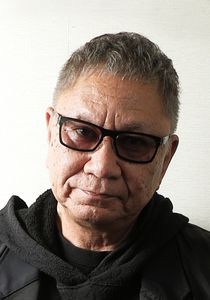

Director Miike Takashi’s “Sham” Explores the Line Between Truth and Lies

Cinema- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A teacher walks through the pouring rain late at night to visit a student’s guardian. The beautiful mother welcomes him politely and serves coffee. The teacher is there to discuss his student, the woman’s son, who is causing problems in class.

During their conversation, the mother reveals that the boy has roots outside of Japan, and the teacher comes to believe that what he has seen as problem behavior stems from his not being “pure Japanese.” From then on, the teacher begins saying discriminatory things, becomes aggressive, and eventually escalates to physical violence. The mother’s anxiety grows as tensions with the teacher build.

Elementary school teacher Yabushita, played by Ayano Gō, is accused of abusing Takuto, played by Miura Kira. (© 2007 Fukuda Masumi/Shinchōsha © 2025 Sham Production Committee)

Thus opens Sham, a new film from director Miike Takashi. The question becomes, how much of this is true? And does truth ultimately depend on who is telling the story? Miike is quick to sow such doubt in the audience’s mind.

Miike is one of the most globally famous directors working in Japan today and is widely known for scenes of extreme violence and audacious works that defy genre convention. Many consider Audition, Ichi the Killer, and 13 Assassins to be his most identifiable works, but he has had a hand in over 100 films altogether. The variety is huge, from comedies and musicals to horror and action. It might be difficult to find a genre he hasn’t tried.

Ritsuko, played by Shibasaki Kō, insists her son is facing at the hands of his teacher. (© 2007 Fukuda Masumi/Shinchōsha © 2025 Sham Production Committee)

