Japan’s First Modern Enthronement: The Ceremonies for Emperor Taishō in 1915

History Imperial Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Prime Minister’s Role

The enthronement ceremony for Emperor Taishō set a precedent for all subsequent imperial accessions. Until then, emperors ascended the Chrysanthemum Throne in a private ceremony at the Imperial Palace. The Taishō ceremony was a publicly celebrated event that was attended by representatives from various countries. It also firmly established the centrality of the emperor in Japan under the Meiji Constitution.

Crown Prince Yoshihito (Emperor Taishō) circa 1908. (© Mary Evans Picture Library/Aflo)

The formalities for the Taishō enthronement were set forth in a 1909 ordinance, and the ceremony was held at the Kyoto Imperial Palace, in accordance with the prewar Imperial House Law.

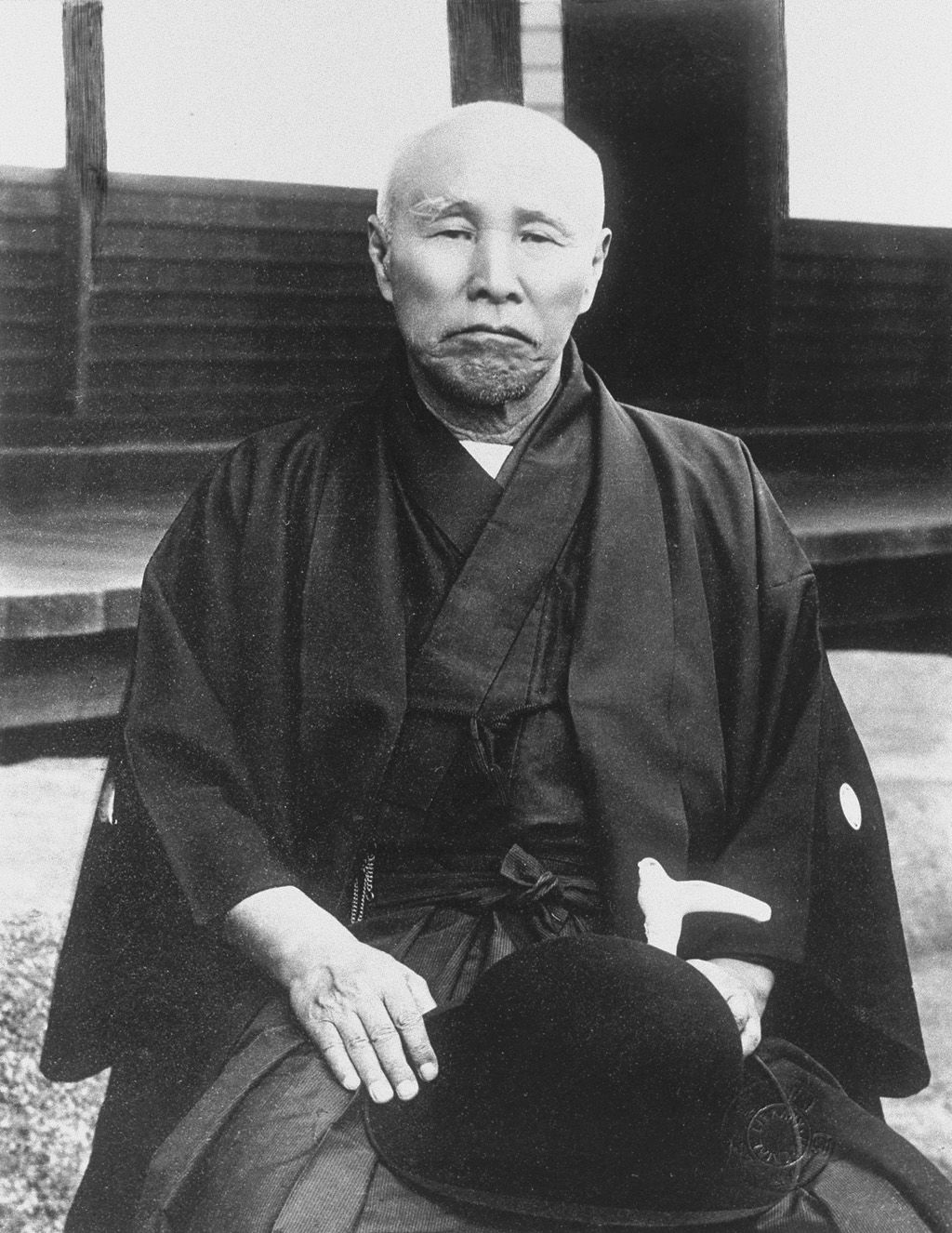

Presiding over the series of accession rituals, including the Daijōsai thanksgiving ceremony, was Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu. He returned to political life to lead the country in 1914 at age 76, having previously been prime minister for a short period in 1898.

Ōkuma founded Waseda University, which had very close ties to the imperial household, having received a large donation of ¥30,000 (equivalent to approximately ¥450 million today) from Emperor Meiji in 1908 in recognition of the university’s contributions to higher education. Emperor Taishō visited Waseda in 1912 while still crown prince and heard lectures in economics, law, and literature.

Prime Minister Ōkuma was an eloquent, genial man and met frequently with Emperor Taishō. The monarch enjoyed his company and would entreat him to stay a while longer even when the arrival of the next guest was announced.

Ōkuma Shigenobu. (© National Diet Library)

Participating in the emperor’s enthronement ceremony posed a great challenge for Ōkuma, however. He had lost his right leg at age 50 while serving as foreign minister when a bomb was thrown at him by ultranationalists. Donning ikan sokutai formal court attire, he needed to climb 18 steps up the main stairs leading to Kyoto’s Shishinden hall and then climb back down—without turning his back to the emperor.

