Scapegoats Not the Solution: An Interview with Otsuji Kanako

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Debate Removed from Reality

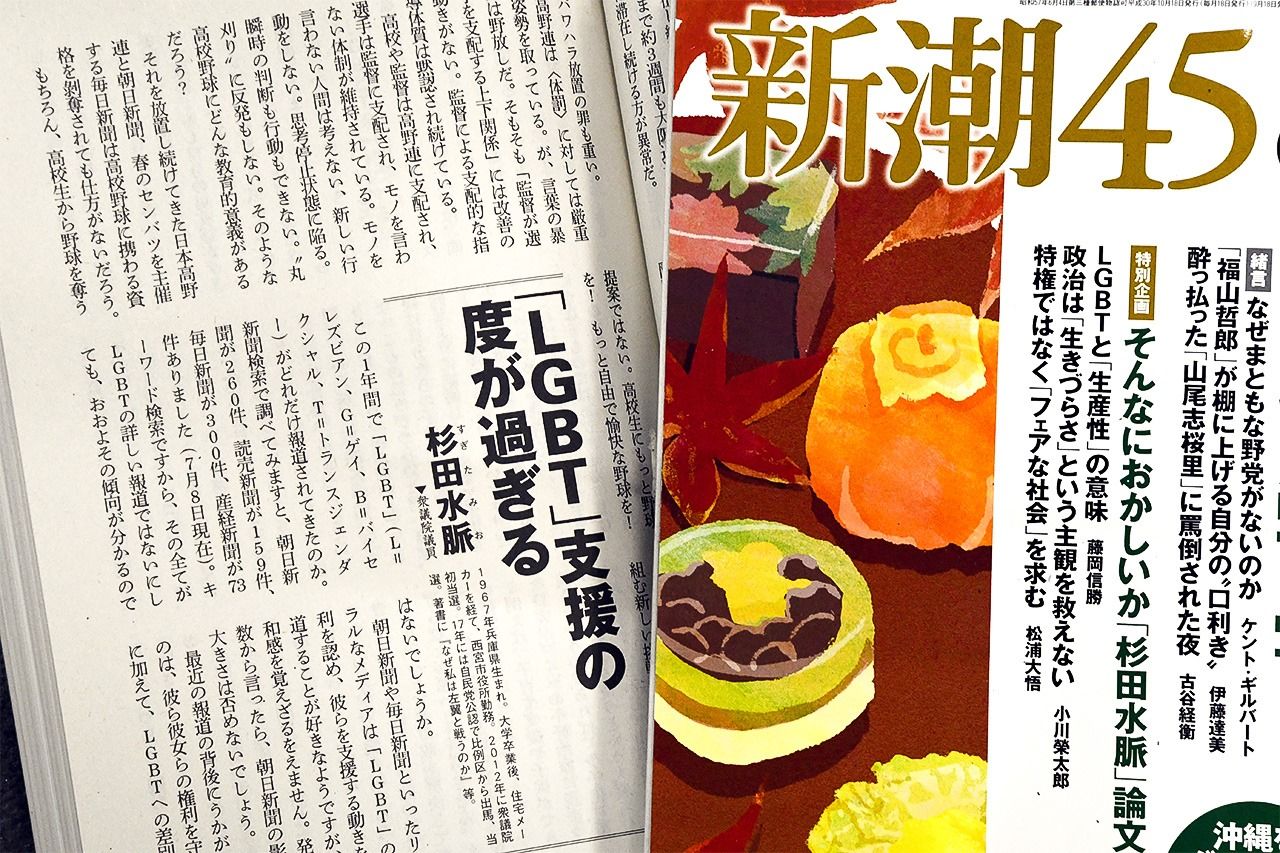

A magazine article by Liberal Democratic Party lawmaker Sugita Mio created waves with its claims that the LGBT community receive too much support. When it hit newsstands in July 2018, Otsuji Kanako, Japan’s first lesbian Diet member, tweeted the following response:

“In her article in Shinchō 45, LDP member Sugita Mio questions whether taxpayers’ money should be spent on ‘unproductive’ LGBT couples. I want to point out that LGBT people pay taxes too. At the risk of stating the obvious, every human being has value simply by being alive.”