The Gap Between Media and Reality

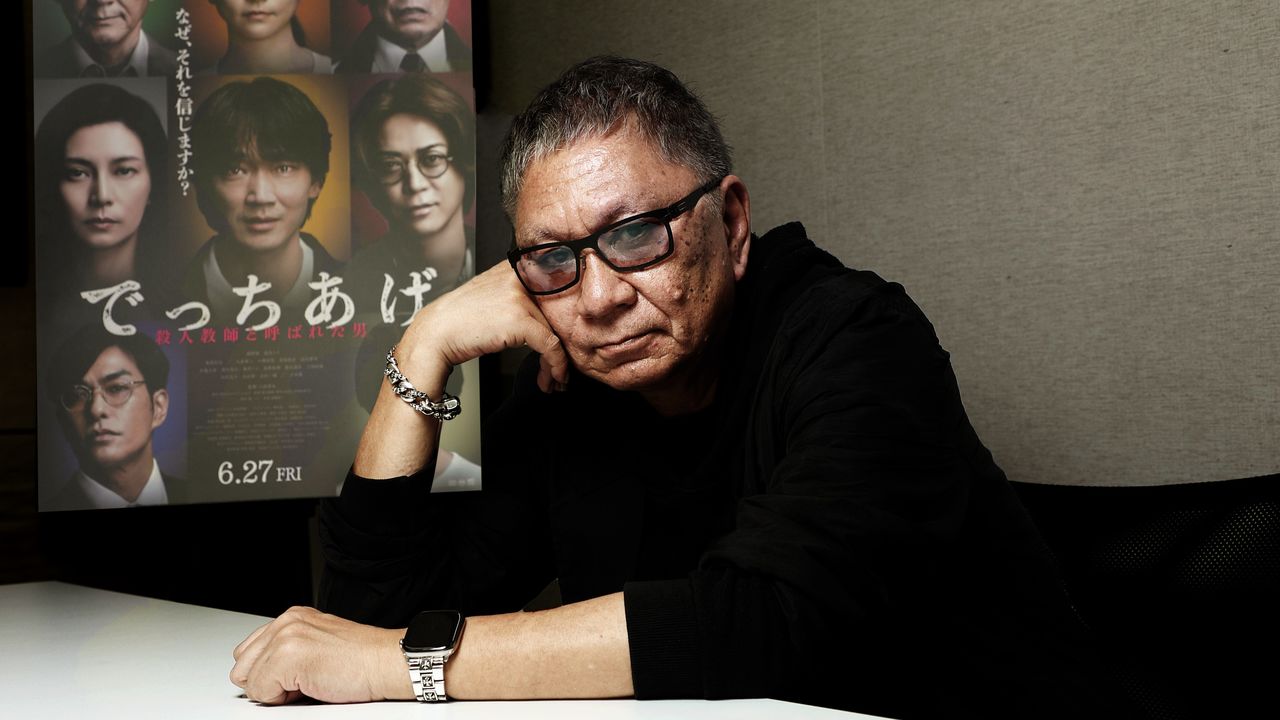

Miike’s target this time is an unusual one for him, a social drama. The work weaves together various topics always on the minds of the Japanese public: the halls of education, bullying and PTSD, overbearing parents, and the role of the news media. The background of this is a real case that happened in Fukuoka in 2003, but Miike himself is reluctant to say it is “based on a true story.” He is careful to draw a hard line between “truth” and “film” and not seek to cross it.

“I read the book about this case [Fukuda Masumi’s 2007 Detchiage: Fukuoka satsujin kyōshi jiken no shinsō (Fabrication: Digging Deep into Fukuoka’s Killer Teacher)]. It was fascinating. I was only able to make the film because of that reportage. When you try to make a movie based on a true story, it takes years. You need to do interviews with the real-life people the characters are modeled on to put their story together, and to make sure all of them are on board with what you’re doing in your film, if they’re still alive. And if we tried to do all that ourselves, we just wouldn’t have had the time.”

It is no surprise to hear Miike talk about the limits of time when discussing movie making. From his big-screen debut in 1995, he has produced work at an astonishing pace. It is not unusual for him to work on three or four projects in a single year. Of course, he always focuses on maintaining his professional quality. There surely can’t be many directors in the world who can follow suit.

Sham revolves around a story told by Takuto’s parents about how his elementary school teacher Yabushita begins verbally, and then physically, abusing their son in class. They insist that their son has shown physical injury and symptoms of PTSD.