This seemed an impossible feat for Ōkuma, who had a prosthetic leg, and some even called for his resignation, but he was determined to perform his duties and, with the help of his son-in-law, practiced going up and down the steps of the hall at the Kyoto Imperial Palace in full garb a month before the ceremony.

Enabling the Boy Prince to Attend

Another key figure in the enthronement ceremony was educator Sugiura Jūgō, who taught ethics to Hirohito following his graduation from Gakushūin Primary School in 1914. Among all the subjects that the young prince was taught, ethics—which groomed him to govern as a monarch—made the biggest impression on him. Sugiura was the principal of Daigaku Yobimon—the preparatory school for Tokyo Imperial University—and also of a private school that taught courses in English. Sugiura is attributed with imbuing the prince with the restrained dignity that became a hallmark of Emperor Shōwa.

Sugiura asserted that the boy be allowed to attend the Taishō enthronement ceremony, despite still being a minor, in view of his father’s ailing health. The imperial household minister and other political leaders opposed the idea, though, since Emperor Meiji had earlier expressed his opinion that members of the imperial family younger than 18—even if heirs to the throne—should not participate in official events.

Sugiura was not to be deterred, however, and made the rounds of influential officials to win them over, eventually prompting Emperor Taishō to allow his son to participate, no doubt so that he could see for himself what accession would entail.

Regarding the imperial transition, Sugiura taught the young prince that while he would, in effect, inherit the throne when the imperial regalia were passed down to him, he would also need to conduct stately, solemn rituals to report his accession to the imperial ancestors and more broadly to the general public and foreign countries.

