Tapping the Power of Fermented Foods

Food and Drink Science Health- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Amid the profound business slump triggered by the coronavirus pandemic, demand for one kind of food product is booming. Traditional Japanese fermented foods, including miso, lacto-fermented pickles, and aged rice vinegar, are flying off grocery shelves. What accounts for this new surge in popularity?

Harnessing the Power of Microorganisms

The biggest factor is doubtless the growing emphasis on healthy eating. Fermentation is a method of preserving food, but it also adds nutritive value, and it performs both functions naturally, without the use of chemical additives. Moreover, new research has validated the dietary role of fermented food, shedding light on its many potential health benefits. These considerations have spurred more and more Japanese consumers to give traditional fermented foods a try. Having tried them, they fall in love with their rich, complex flavors and occasionally funky aromas. In this way, people of all ages are returning to the “tried and true” foods that supported the Japanese diet prior to westernization.

But is there any scientific basis for the health claims swirling around fermented foods? Absolutely. In the process of fermentation, “functional microbes” act on the starches, sugars, and proteins in ingredients like soybeans, cereals, vegetables, fish, and milk. In the process, they produce a slew of important nutrients. They also synthesize compounds with the capacity to normalize blood pressure, suppress the formation of cancer cells, lower triglyceride levels, dissolve blood clots, improve liver function, and even guard against the effects of radiation.

Of particular interest nowadays is recent research suggesting that fermented foods can help support a healthy immune system. A healthy immune system is one that recognizes and attacks disease-causing viruses and bacteria (as well as rogue cancer cells), without going on a rampage and damaging healthy tissue. Special cells in the lining of the large intestine play a critical role in supporting this kind of balanced immune response, aided by a host of microorganisms. Among these friendly microbes are the lactobacilli (lactic acid bacteria) found in many fermented foods.

In the following, we will take a closer look at the potential health benefits of five traditional Japanese foods produced through fermentation: nattō, miso, rice vinegar, tsukemono (pickled vegetables), and narezushi (a kind of fermented fish).

