“Light Rains Sometimes Fall”: Nature in Pandemic London Via the Prism of Japan’s 72 Microseasons

Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Years ago, when I started studying Japanese, the first full phrase I learned was “Ame ga yoku furimasu, ne” which means, “It rains a lot, doesn’t it?” I was living in England at the time (as I do now), and actually we don’t get many Japanese-style torrential downpours here. Rather, we get rained on sporadically: light showers, scattered showers, drizzle, mizzle, and more.

Hence, no doubt, the title of Light Rains Sometimes Fall: A British Year Through Japan’s 72 Seasons, a new book by English nature writer Lev Parikian.

“Light rains sometimes fall” is the fifty-third season in the traditional Japanese calendar and, coincidentally, when Parikian and I meet near his London home. He tells me how he had no special interest in Japan before writing his book, but stumbled across a list of the 72 seasons on the internet. Fascinated, he also downloaded a popular app on the Japanese traditional calendar. He had found his next book project.

“The idea of breaking the four big sweeping seasons into more manageable chunks was very enticing,” Parikian says. “It was a springboard for a different way of looking at things.”

And he did a lot of looking. The book is a diary of nature observations covering the period from February 2020 to January 2021, when the COVID-19 pandemic was raging in Britain and London was in and out of strict lockdown.

The pandemic had made Parikian’s main occupation as a conductor “instantly redundant,” he says. A daily walk in his local area was a precious chance to get outside, and a vital distraction and consolation.

“With the world turned upside down, nature was something that was reliable,” he recalls.

Parikian stresses that he didn’t want to write “a pandemic book.” But those events undeniably affected both his own and others’ interactions with nature. He recalls how some people told him how “loud” birdsong had become after lockdown muted the London traffic.

Ironically, the period was one of the best chances to explore urban nature in living memory. Many people were either working from home or on furlough with plenty of free time to pay attention. And the first major COVID peak coincided with a glorious long spell of dry and sunny weather in much of England.

At the time, there were strict restrictions on how far people in England could travel. But that mattered little to Parikian, because the book is about the nature on our doorsteps. He makes his nature observations in his house, garden, local streets, the park, and especially on his daily stroll through the West Norwood Cemetery, a sprawling and wild Victorian necropolis.

Bears Start Hibernating—in London?

Parikian’s book is structured as 72 essays, one for each microseason. But rather than using the names of the Japanese microseasons, he devised his own London equivalents. In any case, many of the Japanese seasonal markers would be hard to find in the London metropolis.

As Parikian quips, “’Bears start hibernating’ is not something that you are going to come across much in West Norwood.”

In the book, the London version of that season (December 12–16) is “Grey skies are unremitting.” (Anyone who has endured one of London’s dreich winters will understand.) Meanwhile, the chapter that covers the Japanese microseason of “Light rains sometimes fall” includes a startling encounter in Parikian’s shed. Looking for a tool, he stumbles on and tentatively identifies a false widow spider. Hence, the chapter title becomes “Spiders appear in sheds.”

Having lived in both Japan and Britain, it was hard to read this book without musing on other differences in natural environment. In fact, one of the more puzzling questions I was occasionally asked in Japan was, “How many seasons does England have?“ Presumably, these questioners believed Japan was special, if not unique, for having four seasons. I tended to take umbrage. Of course we also have four seasons!

But it’s a reasonable question. As Parikian points out in his introduction, Thailand has three seasons: hot, cold, and rainy. The Hindu calendar has six: the same four as in Japan and Britain plus the monsoon and an extra winter. The American writer Kurt Vonnegut reckoned that the eastern seaboard of the US also has six: unlocking, spring, summer, autumn, locking, winter.

And while both Britain and Japan do share four seasons, Japan’s are much more sharply defined—crystal clear winter skies, spring cherry blossoms, scorching summer, crimson autumn. So defined, perhaps, that ancient Japanese felt the need to subdivide them and subdivide again into the traditional 72.

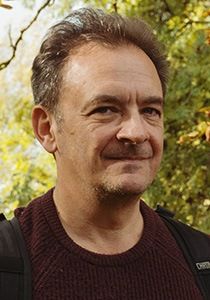

Lev Parikian takes a break during his daily walk in the cemetery near his home.

On the other hand, while Britain has some wintery frosts and golden summer evenings, the seasons tend to be what Parikian calls “sprawling.” They overlap, intermingle, and seem to get less distinct each year. Recently, snow has been replaced by winter floods, and our summers seem to be getting both hotter and wetter.

Like the pandemic, climate change also lurks behind Parikian’s light-hearted observations. He notes that the Japanese snowy microseasons could have applied to London even just a few decades ago. Today, you are almost as unlikely to encounter the snow-shrouded London of Dickens as a Conan Doyle pea soup fog.

“Climate change was something I was very aware of,” he says. Yet, he stresses that his priority in writing the book was to enthuse people about nature. “It is not that I am not deeply troubled by climate change, but everyone has a different approach to writing about it.” After all, people need to care about something before they seek to protect it.

“Look Again and Look Better!”

Parikian grew up in rural Oxfordshire but has lived in cities for most of his life. He was in his mid-forties when he rediscovered his love of nature. That started with birds, which are still his main interest, and he clearly draws on a vast knowledge. (At one point in the book he casually mentions identifying the songs of 23 species in the dawn chorus.) But he’s also fascinated by moths, butterflies, mammals, insects, trees, and much more.

He writes as someone who is learning about nature and bringing the reader along on his journey of discovery. And the book is full of astonishing discovery. (It took me a while to read as I was constantly putting the book down to check Wikipedia and Google images. What does chicken-of-the-woods fungus look like? Did prehistoric dragonflies really have 75-centimeter wingspans?)

Meanwhile, Parikian implicitly poses two more fundamental questions: “What exactly is nature?” and “Where can we find it?”

The author takes a broad view. He notes that a tomato plant in a pot might be considered nature, or even the angle and quality of the light as it strikes an urban building. He writes about weeds in the pavement and spiders in his shed. In other words, nature is everywhere where we are. And it doesn’t matter if you live in a London suburb, wander lonely as a cloud in Wordsworth’s Lake district, or frequent a Heian era Japanese garden.

“Setting nature apart is understandable,” says Parikian. “But nature is not something separate. We are part of it, and it is part of us.”

Parikian says he wanted his book to be more than just passively read. Several people have told him that they will read the book in “real time,” one microseason at a time. This strikes me as a great idea—a personal journey of discovery, and a way to hone your own powers of nature observation.

What will you find in your own neighborhood? Perhaps far more than you expect. After all, you don’t have to be a David Attenborough to pay a little more attention to the floofy (to use one of Parikian’s favorite words) visitors to the garden bird feeder or your local park.

As Parikian writes, “There’s a lot more out there than anyone sees, and you can’t see without looking . . . look, look again, look better.“

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: Author Lev Parikian walks through London’s West Norwood Cemetery. All photos © Tony McNicol.)

Light Rains Sometimes Fall: A British Year Through Japan’s 72 Seasons

By Lev Parikian

Published by Elliott & Thompson (September 2021)

ISBN: 978-1783965779