Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s Shanghai Journal Brought to Life in New NHK Drama

Culture Arts Entertainment History Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

During the early decades of the twentieth century, from the end of the Meiji era (1868–1912) into the early years of Shōwa (1926–89), the district of Tabata in northern Tokyo became a kind of stronghold for original thinkers and artistic misfits, and was home to numerous young people with dreams.

In the years that followed, their names took the Japanese literary and artistic world by storm. Prominent figures who lived in the district included the writers Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, Murō Saisei, and Kikuchi Kan and the scholar Okakura Kakuzō, whose Book of Tea made him internationally famous, as well as painters like Takehisa Yumeji and Oana Ryūichi. Today, these famous names live on in the history books, but the places they knew have vanished over the course of a century of dramatic change. Only the Tabata Memorial Museum of Writers and Artists stands today as a reminder of the area’s past as a center of the Japanese intellectual and artistic world.

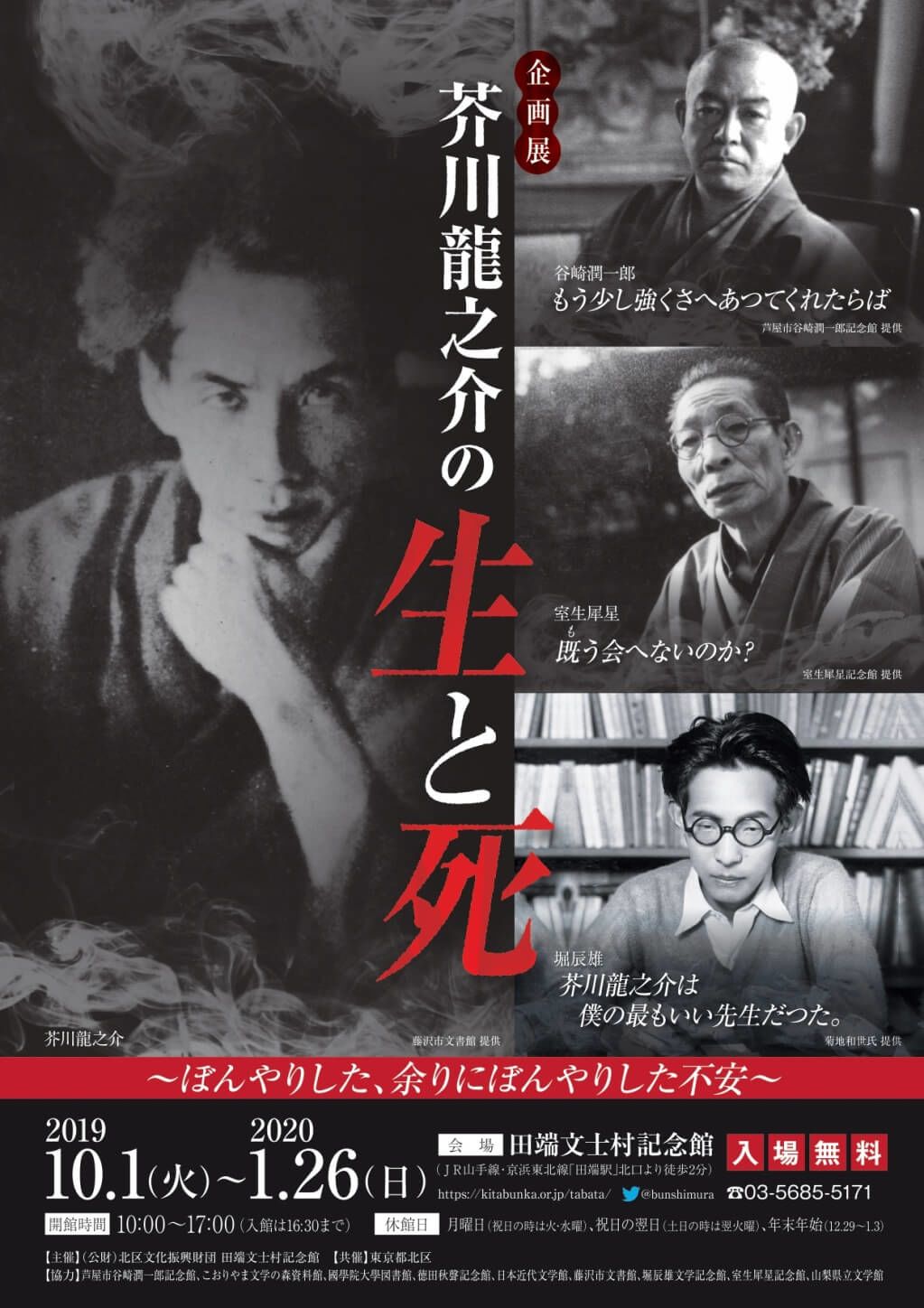

Since October 1, the museum has been running an exhibition titled “The Life and Death of Akutagawa Ryūnosuke.” One of the highlights of the exhibition is the author’s original handwritten manuscript of the first six pages of Shanghai yūki, Akutagawa’s account of his journey to China in 1921.

The Writer’s Ties to China

Readers in China, like readers around the world, know Akutagawa best for fantastic stories like “Rashōmon” and “Jigokuhen” (trans. “Hell Screen”), full of enchantment and madness. Akutagawa had a life-long interest in Chinese literature, and was particularly influenced by Tang-dynasty legends and tales of the uncanny and miraculous (Zhiguai xiaoshuo) from the Qing period. Of the 140 or so works he wrote over the course of his short life, 12 drew on Chinese sources.

In 1921, Akutagawa traveled to Shanghai as a reporter (or “overseas observer”) for the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun newspaper. He spent a little over 120 days traveling in the country, visiting Nanjing, Jiujiang, Hankou, Changsha, Luoyang, Datong, Tianjin, and Shenyang. He witnessed conditions in the country during the first decade of the Republic of China, a period of turmoil and revolutionary change as the “old empire” of the Qing entered the modern age. It was a moment of transformation that affected politics, culture, economy, and the customs of the people. Akutagawa discussed all these subjects, along with his personal travel experiences in Shanghai.