Nattō

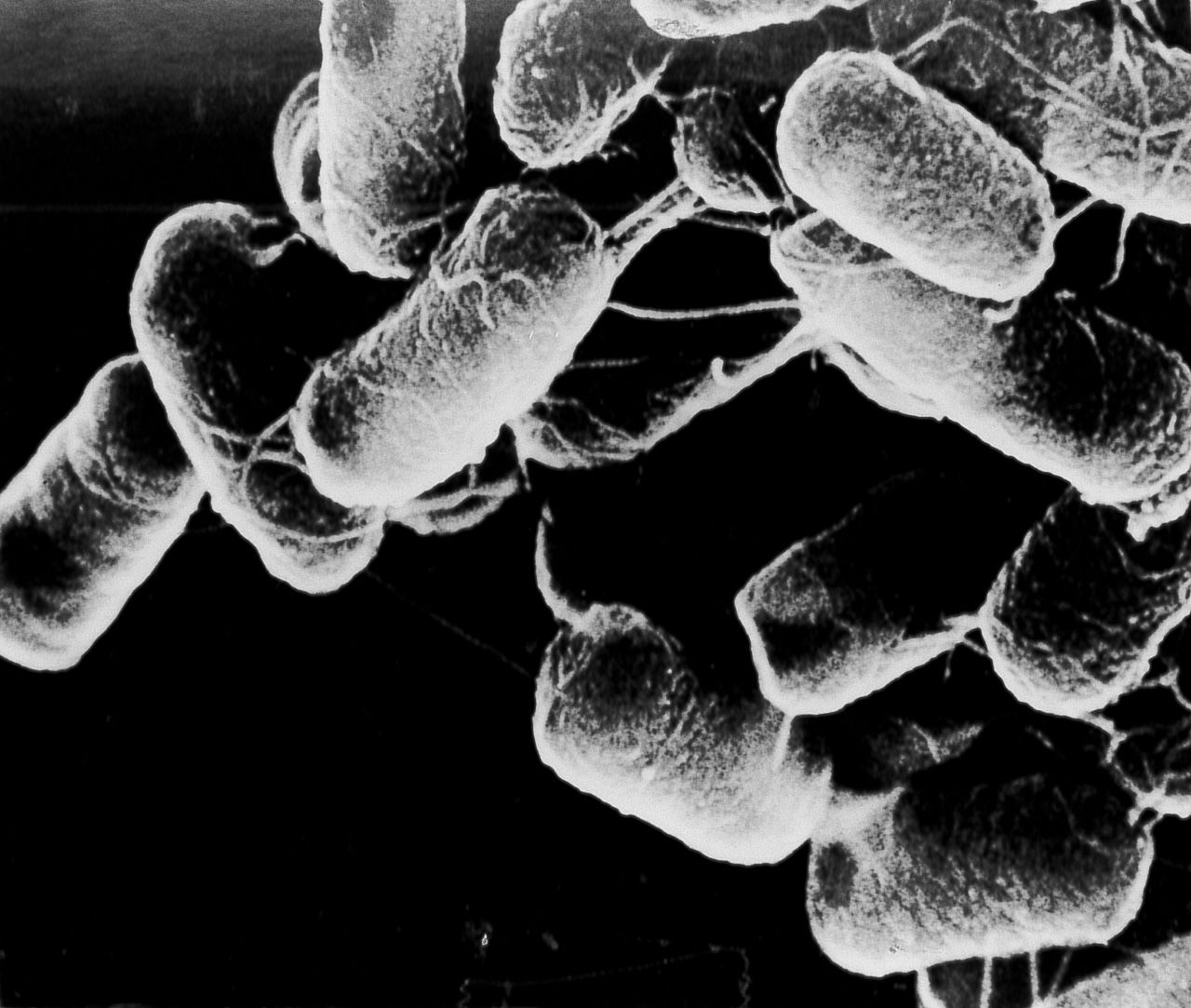

Bacillus subtilis nattō, the microorganism that turns steamed soybeans into nattō. (© Koizumi Takeo)

Nattō is a ready-to-eat product made by fermenting steamed soybeans with the help of a special strain of bacteria, Bacillus subtilis nattō, commonly known as nattō-kin. Through fermentation, these friendly microbes add greatly to the nutritive value of the cooked soybeans. Nattō is particularly rich in B vitamins, with 10 times the amount of vitamin B2 (riboflavin) as the same quantity of unfermented cooked soybeans. Vitamin B2 is essential for growth and overall health, playing a key role in energy production, fat metabolism, and cellular function. Similarly, the vitamin B1 (thiamin) in nattō is needed for energy metabolism and cellular function; a thiamine deficiency can lead to numbness, muscle weakness, loss of appetite, enlargement of the heart, confusion, and memory loss. The vitamin B6 is involved in amino acid metabolism and supports mental health, immunity, and healthy skin. Niacin (also known as vitamin B3) is needed to prevent pellagra, a disease characterized by severe digestive and neurological symptoms.

But the health benefits of nattō go beyond basic nutrition. Recent studies indicate that Bacillus subtilis can prevent the growth of toxic bacteria in the gut. It produces a unique and medically valuable enzyme called nattokinase, which has been found to degrade fibrin, the main component in blood clots. Nattokinase has been extensively studied and tested in Japan and other Asian countries and is already being used as an oral antithrombotic agent. In addition, nattō has been found to contain substances called ACE (angiotensin conversion enzyme) inhibitors, which lower high blood pressure and are also believed to modulate the immune response.

Nattō is very high in protein. Ounce for ounce, it contains about as much protein as ground beef. Levels of free amino acids (particularly essential amino acids) increase dramatically as a result of fermentation. High levels of glutamic acid, the main source of the taste component known as umami, give it its special savoriness. It is also a good source of calcium, phosphorus, and potassium and the richest known food source of vitamin K2, important for bone and heart health.

Miso

A map showing the many varieties of miso produced around Japan. (Photo courtesy of Koizumi Takeo)

Miso is a traditional fermented paste made of soybeans—often with the addition of rice or barley—salt, and kōji, a special mold culture. It is one of the five basic seasonings used in Japanese cuisine, along with sugar, salt, vinegar, and soy sauce. Miso making is a lengthy process that makes use of another functional microorganism, the fungus Aspergillus oryzae, which is cultured on steamed rice or other grains to create kōji. Miso has a deep, complex umami, thanks to months of fermentation and aging, and it can be used to preserve meat, fish, and vegetables. Miso is also high in protein, ranging from about 10% to as much as 19% (in the case of the dark, aged variety called mame miso). In Japan, it traditionally provided a valuable source of protein—particularly the essential amino acids lysine and leucine—as well as various vitamins and minerals that might otherwise be wanting in a diet centered on grains and starchy root vegetables.

