Japanese Identity and Christianity on the Banks of the Ganges: Endō Shūsaku’s “Deep River”

Books Culture Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Globe-Trotting Exploration of Faith

The plot of Endō Shūsaku’s final novel, Fukai kawa (translated by Van C. Gessel as Deep River), follows a group of Japanese tourists on a trip to India, each with their own struggles and problems. One of the main characters is Mitsuko, who works as a volunteer in a hospital. Another central figure is Ōtsu, who became a Christian under his mother’s influence and has a vocation for the priesthood.

Mitsuko and Ōtsu were once university students together. Mitsuko, who feels herself incapable of really loving a person, decides to seduce the pious Ōtsu out of a spiteful desire to ridicule his religion. Ōtsu soon starts to imitate Mitsuko’s habit of referring to God as his “Onion,” and vows to give up his faith. But after Mitsuko ends the affair, he travels to France and enters a seminary to study for the priesthood. Later, the pair meet again when Mitsuko visits France, spending a few days away from her new husband to visit Ōtsu during her honeymoon. When she reminds him of his vow to give up his faith, he starts to talk with feeling about Christ:

“After you snubbed . . . I began to understand . . . just a little the sufferings of the man who was rejected by all men. . . . and I heard a voice, saying ‘Come to me. Come, I was rejected as you have been. So I will never abandon you.’ That’s what the voice said.”

His behavior makes no sense to Mitsuko. “You’re Japanese, aren’t you? It makes my teeth stand on edge just to think of you as a Japanese believing in this European Christianity nonsense.”

But Ōtsu insists: “I don’t believe in European Christianity.”

He explains: “For three years I’ve lived here, and I’ve tired of the way people here think. The way of thinking that they’ve kneaded with their own hands and fashioned to meet the workings of their own hearts. They’re ponderous to an Asian like me. I can’t blend in with them, and so every day is hell for me. When I try to tell some of my French classmates or teachers how I feel, they admonish me and say that the truth knows no distinctions between Europe and Asia.”

Ōtsu comes to be regarded as a heretic by his fellow seminarians and moves to India, where he enters a monastery near the Ganges. Mitsuko’s marriage soon falls apart, and hearing rumors that Ōtsu is in India, she decides to join a tour there after her divorce in the hope that she might find him.

The All-Encompassing River of Love

The Japanese tourists make their way to the holy city of Benares (referred to in the novel by its modern name of Varanasi), on the banks of the mighty Ganges. The ancient city is one of the holiest of all Hindu sites, and also holds a special place in Buddhism, as the setting of the Buddha’s first sermon, at nearby Sarnath. Along the banks of one side of the river, backed by the ancient temples and warren-like streets of the old city, are the famous step-like “ghats” that lead down to the holy waters. The ghats are thronged with people throughout the day, alive with activity as pilgrims come to immerse themselves in the holy river. The river is also home to two “burning ghats” where the bodies of the dead are cremated on the steps of the river and their ashes returned to Mother Ganges. Life and death exist side-by-side on the banks of the holy city.

Ōtsu is eventually asked to move on from his Indian monastery as well, and spends his days with Hindu pilgrims, helping to carry the bodies of the penniless dead to the burning ghats. And there one day he meets Mitsuko again.

Talking about the path his faith has taken, Ōtsu says, “In the end I’ve decided that my Onion doesn’t live only within European Christianity. He can be found in Hinduism and in Buddhism. This is no longer an idea in my head; it’s a way of life I’ve chosen for myself.” To which Mitsuko can only respond, “But you’ve pulled the rug out from under your own life.”

The Japanese tourists are still in India when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi is assassinated. Shortly after the news breaks, Ōtsu speaks to Mitsuko about the tragedy in the following terms:

“When all life has been drained from them and their bodies are enshrouded in flames, I say a prayer to my Onion. ‘This person I’m handing over to you,’ I pray, ‘please accept and enfold him in your arms. . . . Every time I look at the River Ganges, I think of my Onion. The Ganges swallows up the ashes of every person as it flows along, rejecting neither the beggar woman who stretches out her fingerless hands nor the murdered prime minister, Gandhi. The river of love that is my Onion flows past, accepting all, rejecting neither the ugliest of men nor the filthiest.”

Eventually, Mitsuko comes to feel something of the universal power of the Ganges: “There’s still the river . . . It’s a deep river, so deep I feel as though it’s not just for the Hindus but for everyone.”

Perhaps these lines contain a hint of the message Endō hoped to convey with this novel. God is like the Ganges, embracing and encompassing everything. It makes no sense to reject other religions, or for different faiths to fight just because they are following a different path to the same end. The God of Christianity is not the one unique and supreme deity, but one who coexists along with numerous other gods, like the myriad kami of Japan’s Shintō faith. Something close to this may have been what the author was proposing as a more “Japanese” version of Christianity.

