“Epok’s Atelier”: Documentary Film Explores the Genius of Record Jacket Designer Sugaya Shin’ichi

Culture Art Design Cinema- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Cover Story

(© 2020 Epokku no atorie Production Committee)

There are countless documentaries that record the artistic process, but few if any delve into the creative methods behind the evocative designs of record jackets. After all, how many designers are there in the world today who specialize in this niche genre? In the past, record stores offered an assortment of music on vinyl, and there were any number of designers who were renowned for their expressive jacket covers. But physical albums have given way to music streamed over the Internet. While vinyl is gaining popularity with a small set of young aficionados, the limited demand means that only a handful of record jacket designers remain.

The recently released Japanese documentary film Epokku no atorie (Epok’s Atelier) shines a light on one of these unique figures, designer Sugaya Shin’ichi. Sugaya’s creative endeavors range from more general graphic design work, including creating covers for monthly Record Collector’s Magazine, to directing music videos and making artwork for apparel brands. But he stresses that his priority has always been designing jackets, declaring that “I got into this world because it’s what I wanted to do.”

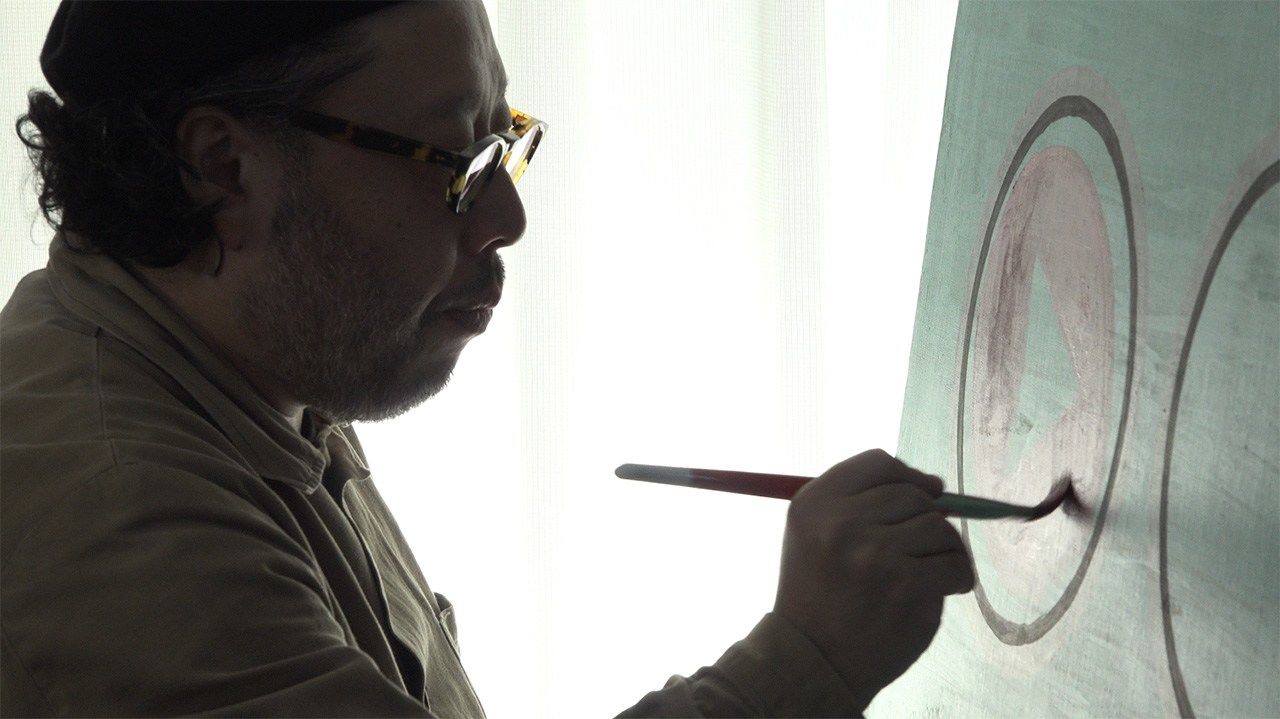

(© 2020 Epokku no atorie Production Committee)

Sugaya Shin’ichi. born in Tokyo.

