The Dark Side of the Japanese Internet

Murder Online

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

“You Seem Troubled. Do You Want to End It All?”

It was on October 30, 2017, that the dismembered bodies of nine people were found in a rented apartment in Zama, Kanagawa Prefecture. Shiraishi Takahiro, charged initially with robbery and forcible intercourse, had used Twitter and other social media channels to approach young women who said they wanted to die, taking advantage of their unsettled mental state to lure them to his apartment and to their deaths.

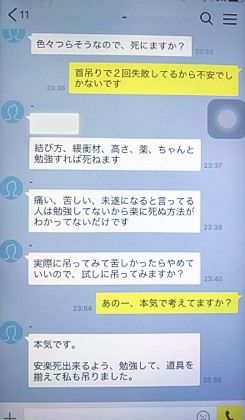

Line messages exchanged between Shiraishi and the high school girl.

The deceased were not the only ones that Shiraishi had been involved with online. One female high school student who luckily escaped death had exchanged a series of messages with Shiraishi on the free messaging app Line.

Shiraishi: You seem troubled. Do you want to end it all?

Girl: I tried to hang myself twice, but it didn’t work and now I’m at my wits’ end.

Shiraishi: You can do it if you read up on how to tie the rope, padding, height, drugs, and so forth. People fail to kill themselves or end up suffering because they don’t study up on how to do it properly. Do you want to try it with my help? I promise we can stop if you find it too painful.

Shiraishi, interviewed by the media while in police detention in Tachikawa, was asked why he had committed his crimes. He answered frankly, making no attempt to hide his totally self-centered nature: “I wanted money and I wanted to fulfill my sexual desires.” “I killed the victims to hide the evidence,” he also admitted, noting, “I don’t feel any remorse.”

From the “Dr. Kiriko Incident” to Hook-Up Site Murders

There have been numerous murders where the Internet was involved. One of the oldest cases, dating back to December 1998, is the “Dr. Kiriko incident,” in which a young woman ingested a cyanide capsule sent to her. This was treated as a case of abetting suicide.

Here are the details: a website promoting euthanasia included a bulletin board called “Dr. Kiriko’s Medical Advice.” People wishing to commit suicide could consult with the “doctor,” who took his name from a character in Tezuka Osamu’s medical manga series Black Jack. He sent several individuals, including the woman who died, cyanide capsules “on loan.” Called “emergency capsules,” under the agreement between Kiriko and the recipients, the cyanide pills were to be returned in five years’ time. The reasoning behind the arrangement was that if people knew they could do away with themselves anytime, they would ultimately change their minds. Kiriko’s position was that he was stopping them from committing suicide, rather than abetting the act.

But the woman in question went ahead and took the cyanide, and shortly thereafter the man behind the Kiriko persona killed himself the same way. The police served papers on the dead man and the case was closed.

In 1995, the Internet was in its infancy in Japan. Microsoft’s Windows 95 had just been released, and Internet usage had begun spreading among the general public. In 1998, the year of the Dr. Kiriko case, the penetration rate for the Internet among ordinary users was 13.4%, the first time the rate had exceeded 10%, according to official government statistics. Police statistics reveal that 1998 also saw 32,863 suicides, the first year the suicide rate exceeded 30,000.

In the Dr. Kiriko incident, the Internet had been used as a tool for facilitating suicide. But a change occurred in the type of Internet-mediated crime with the emergence of murders via hook-up sites.

In January 2001, an 32-year old housewife from Saitama Prefecture, sustained severe injuries after she was stabbed by an 18-year old male high school student from Tochigi Prefecture. This case of attempted murder was not a random attack; the two had met through an anonymous hook-up site for heterosexual couples. The woman, exhausted from caring for her bedridden mother, sought to relieve stress by engaging with male users of the site.

In the course of their online relationship, the woman asked the student to kill her. The student urged her to reconsider, but she was adamant that she wanted to end her life. Five days before university entrance exams, the student absented himself from school, claiming he had a cold, and headed for the woman’s home. He made a last attempt to dissuade her from her plan but ended up empathizing with her instead and stabbing her.

In April 2001, a female university student aged 19 was murdered in Kyoto after telling a friend that she was going to meet someone with whom she had been exchanging email messages. A 25-year old construction worker arrested for her murder said the two had met online and that he had killed her after a quarrel about money. The man had also killed another woman, aged 28, stealing her handbag and pawning it.

A Chain of Internet Suicides

In light of these incidents, the government enacted legislation regulating these websites, prohibiting access to them by persons younger than 18. Local youth protection ordinances were also passed to encourage filtering of online sites. But online communications had gone in a new direction—murder—by then.