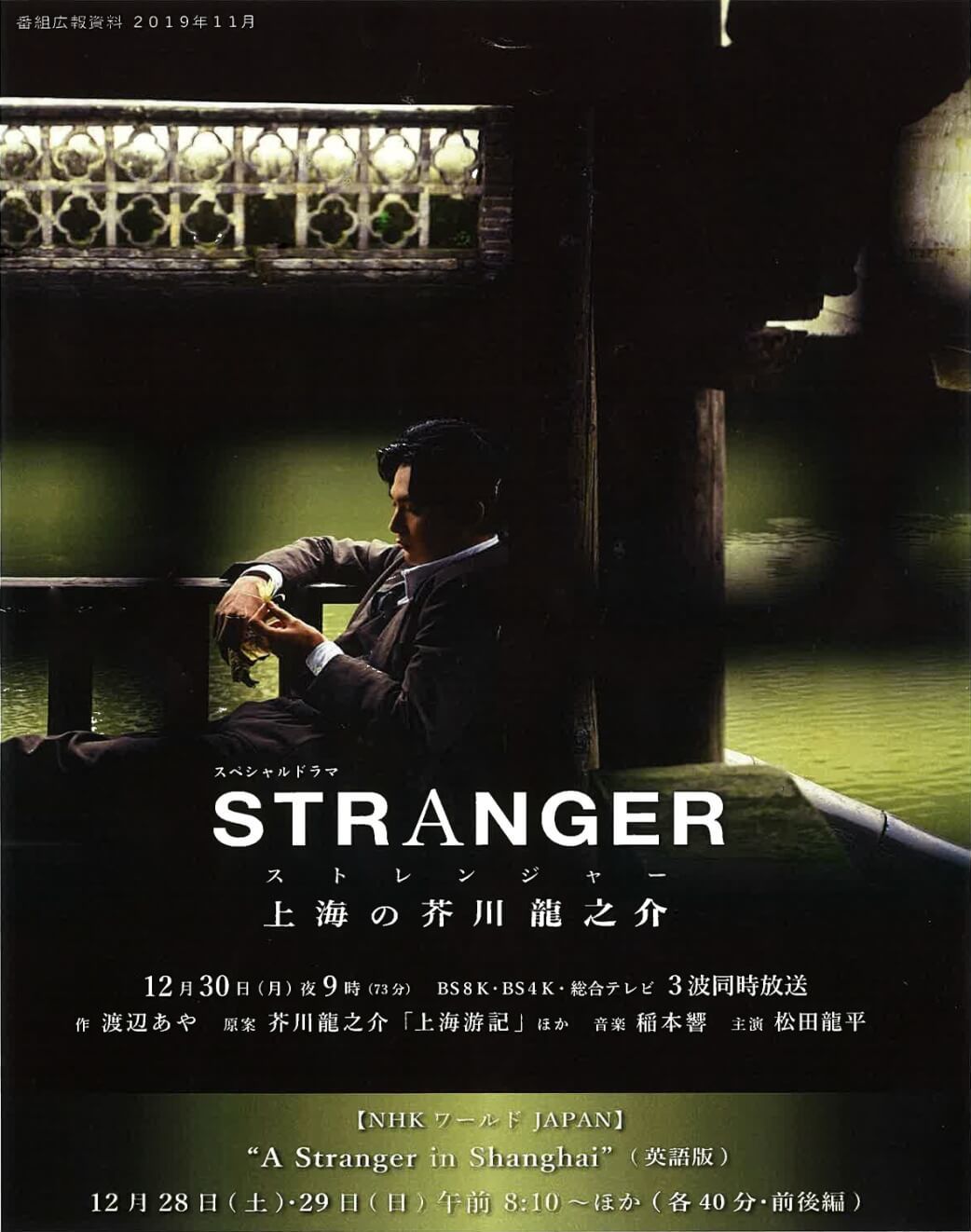

I seem to have some special connection with Akutagawa recently. On November 27, just a few days after I visited the exhibition in Tabata, I happened to receive an invitation to attend a preview screening of A Stranger in Shanghai at the NHK Broadcasting Center. NHK has used state-of-the-art high-resolution images to bring the “magical city” of Shanghai 100 years ago back to vivid life. (In fact, even this nickname derives from a Japanese source: Muramatsu Shōfu’s novel Mato, based on his experiences in the city in 1923.)

A Stranger in Shanghai airs in English in two parts on NHK World Japan. Tune in at 8:10 in the morning on Saturday and Sunday, December 28 and 29, 2019. The English and Chinese versions of the program will be streamed online beginning in January 2020.

Most of the filming was done in China, with a largely Chinese cast and crew (180 people, or 90% of the total). The production is based on exhaustive research and painstaking attention to detail. For example, Inamoto Hibiki used a 100-year-old piano for the film’s soundtrack, while Matsuda Ryūhei, who plays the part of Akutagawa, wears clothes made by Tsuge Isao using authentic tailoring techniques from the time.

Aghast at a Fallen China

