Securing the Succession: The Historical Role of Japan’s Imperial Family Cadet Branches

Imperial Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Reserve for the Imperial Family

Shortly before the Tokyo Olympics in the autumn of 1964, the Hotel New Otani opened in the Japanese capital; at the time, it was one of Asia’s largest hotels. It stood on what was formerly the site of the palace of the imperial family’s now defunct Fushimi cadet branch. The residence had stretched over some seven hectares, and vestiges of those days can still be seen in the hotel garden.

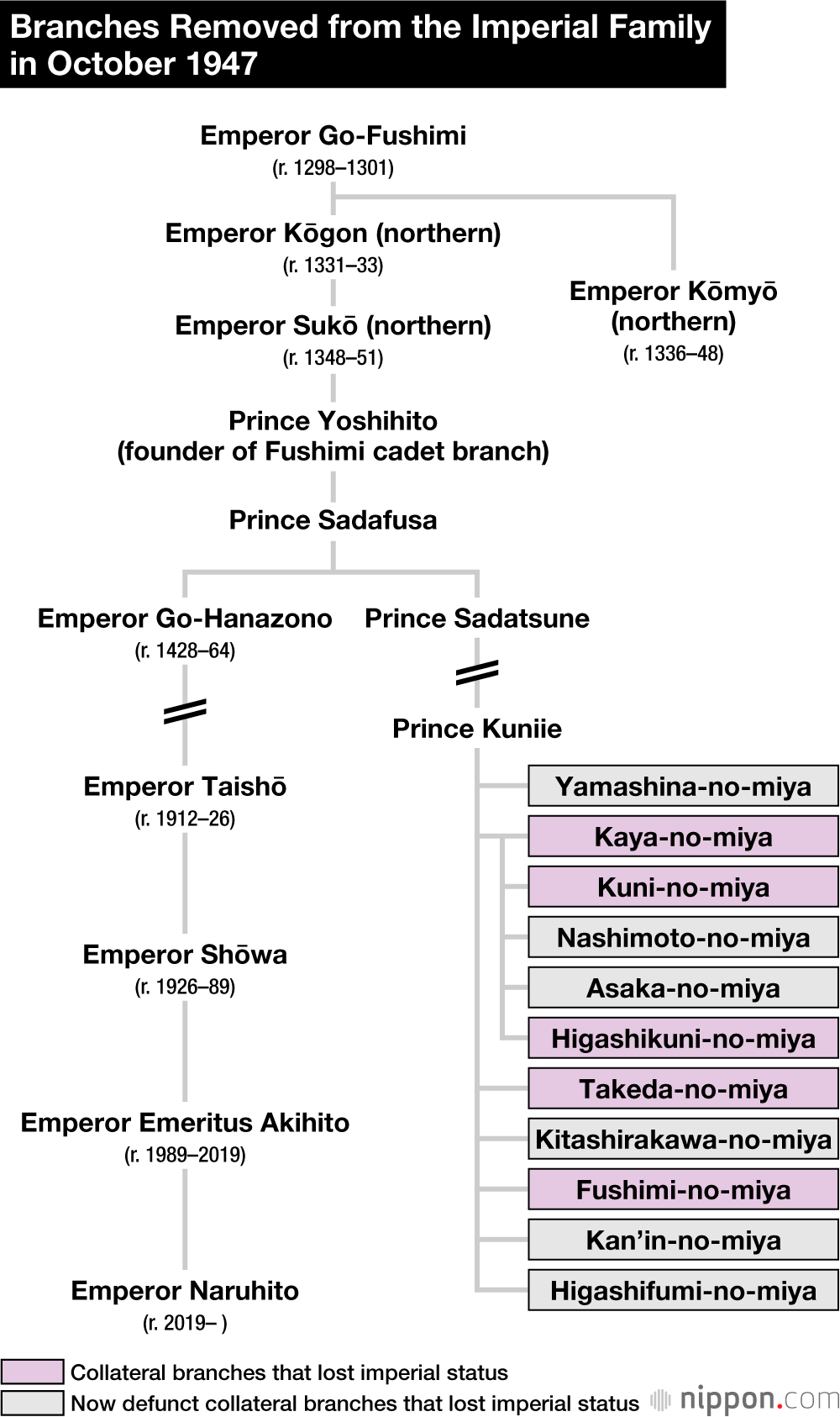

The Fushimi was the oldest of the imperial family’s four cadet branches. It was founded by Prince Yoshihito (1351–1416), the eldest son of Emperor Sukō, who ruled the Northern court during the period of the Northern and Southern courts (1336–92), when there were separate claimants to the imperial throne. The Fushimi branch continued to act as a reserve for the imperial family for more than 600 years until it was abolished in postwar reforms. Its current head, Fushimi Hiroaki, who is 90 years old, became an ordinary Japanese citizen in 1947.

Through the generations and centuries, the Fushimi has been a cadet branch with some of its members granted special princely status. Three later cadet branches were formed: the Katsura, Arisugawa, and Kan’in. During the Edo period (1603–1868), these were known collectively as the four shinnōke (“princes’ families”).