Starting Out

Sugaya says that a number of coincidences led him to make designing album jackets his life’s work. Although an architecture major at university, he had a passion for photography and longed to do something related to the art. In his fourth year of college, he had lined up work as a photographer’s assistant, but the opportunity faded when he was badly injured in an accident in a car a friend of his was driving, and underwent a long hospitalization.

Barely in his twenties, Sugaya found himself confined to a hospital bed, unable to move. He says that rather than feeling anxiety about his future, the experience gave him a sense of clarity. “I didn’t fret over what I was going to do for the rest of my life,” he chuckles. “I knew it probably wouldn’t involve photography, though.” He describes feeling that he had died in the accident, but had been brought back to life. “By chance I was looked at by a famous brain surgeon, and if it hadn’t been for him I really might not have pulled through. Lying in the hospital, the thought of being a photographer vanished from my head and was replaced by a desire to do something that I really enjoyed.”

Sugaya created the mascot for the band The Cro-Magnons, an unidentified creature named Takahashi Yoshio. The documentary tells the story behind the birth of the character. (© 2020 Epokku no atorie Production Committee)

After graduating from high school, Sugaya worked for a time at a small neighborhood factory run by his father and did design on the side as a hobby. When a music and apparel select shop he frequented ran a want ad for a buyer, he applied for the job. However, in the interview he pitched himself as a graphic designer and was passed over for the position. Not long after that, though, the shop started issuing compilation CDs of their own. Remembering Sugaya, they contacted him to see if he was interested in designing their record jackets.

A Team of One

For nearly two decades, Sugaya designed record and CD jackets under the moniker “epok.” In 2008, he kept the name when he launched his own design firm.

Epok may be a company, but Sugaya is its only employee. He does everything himself, from management and production to shooting the photographs and creating the art he uses on his record jackets.

Working on the jacket for the single “Crane Game” by The Cro-Magnons. (© 2020 Epokku no atorie Production Committee)

Sugaya says that when people asked him why he does not have an assistant, a question he hears frequently, he tells them that he prefers not to have other people’s opinions getting in my way. “If there was someone else here, I would end up consulting with them, which would influence my judgement. In the end, I don’t want to have to compromise on the work I put out.”

Sugaya does get contacted by young people who want to study under him, and he admits that he has interviewed a few applicants. So far, though, he has not decided to mentor anyone.

He insists that he is not fixated on doing everything himself, but says that “I haven’t met anyone yet that made me think I wanted to work with them.” He feels a large part of his reluctance stems from his unusual start in the business. “I didn’t go to design school and I’ve never worked for a company. I’m not opposed to the idea of having an apprentice, but I wouldn’t know how to train them. I mean, I started completely from zero myself.”