In the film, Akutagawa can’t hide his disappointment in the face of what modern China has become. From the moment he disembarks in Shanghai, he is confronted by thieving rickshaw drivers and grasping old women selling flowers. “What is there in modern China? Politics, scholarship, the economy, art . . . everything is degraded and decadent. In art, can the country boast of a single work of true merit since the rule of the Jiaqing and Daoguang emperors? Yet the people, old and young alike, are idle and complacent. It is true, I suppose, that some energy and vitality can be discerned among the young. But the fact is that even their voices lack any great passion that might resound in the breasts of the entire people. I do not love China. I could not love it even if I wanted to.”

In his eyes, the fallen state of modern China was symbolized by an experience he had at the Chenghuang Temple in the heart of old Shanghai. In front of the temple was a lake, at the side of which stood a Chinese man, urinating. “That expanse of lake covered in sickly green, and the streaming arc of piss as it poured into the lake at an angle . . . this is more than a bittersweet picture of melancholy. It is a bitter symbol of what has become of the grand old empire.” From his reading of Chinese novels, Akutagawa was familiar with stories of libertines and Taoist immortals who had disguised themselves as beggars, but the reality was more than he had bargained for. The site of an actual Chinese beggar he finds “almost frightening in his extreme romanticism, scratching and licking at the rotting flesh of his knee like a man picking at a pomegranate.”

