When the rumor reached Ōyodo, she wrote the poem, “These days, the pond is muddied by early summer rains,” and showed it to Hōitsu. This played on the second character in her name (淀), which could mean “pond,” while the phrase “muddied the pond” also suggested a loss of reputation.

きのふけふ淀の濁や皐月雨

Kinō kyō / yodo no nigori ya / satsukiame

These days, the pond is muddied by early summer rains.

Hōitsu responded with his own poem, “The pond’s koi have not been savored in the early summer rains.” While developing the themes of her poem, its puns produce an alternative reading with koi meaning “carp”—noting that Ōyodo “had yet to sample the carp of Osaka’s Yodo River,” said to be the finest in the land, or in other words did not know the subtleties of love.

淀鯉のまだ味しらずさ月雨

Yodokoi no / mada mishirazu / satsukiame

The pond’s koi have not been savored in the early summer rains.

Ōyodo countered with another poem, “It’s hard wearing a kimono drenched by the early summer rains.” This refers to a common idiom where “wet clothes” indicate false charges. The two of them laughed together and drank sake in the Masuya eel restaurant.

ぬれ衣を着る身はつらし皐月雨

Nureginu o / kiru mi wa tsurashi / satsukiame

It’s hard wearing a kimono drenched by the early summer rains.

Hōitsu wrote lyrics for katōbushi songs accompanying dances at the major festivals (Tenka Matsuri) associated with Kanda Myōjin Shrine and Sannō Gongen (now Hie Shrine). The tunes for these were composed by male geisha, who were high-class musicians in Yoshiwara. Male geisha also created music to accompany kabuki. They took the work songs and comic songs of the migrant workers who came to Edo and rearranged them into sophisticated nagauta.

As well as being a center for social and artistic exchange, Yoshiwara acted as the cradle for Edo culture.

Utagawa Kunisada II, Yūri hakkei, Shin-Yoshiwara Kakusenrō-uchi Itsumiki (Eight Scenes, Courtesans from the Pleasure Quarters: Itsumiki from Kakusenrō, Shin-Yoshiwara), 1869, private collection. An unusual landscape format picture of a courtesan. The moon shines above Nakanochō and the great gate.

A Cultural Transformation

The Kandan sūkoku collection also introduces Wakamatsuya Tōemon, a brothel owner who treated with consideration the prostitutes who worked for him in the early nineteenth century.

The book says that when the prostitutes went out into Yoshiwara’s main Nakanochō street to find customers, Tōemon greeted them and rang a bell. Even if they returned alone, he would repeat the ritual. When the cashier reported that sales had reached three ryō (in the currency of the time), the establishment closed for the day, even if there were prostitutes lined up in the harimise, a room in the front of the brothel where customers could see them through a lattice front. Tōemon said that was enough money to make a living, so he did not overwork them, and if the brothel did not make three ryō, it always closed at ten at night. Clothes were ordered as cheaply as possible from the Okadaya store, so the girls did not have to go into debt to buy them.

When fires broke out, and the prostitutes had to evacuate to the temple Daionji, Tōemon’s father Uemon had let them go through his house and calmed them with tea and water.

The book continues by saying that there was no physical punishment for misbehavior. If the prostitutes did not initially listen to admonishment, they would all do so on the threat of being transferred to another establishment. If their parents needed money, the brothel would lend it to them. These payments were gradually returned, but the length of service of the prostitutes was not extended, and sometimes part of the debt remained unpaid in the end.

Naturally, treatment of sex workers varied with the size and nature of the establishment, and some owners were exploitative and physically abusive. The above account shows, however, that there were also friendlier owners like the two Wakamatsuya generations.

Ochiai Yoshiiku, Kakusenrō, 1863, private collection. The artwork depicts the glamorous courtesans of the Kakusenrō brothel.

The enactment of an ordinance liberating all geisha and prostitutes in 1872 brought a cultural transformation to Yoshiwara. The abolition of public prostitution, prohibition of human trafficking, regulation of service contracts, and cancellation of debts meant that 20 large brothels had to close. Establishments that hired prostitutes by giving sums of money that had to be repaid must have faced a shortage of capital. Although prostitutes were said to continue to work of their own volition, the entry of many smaller brothels meant that the strict customs of the Edo period were lost. The cultural standing of Yoshiwara could no longer be maintained, and the area became simply a place of exploitation of both sex workers and customers.

In the fervor for Westernization of the Meiji era (1868–1912), Yoshiwara’s traditional music was rejected as out of step with modernization. The end finally came with the Anti-Prostitution Act of 1957, and Edo Yoshiwara culture was entirely extinguished. The area today is like an unknown location that nobody teaches about, forgotten and disowned.

Yoshiwara went through great changes through the two and a half centuries of the Edo period. From the Meiji era onward, government policies and the national mood brought radical shifts to brothel management, the position and treatment of prostitutes, and the cultural atmosphere. Now the dissipated image of late Meiji, as seen in the adult film Yoshiwara enjō (Tokyo Bordello), is dominant, while the witty cultural exchange enjoyed by Hōitsu and more benevolent brothels like Wakamatsuya are forgotten. Without Yoshiwara, it is impossible to understand Japan’s distinctive Edo culture. To pass this on to future generations and people overseas, comprehensive reappreciation of Yoshiwara is urgently required.

(Originally published in Japanese on June 18, 2020. Banner image: Ochiai Yoshiiku, Kakusenrō, 1863, private collection. The artwork depicts the glamorous courtesans of the Kakusenrō brothel.)