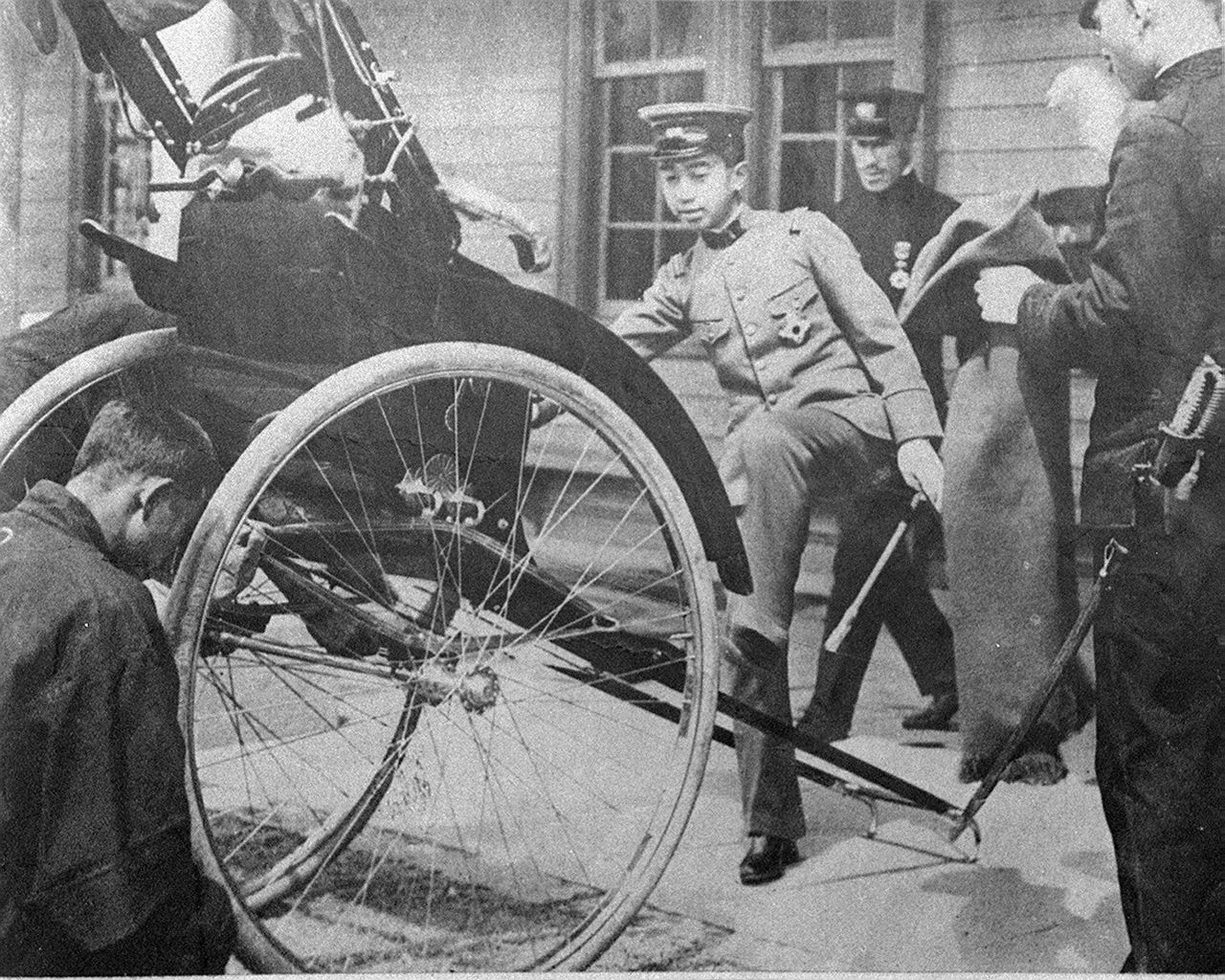

Emperor Taishō left Tokyo for his enthronement ceremony in Kyoto on November 6, 1915. Empress Sadako was pregnant at the time and did not accompany the emperor. Hirohito departed the following day, spent a night in Shizuoka, and arrived at the Nijō Imperial Villa on November 8. He participated in a rehearsal the next day in preparation for the formal ceremony on November 10.

At the time, Hirohito had not yet been officially designated crown prince, so he wore a simple court dress and headwear designed for imperial youths. In a morning ceremony, the emperor reported his enthronement to his ancestral deities and was conferred the sacred mirror as part of the imperial regalia.

