“Ushiku” Director Thomas Ash Discusses His Covert Reporting on Immigration Detainees

Cinema Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Since last year, immigration has been a hot topic in Japan. Discussion has concerned both the Immigration Bureau of Japan, which oversees immigration and residency of foreigners, and its detention facilities. The catalyst was the death in detention of former exchange student Wishma Sandamali, from Sri Lanka, in March 2021.

Her death was initially reported at a time when the Diet was deliberating a bill to revise the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act. Sandamali’s bereaved family members traveled to Japan and their efforts to uncover the truth surrounding her death were widely reported by the media.

Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan lawmaker Ishikawa Taiga questions Minister of Justice Mori Masako regarding the issue of immigration detention in a March 2020 House of Councillors Budget Committee meeting. (Courtesy Thomas Ash)

This was the prelude to revelations of problems at many levels of the immigration system, including the normalization of inhumane treatment of detainees by immigration officials. In addition, Japan’s immigration detention system was shown to violate United Nations’ human rights standards, and scrutiny exposed a lack of transparency in the screening standards used to determine whether an applicant would receive special permission for residence in Japan, provisional release from detention, and recognition as a refugee.

As a result, the government’s bill to revise immigration law, already criticized by the opposition as a change for the worse, became the subject of chaotic debate, and was finally scrapped without a vote. Plans to reintroduce the bill in the current Diet session are also presently on hold. Sandamali’s family has filed a damages suit against the Japanese government, and debate over immigration issues continues to rage.

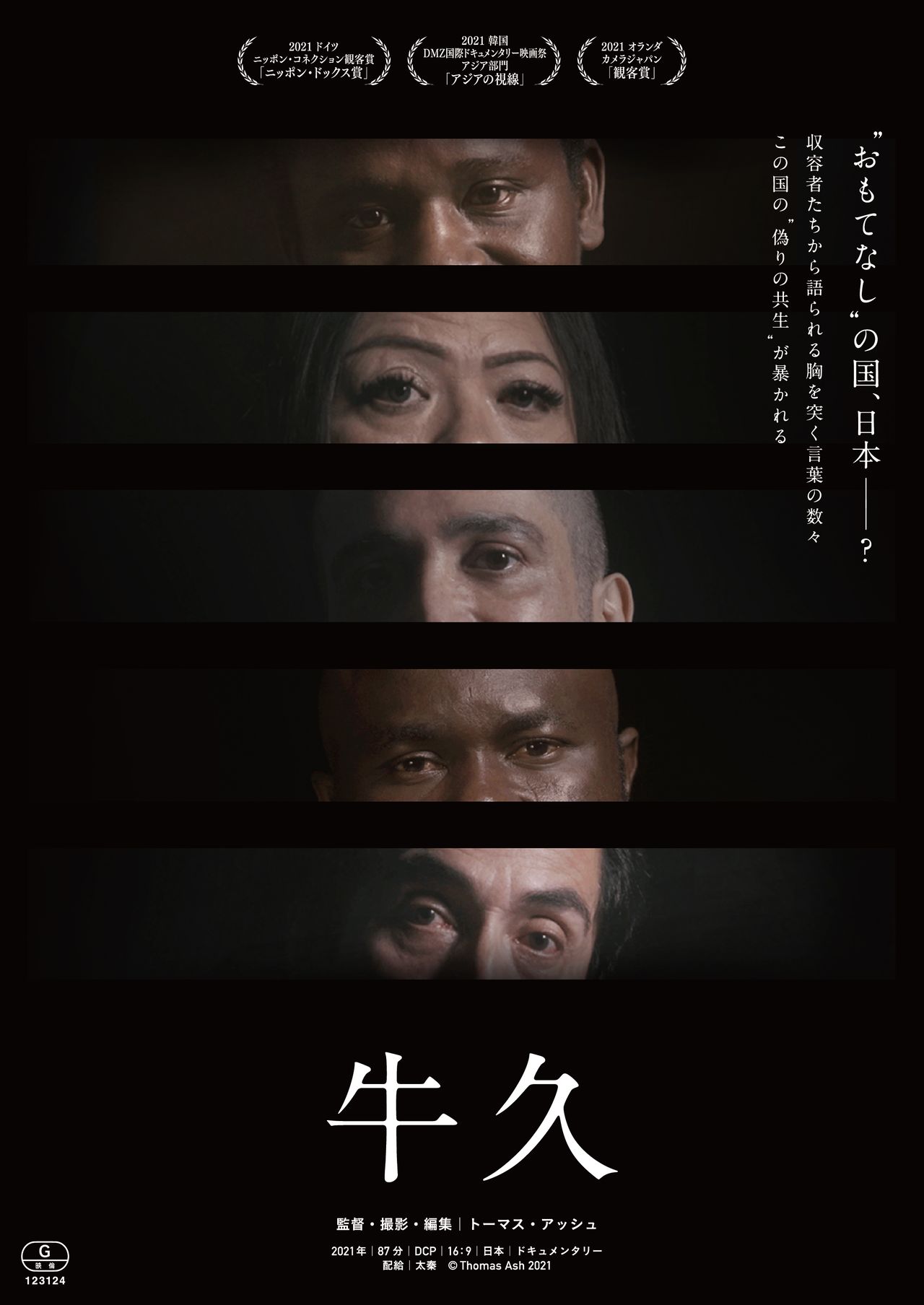

The Place They Call “Ushiku”