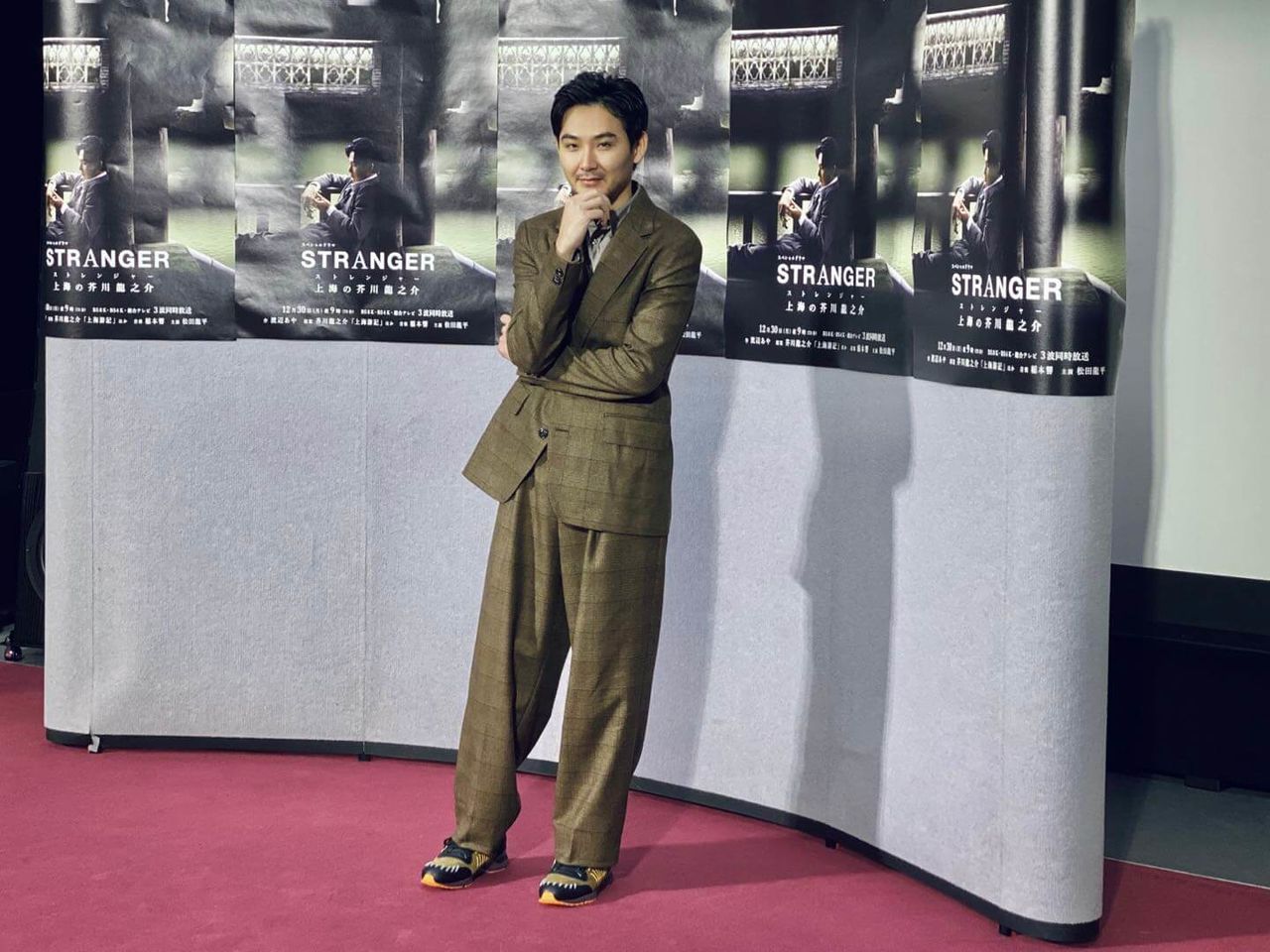

Matsuda Ryūhei at the preview screening of A Stranger in Shanghai.

Image courtesy of NHK.