Fourteen-year-old Hirohito mounts a jinrikisha in the Saga district of Kyoto on April 7, 1916. He is wearing the uniform of an army lieutenant. (© Yomiuri Shimbun)

Over 2,000 Guests

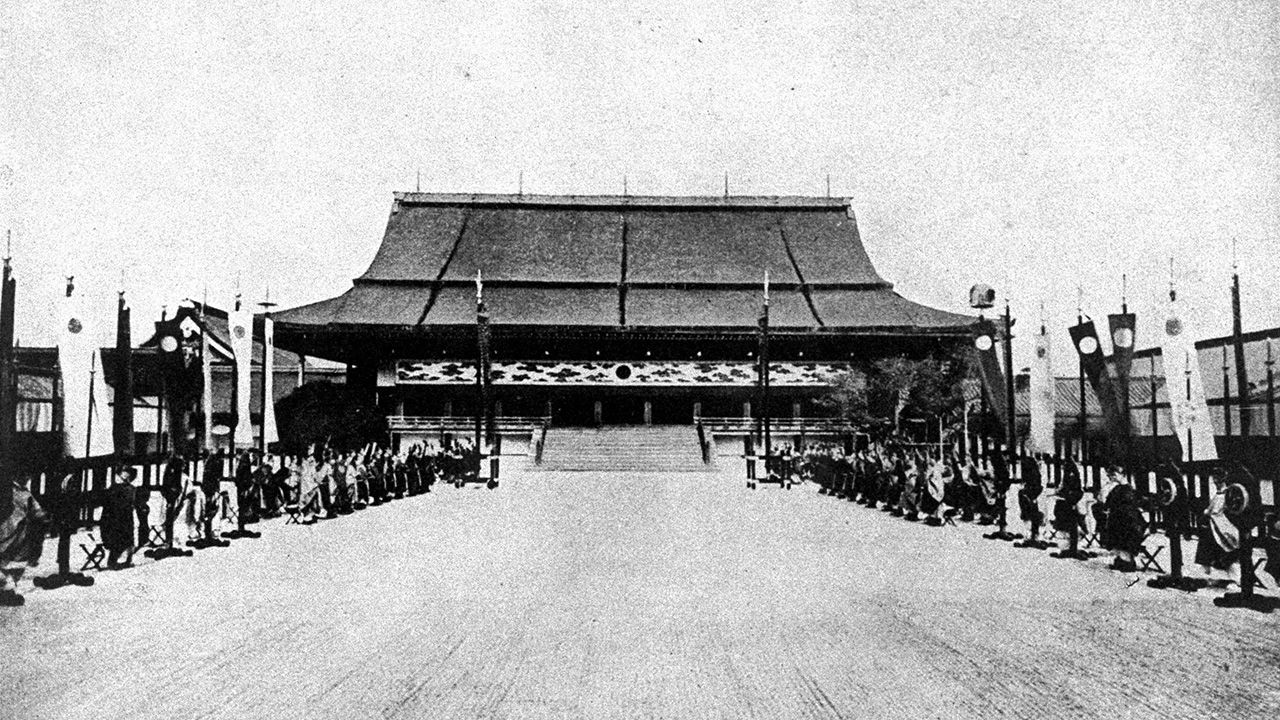

The main ceremony at the Shishinden hall was attended by over 2,000 guests, including imperial family members, political leaders, and ambassadors and other representatives from such countries as the United States, Britain, France, Russia, and Italy. In the courtyard stood 26 colorful banners in two rows. One banner featured the characters for “banzai” embroidered with gold thread, and others were decorated with motifs drawn from Japan’s legendary first emperor, Jinmu, such as a sake jar, ayu (sweetfish), and the three-legged crow, Yatagarasu. Lending pageantry along with the banners were men in traditional robes holding ceremonial items like swords, bows, and shields.

