Governments Face a Time of Trial as COVID-19 Crisis Mounts

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Xi Jinping’s “No Handshakes” Hospital Inspection

On February 10, Chinese President Xi Jinping paid a visit to the Ditan Hospital in Beijing. Wearing a blue face mask, he declared that his government would do everything necessary to ensure that the country overcame the novel coronavirus. He spoke by video link to medical workers at a hospital in Wuhan, the city in Hubei Province at the center of the outbreak, encouraging staff in their efforts and promising the support of the government. He also spoke to ordinary people on the street outside the hospital, but citing the “unusual circumstances,” he refrained from shaking hands throughout his inspection.

Wuhan has been in lockdown since January 23 following the government quarantining the city ahead of the busy Chinese New Year. Although some experts have praised China for moving rapidly to contain the virus, recent information suggests that Xi was calling for a response to COVID-19 as early as January 7. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited Wuhan to see conditions for himself on January 27, but so far, Xi has not journeyed to the frontline of the crisis.

Failed Lessons of SARS

The Beijing Ditan Hospital specializes in infectious diseases—it is a leader in the treatment of AIDS—and was one of the facilities that treated patients during the SARS epidemic.

I was part of a group of foreign correspondents in Beijing who toured an isolation ward in the hospital on April 17, 2003, during the height of the outbreak. In preparation for the visit, I bought a white hazmat suit for 400 yuan (around ¥6,000 in those days), as well as a face mask, gloves, and shoe coverings. I still remember a sign reading “Ward Number Two” as I entered the isolation area with my camera.

Normally an isolation ward would be accessed by automated double doors to prevent contamination, but here there was only a single, regular door, which had to be physically opened. I was also surprised to discover that far from being sealed and kept at negative room pressure to prevent any pathogens from escaping, the ward was wide open to the outside, with windows in rooms left open.

The author visits the quarantine ward at Beijing’s Ditan Hospital on April 17, 2003. The writing on the suit reads “For use in Chinese regions only.” (© Izumi Nobumichi)

SARS patients in the isolation ward at Ditan Hospital. Note the open windows. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

On April 20 that year, the Chinese Ministry of Health announced that cases in Beijing had increased to 339, a nine-fold jump, and that fatalities had shot up from 4 to 18. The news triggered a frenzy of stockpiling. Food items and other daily necessities vanished from supermarket shelves as panic gripped the city.

The government’s poor initial response made the SARS epidemic worse, and the initial delay in releasing information was at least partly to blame for the sudden surge in infections. Ironically, authorities kept a tight seal on critical information even as the virus was free to escape through the open windows of the supposedly isolated quarantine ward. Have the lessons been learned? It seems not. Once again, many people have criticized the Chinese government for its sluggish initial response to this latest crisis and for attempting to cover up the facts again.

Censorship, Fear, and a Lack of Trustworthy Information

During the SARS crisis, authorities sealed off buildings and districts where infections had been found. Theaters and cinemas closed, and normally crowded areas like Beijing’s Wangfujing shopping street became almost deserted as people stayed away. Some of the images we are seeing from China today could almost have been taken 17 years ago.

Normally one of the busiest areas of Beijing, Wangfujing was almost deserted on April 26, 2003. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

An almost deserted Tiananmen Square on May 1 (May Day), 2003. As the SARS epidemic worsened, more than 10,000 people were placed under quarantine. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

Empty tables dominate this popular restaurant in the Dongcheng district of the capital on May 13, 2003. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

The atmosphere prevailing in Chinese society today is quite different. With censorship and other restrictions on speech stricter than ever, it is not easy for experts to speak their minds. Bureaucrats, too, tend to say nothing, in silent deference to the presumed wishes of the government. Certainly, this climate of silence and fear was one of the reasons for the delay in making information available and the sluggishness of the government’s initial response.

On top of this, Li Wenliang, the doctor who first warned at the end of last year of the risk posed by a new type of viral pneumonia, was rewarded for his honesty and public spiritedness by an official reprimand and a warning to stop making “false comments.” Li ultimately died from the infection himself on February 7 at the age of just 33.

News of this tragedy spread quickly over the Internet, prompting widespread anger at the government’s response. Even while praising Li as a hero, authorities continue to censor online discourse and remove posts critical of the government.

The Need for International Solidarity

On January 30, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global health emergency. A month since then, more than 90,000 cases have been confirmed worldwide and more than 3,000 people have died. Although China remains the center, the outbreak is picking up speed in other countries. Japan has had more than 280 infections so far, and six fatalities.

On February 15, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of the WHO, admitted at the Munich Security Conference that it was impossible to predict the future development of the epidemic. He said there was no room for complacency and no way of knowing when infections would peak.

At the same conference, Japan’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Motegi Toshimitsu met with Chinese counterpart Wang Yi and declared Japan’s readiness to cooperate and assist the Chinese government in its response to the new virus. The two ministers agreed that Japan and China would work together to combat the threat.

It is vital for the world to pool its resources to combat this invisible new enemy. This is a test for our systems of global governance and will reveal how well we can cooperate across borders and show solidarity across different systems. Unfortunately, there have been ugly incidents of racial discrimination and prejudice targeting people of Asian appearance, including Chinese and Japanese, in many Western countries, bringing to mind the racist “Yellow Peril” ideology of the nineteenth-century. Now more than ever, it is vital that we reject such bigoted ideas and that the entire international community work together to bring the epidemic under control.