Against this backdrop, a new documentary film, Ushiku, shares the testimonies of immigration detainees. The film’s title is the byname for the East Japan Immigration Center, in the city of Ushiku, Ibaraki Prefecture. Currently, foreigners without residency status are detained here and at 16 other facilities across Japan, many located near main airports or in major cities.

The film’s director, Thomas Ash, began visiting detainees at Ushiku in autumn 2019, long before Sandamali’s death at an immigration facility in Nagoya. Initially, he went as a volunteer from the church he attended, and was not intending to make a film. But after he spoke with detainees, he began to fear for their safety, and resolved to record their testimonies as evidence in case anything terrible happened.

According to Ash, “There were ongoing hunger strikes at the center, and detainees were always falling ill. One had depression and attempted suicide. I was sure that, at some point, someone would die. I felt it was vital to record the testimonies of detainees as evidence, in case an incident went to court.”

Kurdish detainee Deniz. He came to Japan in 2007 and married a Japanese woman four years later. Repeated applications for refugee recognition were rejected, and he has been detained at Ushiku for many years now. (© 2021 Thomas Ash)

Detention center visitors are requested to “refrain from” bringing cameras, video cameras, voice recorders or cell phones when visiting detainees, according to the Immigration Services Agency of Japan website. But Ash decided to carry a concealed video camera to record his meetings with detainees.

“Initially, I had no intention to use this in a film. But as I learned about the conditions from detainees, I felt compelled to share the information. I discussed my plans with them, and some courageously asked me to share their stories.”

The Ethics of Secret Filming

Nine detainees agreed to appear on camera, and are seen sitting on the other side of the acrylic barrier fervently describing the inhumane treatment they suffer at Ushiku, as well as their feelings of anguish and uncertainty. The sense of urgency in the detainees’ interviews is enhanced by being filmed in the close quarters of the visitation room, but Ash says he has received some negative reactions for “breaking the rules.”

“It has been screened at film festivals in fourteen countries, but outside of Japan almost no one has challenged my covert filming. Overseas, it is considered normal: just another form of expression. My filming method only gets attention in Japan.”

Use of concealed cameras is not unusual in undercover reporting, and in this case, Ash obtained permission from the people he was filming. Controversy about bringing in the camera without official permission seems like a typically Japanese response—one Ash finds incomprehensible.

“I only filmed detainees sharing their stories. The most shocking part of the film is not even what I secretly filmed, but footage filmed by immigration officials themselves.”

The footage Ash refers to shows six or seven officers violently restraining a male detainee, Deniz, who was handcuffed and assaulted by officials in what has been labeled an act of oppression. Deniz has since launched legal proceedings against the government. The footage used in the film was submitted to the Tokyo court by the government. Essentially, it was shot by immigration officials to support their conduct.

Deniz, half-naked, being suppressed by immigration officers. (Courtesy Deniz’s legal team)

Immigration claims that the footage proves that, because the detainee was struggling, the officers used justifiable, not excessive, force. They film such incidents to justify their actions, precisely because there have been previous court cases asserting that unreasonable force was used against detainees.

If you watch the footage, it is instantly clear that it was abuse. It is fair to assume that even worse things take place that are not recorded.

“Officers couldn’t act this way if they recognized the detainees as human, just like themselves. But they forget this, creating an arbitrary hierarchy that enables them to treat detainees as lesser beings. I see this as the biggest problem. It’s not enough to just censure these six officers and consider the matter finished. They’ve simply been trained to act this way. The problem is higher up. We need to understand that the problem is structural.”

Why So Many Hunger Strikes?

Many detainees have applied for refugee status, seeking Japan’s protection, due to persecution in their home countries. Despite not being criminals, they are detained for lengthy periods, treated like prisoners, and psychologically hounded. In a way, it is more unbearable than ordinary imprisonment, because their future is so uncertain.

Desperation causes many to see hunger strikes as their only hope. They believe that if they starve long enough, their situation may be assessed as “risky,” securing them a provisional release. But even then, they must report back after two weeks, when they are generally re-interned. The absurdity of this is obvious in the testimonies of detainees seen in the film.

“Why does this happen? I’d like to ask immigration myself,” says Ash. “Basically, if someone happens to die in detention, it would cause problems. I believe they release the detainees so they will eat and regain the strength for redetention.”