Inside the hall was a brand new Takamikura throne platform, built especially for this occasion. The Takamikura used by Taishō’s grandfather, Emperor Kōmei, was destroyed in a fire in 1854, so Emperor Meiji, at his enthronement in 1868, used the Michōdai, which is usually reserved for the empress. The Takamikura and Michōdai built for the Taishō enthronement have been used in all subsequent ceremonies.

At shortly after 3 pm, Emperor Taishō ascended to the Takamikura wearing a ryūei-no-kanmuri headpiece and sokutai robes dyed reddish-brown with the fruit of the haze (wax tree). He delivered an address proclaiming his accession, written in difficult Sino-Japanese kango style, conveying his wishes for the peace and happiness of people both in Japan and throughout the world. The practice of the emperor personally making such a proclamation at his enthronement began with Emperor Taishō.

Cheering Five Minutes Early

Prime Minister Ōkuma, also clad in court attire, listened to the address from the courtyard before mounting the 18 steps with the help of an assistant to deliver his congratulatory remarks on behalf of the people, referring to himself as a subject of the monarch four times in an expression of his loyalty. He then climbed down backwards so as not to turn his back to the emperor, and led the assembled guests in three cheers of “Banzai!”

The prime minster was scheduled to lead the cheers at 3:30 pm, and the entire nation was to join him then in wishing the new emperor long life. Because of the difficulty Ōkuma had in moving up and down the steps, however, it was already 3:35 when he shouted “Banzai.” This was an era without live television and radio broadcasts, so the nation wound up cheering the enthronement five minutes earlier than those attending the ceremony.

The young Hirohito observed the 30-minute spectacle from near the Takamikura, thinking, no doubt, of the day when he, too, would ascend the throne. After the ceremony, Ōkuma expressed his joy by proclaiming that the event marked the first time in Eastern history that representatives from countries around the world had gathered for an imperial enthronement.

The following day, Hirohito inspected the Ōmiya Palace, where the Daijōsai thanksgiving ceremony was to take place, and returned to Tokyo on November 13. He met his mother the next day to report on the ceremony in Kyoto and, upon learning that Prime Minister Ōkuma was unable to leave home due to his leg’s condition after the journey to Kyoto, Hirohito sent a basket of fruits as a get-well gift.

The Shishinden hall and Dantei (South Garden) of the Kyoto Imperial Palace, where Emperor Taishō’s enthronement ceremony was held. The Takamikura and Michōdai platforms, used in Tokyo when Emperor Naruhito and his father, Akihito, ascended the throne, are normally kept here in Kyoto. Photographed in April 2018. (© Jiji)

Breaking with Precedent

Emperor Taishō subsequently fell seriously ill, and Crown Prince Hirohito was named sesshō (regent) at age 20. Considering the turn of events, having the young prince attend the grand enthronement ceremony with guests from both Japan and abroad was as an act of great foresight.

Citing this precedent, some have argued that young imperial family members should have attended the most recent enthronement for Emperor Naruhito. Tokoro Isao, professor emeritus of Kyoto Sangyō University and a specialist in the cultural history of the imperial household, had this to say at a press conference on the imperial succession: “It would have been desirable for [13-year-old] Prince Hisahito and [17-year-old] Princess Aiko, who are both over 10, to attend the ceremony as well. I believe that the government should have given greater thought to having them participate for the sake of the continuity of the imperial family” (as reported by the Tokyo Shimbun, March 9, 2019).

I could not agree more. The government maintains that its decision was based on precedent, but an exception was made as recently as the enthronement of Emperor Taishō. Having the two young imperial family members attend would have been of great benefit to both and would no doubt have brought even greater joy to the people of Japan.

(Originally published in Japanese on October 18, 2019. Banner photo: The Shishinden hall and South Garden of the Kyoto Imperial Palace on the day of Emperor Taishō’s enthronement ceremony, November 10, 1915. © Mainichi Shimbun/Aflo.)

emperor imperial family imperial succession Emperor Taishō Emperor Shōwa