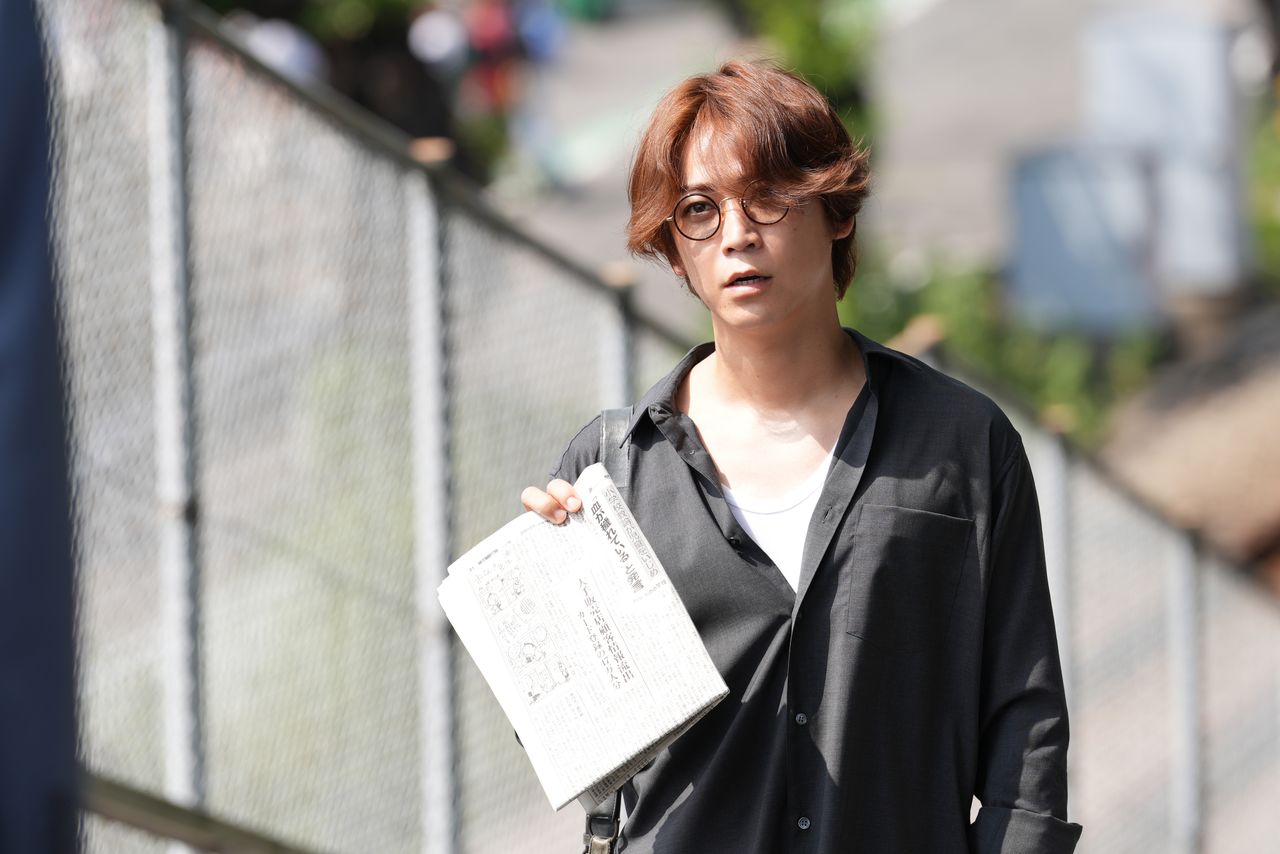

Takuto’s mother, Ritsuko, contacts tabloid reporter Narumi, played by Kamenashi Kazuya. The reporter immediately smells a story and begins hounding Yabushita. Narumi’s reporting ends up shaping public opinion in deciding exactly what happened and who was at fault.

Tabloid journalist Narumi reveals Yabushita’s name and openly accuses him of physical abuse of a student. (© 2007 Fukuda Masumi/Shinchōsha © 2025 Sham Production Committee)

“Perhaps the media isn’t the only problem,” says Miike. “It’s the consumer side that takes in the information and creates that kind of atmosphere. The media’s job is to report information. And tabloids try to sell magazines by taking a sensationalist approach. From the media and business perspective, that’s somewhat unavoidable, in a sense. These days in particular, we’re all flooded with information through social media and everything, so our interest jumps from thing to thing, and we can end up harming people without even being aware of it. So, I don’t think the problem is solely on the media’s side. That’s something I found interesting in reading the source material for this one.”

Master Actors

Miike chose a quiet tone to tell such a weighty story, resulting in a work that stands in stark opposition to the blood drenched, breathtaking tempo of his most famous works. At the same time, this work is not without fearfulness. It brings a hefty dose of the terrifying nature of humans, based firmly in reality.

The boy and his parents sue the city of Fukuoka and the teacher, ending up with the backing of a legal team some 500 strong. (© 2007 Fukuda Masumi/Shinchōsha © 2025 Sham Production Committee)

The work avoids any sensationalized production, and there is no hint of humor to offer an escape for the audience. Viewers have no choice but to face head-on the merciless brutality of humanity. On top of that, the pitch-perfect performances from the cast keep the eye nailed to the screen for the film’s two-hour-plus running time.

Miike says: “I try to create scenes dispassionately, without pushing any specific idea. I don’t use music to create mood, either. It’s the same with the acting. It’s like, that kind of pressure would probably make someone cry in that way. I want to give the actors space to perform, but I try to keep them reserved, performing without excessive passion, what you’d call enthusiastic performance.”