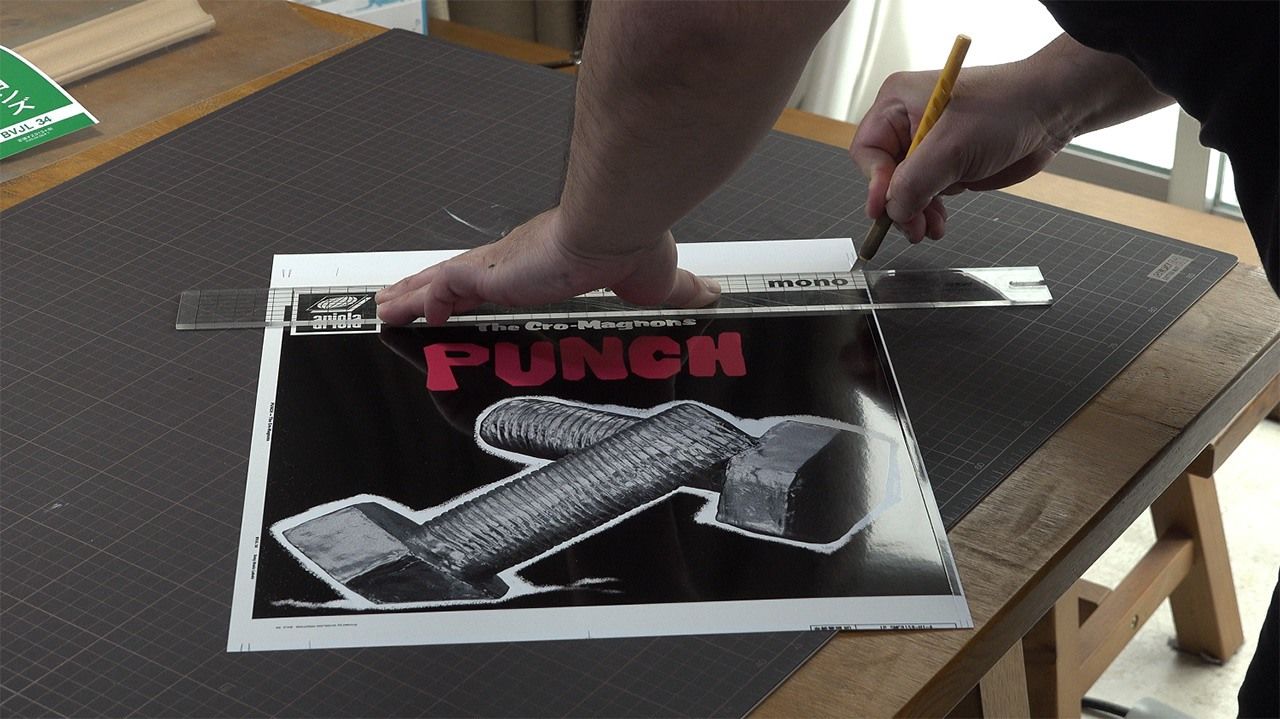

Sugaya’s production process is completely devoid of anything resembling theory. The documentary captures scenes of him creating the jacket for the single “Crane Game” by the group The Cro-Magnons, released in August 2019, and the band’s album Punch, which also came out that year.

Sugaya works on the jacket of the album Punch. (© 2020 Epokku no atorie Production Committee)

Selective Listening

Sugaya has a strict policy of listening to a record only once before setting down to design a cover. “I want to capture the full impact,” he says. “I’m trying to put into physical form what I feel. I’m after the spark, that pulse that hits me when I first hear the music.” He says he applies the same principle when out record shopping.