Living On After Death

Another major subject concern of the novel is reincarnation: the belief that all living things, including human beings, experience many lives, and are reborn in another body after they die. No doubt this was a subject of personal interest for the author as his life and work entered its final chapter. But as a Christian author, Endō seems to perceive the term in the light of Christ’s resurrection. He seems to see reincarnation not as a literal act of rebirth in another body, but rather of the soul living on after death in the hearts and minds of other people.

In the first chapter of the novel, a man named Isobe loses his wife to cancer. Shortly just before she dies, his wife whispers to him: “I know for sure . . . I’ll be reborn somewhere in this world. Look for me . . . find me . . . promise!” Isobe eventually joins the tour to India hoping to find a child who might be the reincarnation of this Japanese woman. Mitsuko, who is working as a volunteer with terminal cancer patients at the hospital where his wife spends her last weeks, ends up joining the same tour.

As the tour comes to an end and Isobe has still not found his wife’s reincarnation, Mitsuko consoles him with the words: “At the very least, I’m sure your wife has come back to life inside your heart.” In a separate scene, Ōtsu says to Mitsuko: “Look at me: he [Jesus] is alive even inside a man like me.”

Toward the end of the novel, the author writes:

“The Onion had died many long years ago, but he had been reborn in the lives of other people. Even after nearly two thousand years had passed, he had been reborn in these nuns, and had been reborn in Ōtsu.”

The story ends rather abruptly, rather as if the television has suddenly turned off before the program has reached the end. Perhaps the author was deliberately seeking to create a parallel with the surprising first pages of the story, which open with the incongruous cries of a sweet potato seller hawking his wares: “Yaki imo-o. Piping hot yaki imo-o.” The novel also contains numerous reminders of the mischievous side of the author, who wrote popular light “entertainments” alongside his more contemplative works. The in-joke references between Ōtsu and Mitsuko to God as “the Onion,” for example, help to lighten the mood, pulling readers in and getting them to consider the serious subjects at the heart of the story. They also serve to make the novel accessible to as broad a readership as possible—Endō never forgot the novelist’s duty to entertain as well as enlighten.

I once met someone who accompanied Endō on a research trip to India as he prepared to write what became his final novel. Endō was nearly 70 at the time, and his health was already failing, but nevertheless he insisted on staying in cheap hotels to experience the “real” India, despite the punishing heat. The person I spoke to described him sitting calming on the steps near the burning ghats, intently watching the scenery unfold before his eyes.

Perhaps the response he felt to what he saw there is reflected in this passage from Deep River, where one of the protagonists sits in the same spot and gazes contemplatively at the holy river.

“Naked men and woman stood in array, their bodies exposed to the rosy light of the morning sun as they filled their mouths with the water of the Ganges and joined their hands together in prayer. Each had their separate lives, the secrets they could relate to no one else, secrets which they carried as heavy burdens upon their backs as they lived out their existences. Each had something that needed cleansing in the River Ganges.”

A century on from his birth, Endō Shūsaku continues to be reborn in the hearts and minds of his many readers today, both in Japan and around the world.

This and all subsequent quotes are taken from the English translation by Van C. Gessel, which is available in searchable form on the Internet Archive.

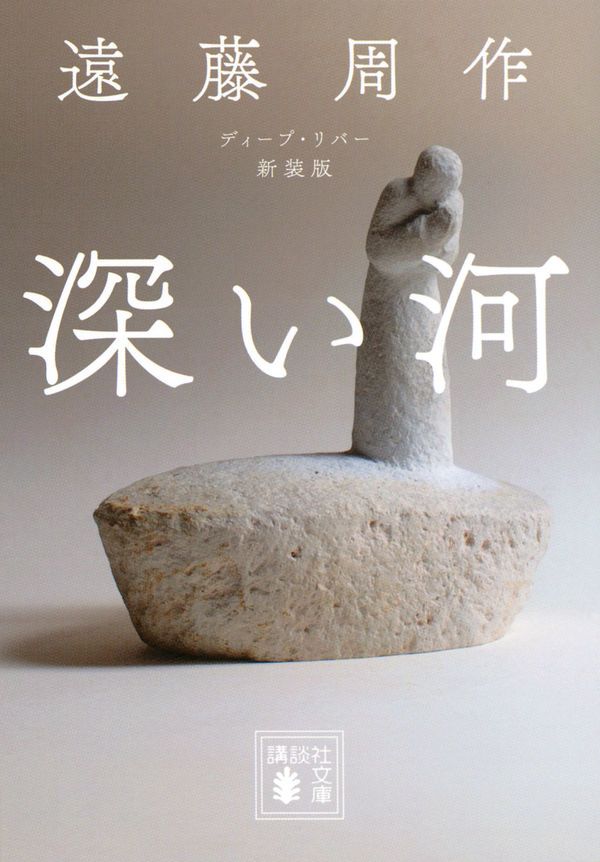

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Fukai Kawa. © Kōdansha.)

literature book review Christianity India Endo Shusaku Ganges River