Miso also contains dietary fiber, which can lower the risk of colorectal cancer, and high levels of oligosaccharides, “prebiotics” that encourage the growth of friendly bifidobacteria in the gut. It is packed with B vitamins, which (in addition to their basic functions, discussed above) reduce the risk of cancer and other lifestyle diseases through their antioxidant activity. An epidemiological study published in October 1981 by Dr. Hirayama Takeshi, then director of epidemiology at the National Cancer Center Research Institute, found lower rates of mortality from stomach cancer among subjects who consumed a bowl of miso soup on a daily basis. Daily miso consumption was also associated with lower rates of atherosclerosis, hypertension, gastric and duodenal ulcers, cirrhosis of the liver, and cancer at all sites. In addition, the fermentation process produces lecithin, which helps control high blood pressure. Other compounds found in miso have been shown to strengthen the immune system, protect against radiation, and suppress the action of substances that can trigger mutations and lead to the growth of tumors. Fermentation also removes most soy allergens from miso.

Tonjiru is a tasty and nutritious miso-flavored soup made with pork and root vegetables. (© Pixta)

Rice Vinegar

Kurozu rice vinegar matures in black ceramic jars in Fukuyama, Kagoshima Prefecture. The artisans adhere to traditional methods, leaving the liquid to ferment and age slowly in the sun. (© Ōhasshi Hiroshi)

Rice vinegar is another important food product made from fermentation. The Japanese people have been using rice vinegar in their cooking at least since the Nara period (710– 94), as we know from references in the Manyōshū poetry anthology (compiled c. 759) and other contemporary sources. Along with salt, sake, and soy sauce, it was one of four basic seasonings, known collectively as kusu, that were served with meals in small condiment dishes.

The Japanese have long regarded vinegar as a tonic that combats fatigue, and science supports this view. Muscle fatigue stems from the buildup of lactic acid, and studies have shown that substances in vinegar stimulate the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, which releases energy, and inhibit the conversion of pyruvic acid to lactic acid in the body.

Vinegar is also seen as an ally in the fight against diseases and conditions associated with aging. In a clinical test on patients with hypertension, those administered vinegar each day saw a reduction in overall cholesterol and triglyceride levels compared with the control group. In addition to its lipid-dissolving properties, vinegar can lower blood sugar and is believed to reduce the risk of diabetes. Vinegar is antihypertensive as well, thanks to a substance that blocks the action of angiotensin II (which causes blood vessels to constrict and raises blood pressure). Aged vinegar in particular is believed to have antioxidants that guard against cell damage from peroxidization, lowering the risk of cancer and protecting against liver damage. Many people recommend vinegar for weight loss as well.

Tsukemono (Japanese pickles)

An assortment of Yamagata pickles: From left, Yamagata seisai (mustard greens), eggplant, and red turnip. (© Pixta)

Japan is truly a pickle-lover’s paradise. It boasts 80 different types of daikon (giant white radish) tsukemono alone, and when one factors in all the different combinations of vegetables, pickling media, and seasonings, the varieties soar into the thousands. In recent years, the lowly tsukemono has taken on a new luster as a weapon in the arsenal against lifestyle diseases associated with a Western diet high in sugar, fat, and animal protein and low in fiber.

Tsukemono tend to be high in soluble fiber, which can lower cholesterol and prevent blood sugar spikes, thus helping to lower the risk of heart disease and diabetes. The insoluble fiber (found especially in leafy green vegetables) stimulates the intestines and other digestive organs and boosts insulin sensitivity. Together, they work to promote bowel health and reduce the risk of diabetes and colorectal cancer.

Narezushi

Funazushi, a fermented delicacy made with fish and rice, is a specialty of Shiga Prefecture and an acquired taste. (© Pixta)

For the adventurous, there is narezushi, a fermented product regarded as the progenitor of sushi. Unlike the familiar, modern-day form of sushi, narezushi (including funazushi, sabazushi, and sanmazushi) is a traditional fermented food made from steamed rice and salted fish.

Before the advent of refrigeration, fermentation was an important means of preserving food. But the fermentation process can also greatly enhance the food’s nutritional value, as we have seen. This certainly applies to narezushi, which is rich in vitamins, amino acids, and other nutrients. The active lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria in narezushi are friendly microbes that prevent spoilage by putrefactive bacteria. They also function to create an environment hostile to toxic bacteria inside the gut. Like vinegar, narezushi is believed to fight physical fatigue. It is recommended for constipation and high blood pressure and is thought to have a salutary effect on the immune system, helping to ward off colds and other viral infections.

(Originally published in Japanese. The author enjoys a bowl of nattō with rice. Photo courtesy of the author.)