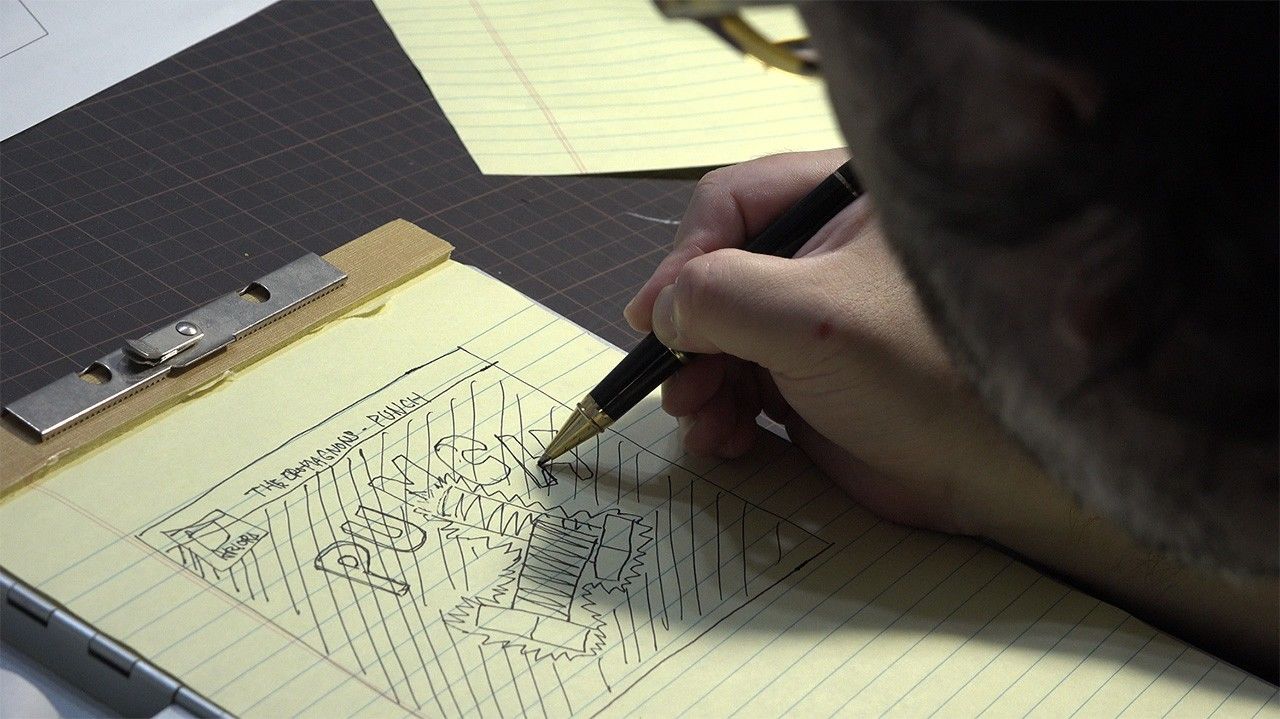

Once Sugaya has listened to the music in question, he then flops down on his belly on the sofa in his atelier and starts sketching out in his notebook his ideas as they well up in his mind.

Sugaya sketching out ideas in his notebook. (© 2020 Epokku no atorie Production Committee.)

He says he tries to visualize different aspects, such as the feel of an intro or a certain lyric, jotting down whatever comes to him. Laughing, he admits that he can get fairly drowsy during intense bouts of concentrating, but says that after a nap things usually fall into place. “When I open my eyes after an hour or so, I’ve fully fleshed out the ideas in my head.”

From there, Sugaya heads straight into production, totally absorbed. He describes himself as someone who does not work by trial and error, but who charges straight for the first goal he sets for himself. One of the few times he thought he would try a new approach and started erasing what he had done, he discovered that the eraser itself created a cool effect and he went on to use in the final version of the cover for the album Lucky & Heaven by The Cro-Magnons.

Sugaya working on the jacket for Punch. He became so obsessed with the size and texture of the giant falling bolt featured on the record jacket that he modelled one out of clay and other materials. (© 2020 Epokku no atorie Production Committee)

Sugaya is known for using nontraditional tools to create his works. “Recently, I’ve been painting with disposable wooden chopsticks,” he declares. “You might think they’re easy to control, but the cheap ones don’t convey the line of paint very well, so you get all sorts of interesting accidental effects.” Conversely, some works call for precision and Sugaya will not put down his brush until he is completely satisfied with the result. “Every piece I do calls for a different approach.”

Sugaya used cheap wooden chopsticks to create the inner artwork for the album Punch. (© 2020 Epokku no atorie Production Committee)

In short, Sugaya trusts his own sensibilities absolutely, always creating works that he finds personally interesting. There is none of the long back and forth with clients that is typical of the graphic design industry. Sugaya presents a finished work as is, confident that the customer will like what they see.

He says it took some time but that the producers and directors who use his services are used to his style. “Now when I put a work in progress in front of them, they accept it without question.”

Sugaya calls what he shows his clients “rough drafts.” But in reality, by the time he shows a customer a creation, it is already a fully realized work. In terms of concept and form, there is no room for making changes.

Sugaya shows a work to a client. (© 2020 Epokku no atorie Production Committee)

“Everything is a bit rough until it’s finished,” laughs Sugaya. “For me, it’s not the concept that counts. It’s what I see in my mind’s eye. Unlike the advertising world, I’m working with musicians, so when I show them what I’ve done, they get it, just like that. Maybe it’s a matter of being of a similar mind. We’re all music fans after all, so it’s easier for us to understand one another.”

There is no place in epok’s atelier for concepts like marketing and cost performance that are considered essential when creating new products in society today. The designer’s stance is incompatible with such catchwords as “efficiency” and “economy first.” A gentle, balmy atmosphere permeates his work space, along with peals of laughter. “I know I’ve nailed a piece when I start laughing inside.”

In addition to interviewing Sugaya and following him at work, the documentary weaves in the testimony of Kōmoto Hiroto and other members of The Cro-Magnons, members of the band Okamoto’s, graphic designers, editors, and others as it reveals the appeal of the works that emerge through the designer’s unique production process. Director Nanbu Michitobu jettisons all explanatory elements like narration and on-screen titles in favor of minimalist imagery. Yet through his meticulous editing, he delivers a message that resonates with viewers. The film is a profoundly layered work, one from which anyone who watches it can discover, from their own individual perspectives, hints for how to follow their own bliss.

A work Sugaya created spontaneously under lockdown during the first wave of COVID-19 in Japan.

Epok’s Atelier: The Record Jackets of Sugaya Shin’ichi (trailer)

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview photos by Hanai Tomoko.)