杉田水脈自民党衆議院議員の雑誌「新潮45」への記事。LGBTのカップルは生産性がないので税金を投入することの是非があると。LGBTも納税者であることは指摘しておきたい。当たり前のことだが、すべての人は生きていること、その事自体に価値がある。 pic.twitter.com/5EbCaMpU9D

— 尾辻かな子 (@otsujikanako) 2018年7月18日

Retweeted over 10,000 times, Otsuji’s message went unexpectedly viral and sparked debate over the piece, in which Sugita had said that she did not believe that LGBT individuals actually faced significant discrimination, in addition to questioning whether taxpayers’ money should be spent on a group that does not have children and is therefore unproductive.

“Sugita has misunderstood a lot.” Otsuji says, “She claims that LGBT individuals do not face significant discrimination, when Japan does not allow them the option of getting married or making any legal guarantees toward each other. For this reason, LGBT individuals are unable to inherit, and individuals who have same-sex weddings overseas are ineligible for a spousal visa. While Japan’s Human Rights Bureau within the Ministry of Justice did set forth 17 ‘priority awareness-raising’ areas for the current fiscal year, including women, children, abduction victims, sexual orientation, gender identity, and homelessness, no national budget has been earmarked for LGBT issues. In any case, it is a broader legal framework that the LGBT community wants: the protection of its rights doesn’t cost money in the same way that, for example, public works do.”

On July 27, demonstrators gathered in front of LDP headquarters to protest the article. The next day, another group protested in front of Osaka Station calling for Sugita’s resignation. Dōshisha University Professor Okano Yayo, a specialist in political ideology and feminism, made a speech in which she came out as lesbian. Otsuji, who participated in the rally, recalls the moment.

“Okano told me that she wrote her speech out and rehearsed it thoroughly. She knew that she would tear up during it, because coming out as a lesbian would mean disclosing things about herself. Okano said that she condemned Sugita and the LDP because as a lesbian, she wanted to help those who were forced to put a lid on their feelings like she had to in the past. Saying that would have required a lot of courage. It was an expression of restrained anger.”

A young man who made an impromptu speech said that the article had an LGBT friend of his in tears, and condemned Sugita for writing it. “Sugita Mio hurt people who do their best in the face of prejudice,” Otsuji comments.

A demonstration outside Shibuya Station to protest Sugita Mio’s comments on August 5, 2018. (© Jiji)

Amid the furor, Sugita initially maintained her silence. Later, on October 24, she responded to questions from reporters inside the Diet. The following day she posted a statement on her website. While Sugita apologized in the statement for the misunderstanding and controversy caused by her inadvertent use of the word “productivity” and promised to “take seriously the fact that she made some people feel hurt or uncomfortable,” she has yet to apologize for or retract the article.

The Backlash Against Gender Neutrality

As Otsuji stated in her tweet, the Sugita article was a baseless attack on the LGBT community. Attacks of this nature are nothing new, and have a range of targets.

“Around the turn of the millennium, Nippon Kaigi (a conservative Japanese organization established in 1997) mounted an attack on gender neutrality, the movement to eliminate gender-based discrimination inherent in culture and society”, recounts Otsuji.

“Opposing gender-neutral education on the basis of the ridiculous argument that its proponents were trying to do away with gender distinctions and abolish the hinamatsuri festival for girls and tango no sekku celebration for boys, the group eventually succeeded in banishing the term ’gender-neutral‘ from government.”