The two lead actors offer up performances that are like a dance between two masters, maintaining a perfect distance. Shibasaki Kō, playing the mother of the allegedly abused boy, can change the feeling of a scene by a simple change of expression. Even amidst such a restrained performance, the wealth of expression she brings is impressive. And her opposite, the teacher played by Ayano Gō, only raises the level. The intense humanity of his actions and the depth of his emotions offer a powerful contrast to Shibasaki’s reserved acting.

This is Shibasaki Kō’s third time working with Miike. (© 2007 Fukuda Masumi/Shinchōsha © 2025 Sham Production Committee)

Miike explains his hands-off approach to handling his performers. “As actors, everything they do gets scrutiny from the media. Surely they feel more isolated from the world than anyone. And even so, they are strong enough to stand on their own two feet and perform in front of the public. I think there was probably a part of them that understood the roles because of that. If you overexplain things to actors with words, there’s a danger of their overacting, but with these two it just came naturally.”

The whole cast, particularly Kamenashi Kazuya as the reporter and Kobayashi Kaoru as a lawyer, offer outstanding performances that serve as the icing on an already excellent cake.

Lawyer Yugamidani, played by Kobayashi Kaoru, takes over Yabushita’s case. (© 2007 Fukuda Masumi/Shinchōsha © 2025 Sham Production Committee)

The Global Reach of Local Focus

Despite the quality of the finished work, though, it might well be that Miike fans overseas will struggle to understand this film due to the Japanese values and norms working in the background. The act of apologizing just as a way of making a problem disappear—something that takes the case in an irreversible direction in the film—could be called a truly Japanese approach to problem solving. That development could well be stressful to watch for audiences outside Japan.

“When you’re trying to share information widely, the tendency is usually to aim for global accessibility. But with films, even the most extreme stories seem to somehow come across. Even some story about a shoplifting family found a proper audience overseas,” laughs Miike, referring to Koreeda Hirokazu’s 2018 Shoplifters. “Under normal circumstances, you know, they’d have no idea how these people live or what they’re thinking about. But even without understanding that, there’s a sense of reality that somehow resonates with people. In the truest sense, aren’t the pieces that truly work globally the ones that narrow in on a target, and end up local? I think people outside Japan who watch this film will likely end up confused. But that’s fate. I won’t change the piece for that.”

Yabushita is compelled to apologize in front of parents at a public meeting. (© 2007 Fukuda Masumi/Shinchōsha © 2025 Sham Production Committee)

The director’s mention of Shoplifters, calls to mind another Koreeda work. It is impossible to watch Sham and not be reminded of the 2023 Monster. Both films deal with abuse in schools, and both explore shifts in what “truth” is based on who tells the story.

However, pointing out such connections is somewhat simplistic. Personally, I feel a better comparison is found in Miike’s own 2011 work Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai. Based on the same source material as director Kobayashi Masaki’s 1962 film Harakiri, it was highlighted by a gorgeous score by Sakamoto Ryūichi and premiered as the first-ever 3D work at the Cannes Film Festival.

Yabushita’s only salvation is the support of his wife, Nozomi, played by Kimura Fumino. (© 2007 Fukuda Masumi/Shinchōsha © 2025 Sham Production Committee)

Sham resembles that period drama both in structure, tone, and the anxiety it creates in its audience. Hara-Kiri and Sham are also similar in their restrained violence and lack of any ghosts or other supernatural elements. However, that same fearful space is occupied by the extreme brutality of human existence. Isn’t that what scares us all the most?

True film fans should set aside any preconceptions formed after watching Miike’s past outings. It may not offer shocks like the 2001 Ichi the Killer, which famously had sick bags for the audience when screened at the Toronto International Film Festival that year. But this film is a uniquely “Miike-esque” experience like none before.

Trailer (Japanese)

(Originally published in Spanish. Banner photo: The film director Miike Takashi. © Hanai Tomoko.)