The film is quite faithful to the details of Akutagawa’s account, and brings to vivid life many of the scenes and personages who appear in Shanghai yūki. The reenactments of Akutagawa’s visits to the Chinese theatre do justice to the colorful descriptions in his own account. Lumudan (Green Peony), the actor who played the famous female part of Su San in the play Yutang chun (Spring in the Jade Hall), appears on screen in elaborate makeup and makes an unforgettable impact, just as he did when Akutagawa met him after a performance: “He elegantly pushed back the sleeve of his red robes, embroidered with silver thread, and pinched his nose between his fingers before sending a thick clot of snot to the floor.” Lumudan was the stage name of the young Xun Huisheng, still a teenager at the time; he later became one of the four great actors of female roles in the Peking Opera.

We also meet the scholar Zhang Binglin (also known as Zhang Taiyan) just as he is depicted in Akutagawa’s account: with his narrow eyes, sallow complexion, and spindly beard, a stuffed crocodile displayed on the wall of his study. Another prominent figure is the Qing dynasty diplomat and statesmen Zheng Xiaoxu, still a vigorous figure in his old age, with his ruddy complexion, straight-backed posture, and air of genteel poverty. Akutagawa finds him living in a three-story building surrounded by bamboos and fragrant flowers. “I would be happy to accept poverty myself if it looked like this,” he writes.

The drama also introduces us to the beauties and courtesans whose company Akutagawa enjoyed at the Xiaoyoutian teahouse in Shanghai. Akutagawa sings the praises of these South China beauties, and is particularly smitten by their delicate ears. He writes “In fact, I came to feel not a little respect for the ears of these Chinese women.” In this regard, he writes, Japanese women cannot compete: “Japanese women’s ears are too flat and in many cases the flesh is too thick, making their ears look almost like mushrooms that have sprouted on the side of their face.” He suggests this difference is due to a process of evolution: Japanese women have always kept their ears hidden behind their thickly oiled elaborate hairstyles, while the ears of Chinese women have been left exposed to the fresh spring breezes.

Image courtesy of NHK.

Lessons to Bring Back Home

Akutagawa’s trip to Shanghai not only made him aware of the tumult of chaos and change in the young republic. It also changed the way he saw his own country, and even gave birth to a degree of antiwar feeling. Particularly important in this regard was the conversation he had with Zhang Taiyan.

Akutagawa was astonished when Zhang told him that the Japanese he hated most was the well-known fairytale hero Momotarō. “Momotarō is an abhorrent character. Together with his pheasant, dog, and monkey he goes off to conquer and subjugate the neighboring island of Onigashima, or demon island. Do the demons living there not have a right to their own lives? They are living and working in peace, minding their own business until Momotarō comes along . . .” Akutagawa was astonished by this take on the familiar story.

One aspect of this story that does not feature in the film is the inspiration that Akutagawa drew from this remark. In 1924, after his return to Japan, once again employing his characteristic technique of writing new works based on old materials, he published a story with the title “Momotarō.”

In Akutagawa’s version, Momotarō orders his three retainers, a dog, monkey, and pheasant, to invade the paradise island of Onigashima. “Palm trees soared into the skies, and the twittering song of birds of paradise filled the air of this natural paradise. And naturally, the demons who made their lives in this paradise were peace-loving demons too.” Momotarō initiates a slaughter. He kills the adult demons himself, while his dog dispatches the young demons with a single bite. The pheasant stabs demon children to death with his sharp beak. The monkey concentrates on the women, subjecting them to humiliation and rape before throttling them to death.

The story reads like a prophetic depiction of Japan’s impending invasion of China. Akutagawa, who named his study “My Demon Cave,” seems to have discerned early on who the real devils were.

Image courtesy of NHK.

The movie ends with news of the death of Li Hanjun, who had studied in Tokyo and was another of the figures Akutagawa met during his time in Shanghai. “Momotarō” ends with the demons, conquered but unsubdued, plotting to regain their independence in the soft light of the tropical moon. “And on the desolate shores of Onigashima, five or six young demons, bathed in the beautiful light of the tropical moon, made plans for the independence of Onigashima as they placed bombs in coconuts.” Akutagawa Ryūnosuke ended his life by taking an overdose of barbiturates in July 1927. When he died, he was wearing a yukata made of fabric he had bought in Shanghai.

(Originally published in Chinese on the Japan Science and Technology Agency's Keguan Riben on December 18, 2019. Banner photo: Matsuda Ryūhei as Akutagawa Ryūnosuke. Courtesy NHK.)