In April 2005, the LDP established a project team chaired by then Acting Secretary General Abe Shinzō to perform a review of “gender-neutral education and extreme sex education.” Claiming to have confirmed that extreme sex education and teachings of an anti-family nature were being carried out under the pretext of gender neutrality, the group called for the term “gender” to be removed from the amendment to Japan’s Basic Plan for Gender Equality . The group did not, however, disclose the details of any of the 3,500 cases of extreme conduct they claimed to have identified.

However, the advent of Twitter, which made its Japanese debut in 2008, meant that the Sugita Mio case played out differently.

“On social media, Sugita’s ridiculous statements were put in the spotlight and called out for what they were”, Otsuji recalls. “Social media was also behind the protests at LDP headquarters and Osaka Station. Contrast that with 2010, when there was no large-scale protest in response to Tokyo Governor Ishihara Shintarō’s statement that gays and lesbians were somehow ‘deficient’, that the deficiency appeared to be hereditary, that they should be pitied as a minority, and that Japan had become too permissive in the way it allowed gay men to appear on TV.”

“This time, however, in addition to mustering solidarity through social media, we saw just how many people will join us in our action and our anger, and that is very encouraging,” continues Otsuji. “We should also take heart from the fact that the public in general now considers that to state that LGBT individuals cannot have children and are therefore unproductive is an abuse of their rights.”

Otsuji Kanako says that nobody is a member of the majority in every respect.

Everyone Is a Minority in Some Way

Otsuji describes the trend of using distorted facts to attack others as a new type of discrimination.

“We recently saw allegations that foreign residents were abusing Japan’s national health insurance scheme. I asked a question about the issue in the Diet, only be told that an investigation by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare into the total number of foreign residents using high-cost medical services identified only two cases in which services might have been provided to persons who did not have the proper residence status. And even those cases are unconfirmed.”

Attacks on those receiving public assistance are part of the same trend. In Japan, much fuss is made of benefit fraud, but little is made of the fact that the benefit take-up rate—that is, the percentage of those entitled to income support that actually receive it—is estimated to be a mere 20%. This means that income support is harder to receive than it should be, says Otsuji.

“I don’t think there is anyone out there who can say that he or she is a member of the majority in every respect,” she continues. “No matter who you are, it is likely that some aspect of you makes you a minority somehow. Alternatively, you might have a child who falls into that category. You might be young and healthy now, but everyone gets old eventually and we never know when we might get struck down by illness. If you keep attacking different minority groups, it will only be a matter of time before you are on the receiving end of such attacks yourself. In that sense, minority rights are something we confer not for the benefit of others but for our own peace of mind. People who distort facts and ignore the diversity already inherent in society in favor of looking for scapegoats do not solve anything.”

Speak Out and Make It “About You”

Following the reaction to Sugita’s article and the magazine’s October edition, Shinchōsha, the publisher of Shinchō 45, suspended its publication.

“The latest attack happened to target the LGBT community,” Otsuji says. “Shinchō 45 might have gone, but the bigots will simply choose a new forum for their next attack. Next time it might be a different minority that is targeted. We have to think about how we should respond to this trend.”

The now defunct Shinchō 45. At left is Sugita Mio’s article in the August 2018 edition. At right is the cover of the October edition, which contained a feature defending Sugita’s article. (© Jiji.)

She concludes, “If we think something is wrong, we need to say so, rather than waiting for someone else to act. Even if you can’t share your message publicly, at least share it with people you can talk to. It’s hard for people to empathize with a debate about invisible rights for invisible minorities, but when you share your message with people you can talk to, the issue being debated stops being ‘someone else’s problem’. For example, in 2015, Ireland legalized same-sex marriage after a referendum. An Irish friend told me that the referendum result was due to voters considering the issue as if it affected them personally. And that’s why visibility is so important. Politicians won’t ignore public opinion. In Japanese society, those who don’t follow the prescribed path often find themselves at a dead end. If we change our social institutions to allow diverse lifestyles, however, we can make society better for everyone.”

(Originally published in Japanese on March 13, 2019. Reporting and text by Kuwahara Rika of Power News. Banner photo: Otsuji Kanako.)