Mutual Safeguards

The purpose of the cadet branches was to ensure that the imperial bloodline would continue; if there was no successor in the imperial family, the new emperor could be chosen from a cadet branch. Conversely, if the cadet branches had no successors, they could bring an imperial prince into the family. Thus, the two systems safeguarded each other.

Emperor Go-Hanazono (r. 1428–64) was the grandson of Prince Yoshihito, the founder of the Fushimi branch; when he became emperor, his younger brother Prince Sadatsune succeeded in the cadet branch. Later, the son of Emperor Momozono (r. 1747–62), Prince Sadamochi, took over as head of the Fushimi branch, demonstrating the close links between the families.

When there were three cadet branches, the scholar and politician Arai Hakuseki was concerned by the possibility of a break in the imperial line, and advocated for establishing a fourth one. This bore fruit when the Kan’in branch was formed in 1710, led by Prince Naohito, the son of Emperor Higashiyama (r. 1687–1709).

The Kan’in branch soon provided an imperial ruler, as Naohito’s grandson was adopted to became Emperor Kōkaku (r. 1780–1817) when Emperor Go-Momozono (r. 1771–79) died without male issue. He was chosen for being close in age to Princess Yoshiko, the baby daughter of Emperor Go-Momozono, to whom it was decided that he should marry. Emperor Kōkaku ruled for 37 years, and is the direct ancestor through the male line of all the monarchs up to and including Emperor Naruhito.

More than 50 Children

Men born into cadet families had to be specially adopted to become part of the imperial family, as those defined as shinnō imperial princes were either brothers or sons of the emperor. Among those who did not join the imperial family, many of the sons of cadet branches found employment as the head priests at major Buddhist temples.

In the nineteenth century, Prince Kuniie of the Fushimi cadet branch had more than 50 children, raising the family’s fortunes. Around the time of the Meiji Restoration in 1868, his sons successively relinquished their positions at temples and returned to secular life. This is thought to have been influenced by the desire among Meiji statesmen like Iwakura Tomomi to distance the imperial court from Buddhism.

On their return, the Fushimi sons lost the names they took on as temple heads, receiving new names as the heads of collateral branches, such as Yamashina-no-miya, Kaya-no-miya, and Higashifushimi-no-miya. Initially these were intended to last for a single generation, but they later became hereditary.

The Kan’in branch, which lacked successors, adopted another son of Prince Kuniie to continue its line. This was Kotohito, Prince Kan’in, who went on to become an army field marshal.

Exile and Pardon

One notable son of Prince Kuniie was Prince Asahiko, who was trained for the priesthood from an early age. However, his involvement in political activities brought punishment from the shogunate, and he was placed in home confinement. After he returned to secular life, he became close to Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the last shōgun, drawing the ire of imperial loyalists. This led to him being stripped of his princely rank and exiled following the Meiji Restoration. He was pardoned, however, in 1870, regaining status within the Fushimi branch, and in 1875 he was allowed to establish the new Kuni-no-miya collateral branch.

Prince Asahiko had 18 children, including nine sons. One succeeded to head the Kuni-no-miya branch and one to the Nashimoto-no-miya branch, while three others founded new collateral branches. In 1924, his son Kuniyoshi’s daughter married Crown Prince Hirohito (later Emperor Shōwa); the grandmother of Emperor Naruhito, she is remembered posthumously as Empress Kōjun.

Managing the Family Size

Under the former Imperial House Law, promulgated in 1889, the distinction of having some members only remaining in the imperial family for one generation was abolished. Instead, all descendants of the emperor and the imperial family would be hereditary members. By the end of the Meiji era (1868–1912), there were 13 collateral branches; the Katsura cadet branch had gone extinct, but the number of Fushimi collateral branches had increased. Overall, the rise in the total number of branches may have been caused by Emperor Meiji’s concerns about the succession due to the poor state of health of his son, the crown prince and future Emperor Taishō.

The increase, however, put some financial strain on the imperial family, and new legislation in 1920 was intended to limit its size to those close in blood to the emperor. By this time, apart from the emperor’s immediate relatives, the family consisted of descendants of Prince Kuniie, and the legislation would have removed all of them. However, special exceptions were made for the lines of the eldest sons in each of the branches down to Kuniie’s great-grandsons, while other members were downgraded into the aristocracy. This removed around a dozen members from the imperial family.

From the Meiji era, male imperial members were required to serve in the army or navy. The head of the Fushimi cadet branch Prince Sadanaru served as a field marshal in the army during the pre–World War II era, and his successor Prince Hiroyasu-ō held the same rank in the navy.

Defeat in World War II, however, and US occupation would bring major changes to the imperial family, including a great reduction in size. A second article will look at the postwar history of the collateral branches.

(Originally published in Japanese on April 18, 2022. Banner photo: The former Kuni-no-miya palace at University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo. © Pixta.)

emperor imperial family succession Emperor Shōwa Emperor Meiji