In September 2003, a 19-year old youth from Saitama Prefecture was arrested for the stabbing of a 46-year-old male company president from Tokyo. The two had met through an online bulletin board, where the company president was looking for someone to kill him. His company saddled with debts, the man wanted to die to obtain insurance money and pay off the bills. Although the man did not die, the youth was arrested for attempted delegated murder, having received a “starter fee” of several hundred thousand yen from the man, with a promise of a further ¥1 million reward if he succeeded in the killing.

Suicides in 2003 numbered 34,427, the highest figure ever. From 2001 to 2003, the unemployment rate exceeded 5%, and the economy was faltering. Around this time there was also a spate of suicides among people who had met online, who often killed themselves in small groups by burning coal briquettes in a car or other confined space, where they succumbed to carbon monoxide poisoning.

Doorway to Darker Crimes

Cyberspace later became the vehicle for increasingly serious crimes, which can be viewed as a precursor to the Zama killings. There was now a proliferation of “suicide by murder” sites pretending to show concern for troubled individuals, who would be lured to their deaths by thrill killers.

In February 2005, the body of a 25-year old woman was found near a soil erosion control barrier in the city of Kawachinagano, Osaka Prefecture. A male contract worker, arrested for her murder six months later and subsequently executed, had befriended the woman online and met with her, saying they would commit suicide together.

The killing had been particularly gruesome. After meeting the woman, the man bound her hands and feet with zip ties, covered her mouth with tape, and pinched her nose until she lost consciousness. He then slapped her cheeks to revive her, repeating the process for 30 minutes until he finally choked her to death. His motive: experiencing thrills by watching her repeatedly faint in agony. By the time the woman’s body was found, the man had killed two other people, a junior high school boy and a male university student, using the same method.

August 12, 2005: Osaka Prefectural Police search a pond for a victim’s belongings disposed of by the serial killer. (© Jiji)

It was also around this time that news reports of “dark” online sites specifically for criminal activity began to appear. With names like “Alternative Job Center” and the like, these sites were used to exchange information about antisocial behavior such as buying and selling drugs, recruiting people to commit crimes, and so forth.

One of the most sensational cases involving a dark site was the murder of a 31-year-old female office worker in Nagoya in August 2007. Three men who met on a dark site got together to commit robberies but bungled the jobs. Frustrated at their lack of results, they hatched a plan to abduct a woman and force her to hand over her savings.

“So, who do we abduct?” went their conversation. “If we’re going to do it, let’s get a young woman. That’ll get us all hyped up.” Without any more justification, they dragged the victim, who just happened to be walking by, into a car and killed her with hammer blows to the head. Subsequently arrested and tried, of the three perpetrators one was executed and the remaining two were sentenced to indefinite detention equivalent to life sentences.

Slang, Vague Language to Attract Perpetrators

As online crime became more vicious, police authorities stepped up cyber patrols, focusing on explicit postings either announcing murders in advance or soliciting killers. At the Internet Hotline Center set up in 2006, operators contracted by the National Police Agency are tasked with detecting unlawful or pernicious postings related to suicide or criminal behavior, and can alert police and request that Internet providers delete the postings. The Act on Development of an Environment that Provides Safe and Secure Internet Use for Young People, enacted in 2008, made using a website filtering service mandatory for mobile phones.

Providers subsequently shut down numerous dark sites and the number of postings openly encouraging criminality has dropped. But even so, there are still dark sites using slang or ambiguous wording that continue to attract people up to no good.

Just recently, in June 2018, a crime reminiscent of the worst of the dark site incidents occurred in Hamamatsu, when a 29 year-old nurse on her way to her car after a gym workout was snatched in the parking lot and killed. This time, the three killers, men previously unknown to each other, had been brought together through a popular local online bulletin board, not a dark site.

The posting that was the catalyst for the crime read “Seeking two or three people to work as a team. We operate all over the country, so if you’re unattached, any age or sex welcome. Meet-up possible on the day itself. Anyway, drop us an email.” It was titled “Hey, want to make a pile of money?” and was posted by the likely instigator, a 39-year-old man, two days before the crime. Two men took the bait, met in Hamamatsu, and carried out the kidnapping and murder. After the crime came to light, the instigator was found dead in a hotel room in Niigata City, a likely suicide.

On the positive side, the spread of the Internet has enabled users to make personal and business connections in ways that were not possible before. But the Internet has also revealed the seamy underside of society. The perpetrators of the crimes described here did not share traits in common that led them to crime via the Internet. Rather, their behavior reflects the problems—insecure employment, lack of jobs, despair over the future—that afflict Japanese society today.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 6, 2018. Reporting and text by Shibui Tetsuya; editing by Power News. Banner photo: A police vehicle carrying suspect Shiraishi Takahiro leaves the Tokyo Metropolitan Police’s Takao police station on November 1, 2017. © Jiji.)