Controlling the Situation in Time for the Olympics

The COVID-19 epidemic has already caused a slew of events to be canceled or postponed. In China, the National People’s Congress, originally scheduled to start on March 5 in Beijing, has been postponed and Xi Jinping’s state visit to Japan, scheduled for April, is also likely to be knocked back.

In Japan, a growing number of concerts, sporting events, and conferences have been scrapped. Not even Japan’s royal family has been spared. On February 17, the Imperial Household Agency announced that the traditional visit by the general public to the palace in celebration of the emperor’s birthday would be canceled to prevent the spread of the virus; the event would have been the first such occasion since the Emperor Naruhito took the throne last year. However, the biggest events on the calendar for this year are the Olympic and Paralympic Games, due to be held in Tokyo from July to September.

Unlike the situation facing Japan, the SARS crisis ended five years before Beijing hosted the Olympics in August 2008. Chinese authorities worked closely with the National Bureau of Statistics, and on June 24, 2003, announced that the outbreak had been contained and the situation brought under control. The declaration was carefully planned under the close supervision of the central leadership of the Communist Party.

During the SARS outbreak there were no confirmed cases in Japan. But this time Japanese communities are on the frontlines of the fight. The government has already come under criticism for its slow and confused response to the risk of mass infection on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship that was placed under quarantine in the port in Yokohama.

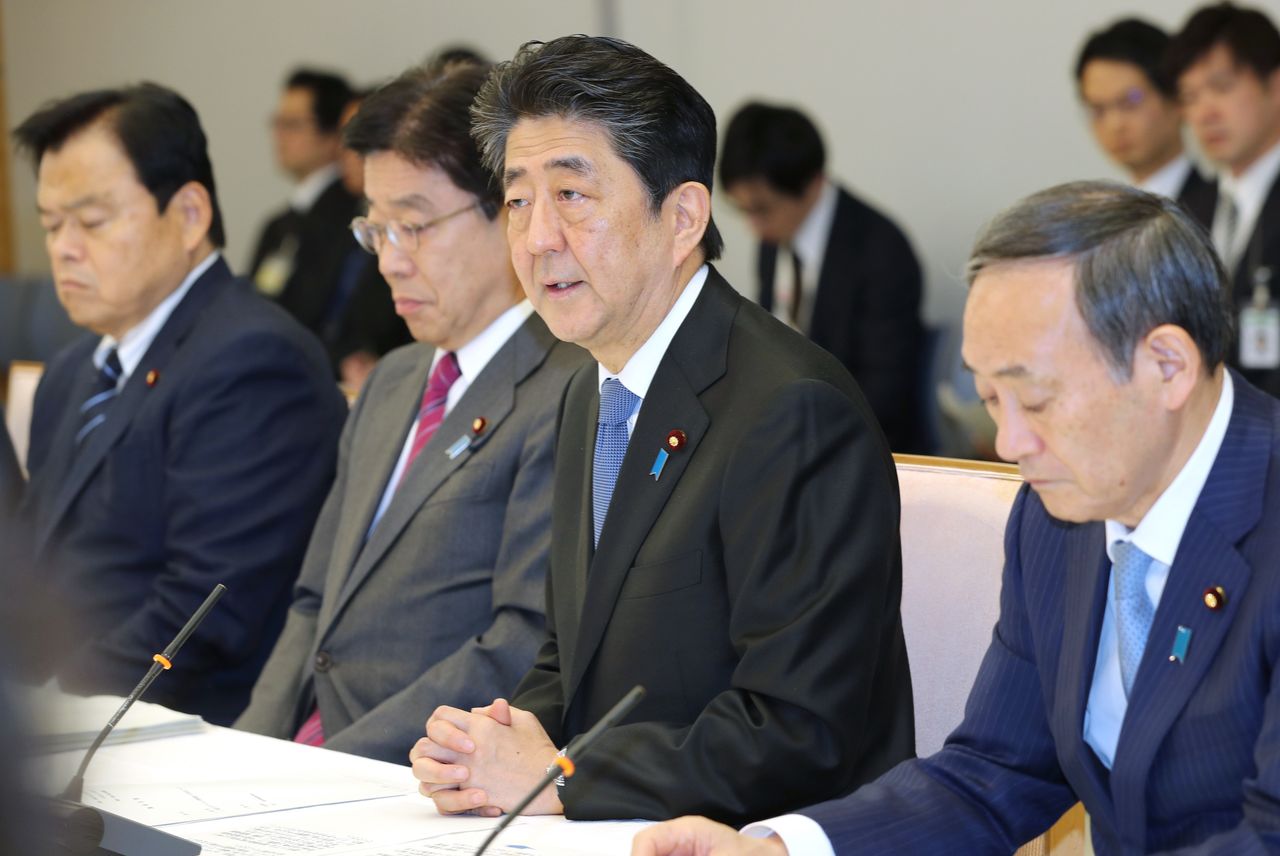

On February 16, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō chaired the tenth meeting of the government’s taskforce to address the crisis, where he appealed for people to do whatever they could in their daily lives to prevent the epidemic from spreading further. He has since rolled out preventative measure, including requesting the nation’s schools to close for several weeks, with more expected.

How should the government put together and implement a scenario for containing the outbreak and mobilize the experience and expertise at its disposal? The coming weeks and months are likely to prove a stern test for the crisis management skills of the prime minister and those around him.

Prime Minister Abe Shinzō speaks at a meeting of the government taskforce to address the COVID-19 crisis on February 16, 2020. (© Jiji)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: On a visit to the Ditan Hospital in Beijing, Chinese president Xi Jinping encourages medical workers in Wuhan via video link. © Xinhua/Aflo.)