In March 2020, Deniz was reunited with his wife when he was temporarily released from Ushiku. (© 2021 Thomas Ash)

This was only the case during filming, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the infection spread in Japan, from March 2020, there has been an increase in provisional releases across Japan in order to minimize close contact. Ironically, the pandemic has had a beneficial effect in that detainees have not had to resort to hunger strikes. But once Japan overcomes the virus, it seems likely that the situation will revert back. One point to remember, though, is that even gaining provisional release does secure a far more humane lifestyle.

As Ash explains, though, it is not a normal lifestyle providing much comfort. “They don’t have the right to work, or health insurance, and don’t receive public welfare. They must rely on help from allies. Even though they are physically able to work, they aren’t allowed to. It’s humiliating to be forced to rely on the favor of others simply to eat.”

Acting as a Witness

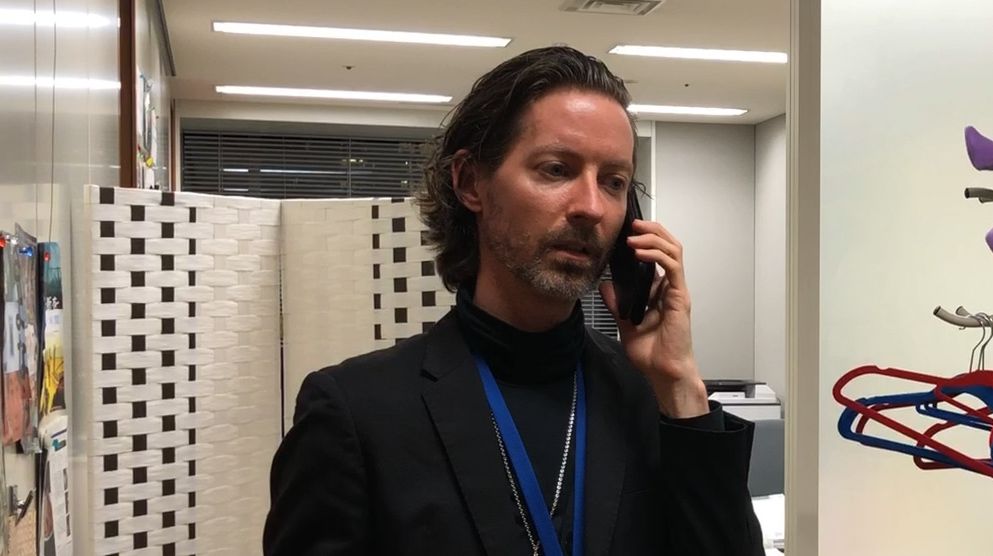

Aside from the two years when Ash studied in Britain, he has lived in Japan continuously since 2000. In 2011, he reported on the situation of children who were found to have thyroid gland growths after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. Ash says that, because he loves Japan, he does not want to turn a blind eye to its issues. His gentle demeanor is not what you would expect of the director of such films, but he seems to be concealing anger within.

“I don’t think I’d describe what drives me as anger, necessarily. But I tend to be drawn to people shunned by society. Then I become curious about the problem. I question why fellow humans are treated this way. If I am angry, it’s not toward Japan or the party perpetrating exclusion: I’m angry about the issue itself. Also, I’m angry at myself for being unable to do anything.”

Ash challenges us to be conscious of our responsibility to be witnesses to wrongdoings we see in society.

“I understand it’s only human to want to avoid involvement. But if you turn a blind eye, one day it will come back to haunt you. If we fail to address one issue, problems multiply, and society deteriorates. That’s why, when we see unfairness, we have to speak out as witnesses. Nine detainees themselves were brave enough to raise their voices. I have great respect for them. Also, I feel a heavy responsibility, because they entrusted their testimonies to me.”

In response to people criticizing his use of concealed cameras in filming Ushiku, he notes: “These are mainly people who haven’t seen the film. Some might be initially alarmed by the words ‘secretly recorded,’ but I believe they’ll understand why I had to do it when they see the film.”

Ash is grateful to the many people who helped him to complete the film and finally achieve its release. But because the issues are still unresolved, he is adamant that his work is not over.

“My hope is that people who see the film will want to know more about the issues and will investigate it further. I’ve gotten involved by making the film, but everyone has a different role to play. I hope it will lead to a range of actions. Even just talking to someone else is something. If more people learn about the issues, it could lead to a solution. What I fear the most is indifference.”

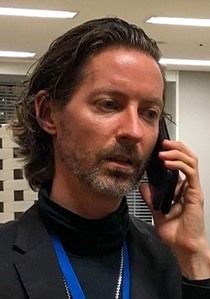

Ushiku director Thomas Ash. (© 2021 Thomas Ash)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: a scene from the film Ushiku, depicting the East Japan Immigration Center visitation room. © 2021 Thomas Ash.)

Ushiku (2021)

- Written, directed, and edited by Thomas Ash

- Country: Japan

- Distributed by Uzumasa

- Running Time: 87 minutes

- Official site: https://www.ushikufilm.com/en/

immigration cinema Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act TITP