Report from Hiroshima: 75 Years Later

Fight for Recognition: The Long Ordeal of “Black Rain” Survivors

In-depth Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In Japan, anyone certified as a survivor of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or hibakusha, can receive free health care and other government benefits under the Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Assistance Act. The special “hibakusha health handbooks” issued to certified survivors function as supplementary health insurance cards, entitling the bearers to periodic physical examinations, screenings, and medical treatment.

But even now, many survivors of the atomic bomb are denied those benefits, despite having been exposed to radioactive fallout in the form of “black rain.”

A section of plaster wall bearing the traces of black rain. (Courtesy of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

Haunted by a Blackened Shirt

Honke Minoru, 80, still lives in his birth home in what is now Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward in the hills northwest of the city proper. His village was about 19 kilometers from the A-bomb’s hypocenter. On the morning of August 6, 1945, he was with his mother and younger brother on the veranda of the family farmhouse, watching two farmers bind sheaves in a neighboring wheat field.

“Suddenly, there was a flash and a big boom like thunder,” he recalls. “A gray cloud billowed up from the hills, and the sky got dark. After a while, what looked like burnt scraps of newspaper started to drift down from the sky. The men next door said that something must have happened in Hiroshima, and they told us not to touch any of the trash flying around, since it could be dangerous.”

Honke Minoru near his home in Yukichō in Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward. (Photo by Dōune Hiroko)

Later, as Honke and his brother played outside, the sky turned black, and it began to rain. As they went inside, he noticed that the rain had left dark stains on his brother’s shirt.

“I’ll never forget that,” says Honke. “I was exposed to the black rain. I grew up drinking water that ran down from those mountains and eating vegetables that were watered by it. As a child, I had nosebleeds all the time. Sometimes, when I was washing my face in the morning, my nose would bleed and bleed and wouldn’t stop. Yet the government just drew a line on a map, without even conducting a proper survey. How can we accept that?”

An Arbitrary Demarcation

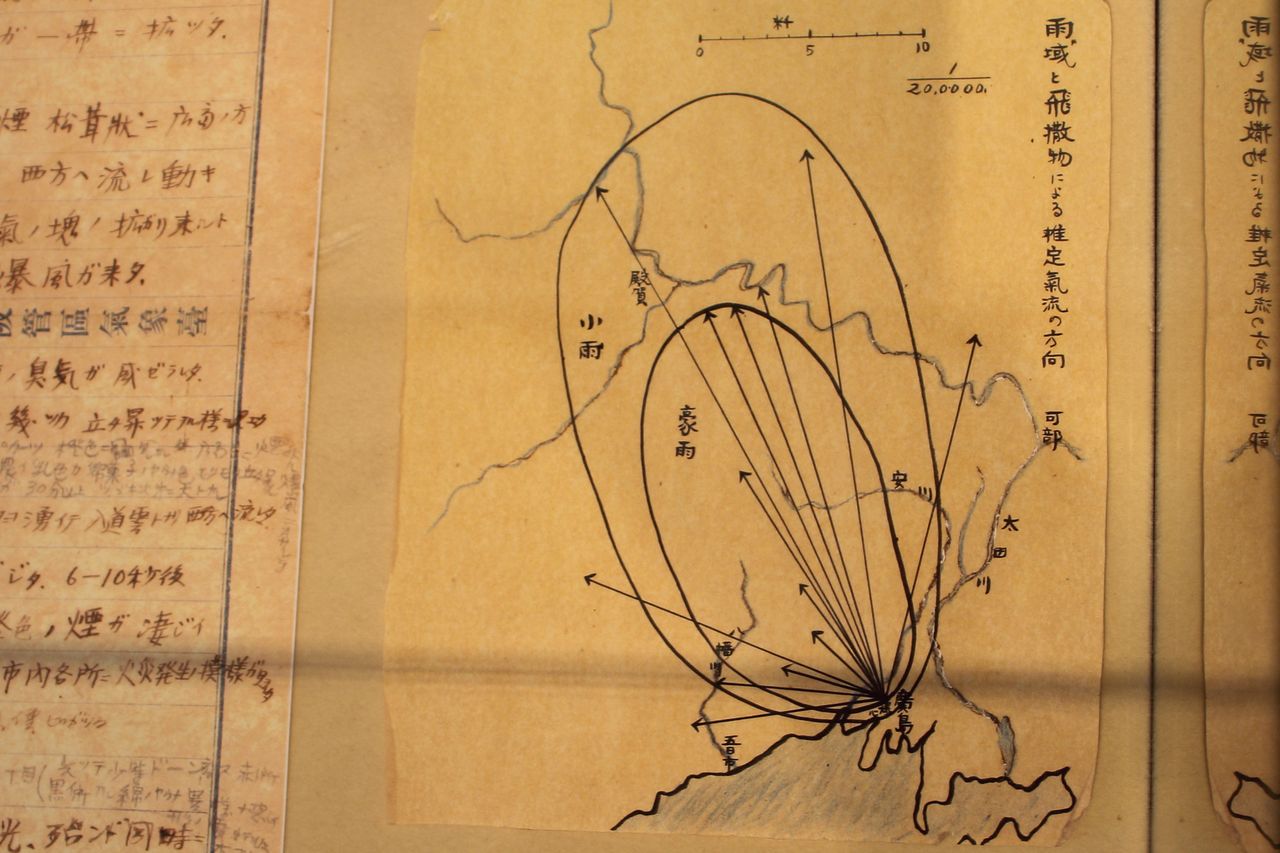

In 1976, the Japanese government instituted a new program extending medical benefits to “black rain” survivors outside the previously established radiation exposure zone. However, eligibility was restricted to those inside the “heavy rain area” of a rainfall map that had been drawn up years earlier by local meteorological officer Uda Michitaka and his staff on the basis of a survey conducted in the bombing’s aftermath. People within the designated area became eligible for free physical examinations, cancer screenings, and other diagnostic tests and were issued hibakusha health handbooks if diagnosed with any of a number of specified ailments, including cancer, leukopenia, and cataracts. Anyone outside, in the “light rain area,” was denied those benefits.

Rainfall map delineating the extent of the black rain after the bombing of Hiroshima, based on a survey conducted by the Hiroshima District Meteorological Observatory. (Ebayama Museum of Meteorology, Hiroshima)

The system was controversial from the start. In some cases, the line separating the “heavy” and “light” rainfall zones cut right through a village or neighborhood. Honke’s community was a case in point. Everything to the south of the Minochi River was included in the “heavy rain area,” while all the homes on the north bank—including Honke’s—were excluded. Honke notes that in some cases, the approval or denial of benefits depended on the route a child had taken walking home on the day of the bombing.

Honke Minoru points to the area south of the Minochi River, whose residents were made eligible for hibakusha healthcare benefits in 1976. Those living on the right bank—including Honke’s residence—remained ineligible. (Photo by Dōune Hiroko)

“My mother developed cataracts and glaucoma and lost her sight,” says Honke. “Then she died of gallbladder cancer. I’ve had three operations for cataracts, and now I have glaucoma. Naturally I wonder how much of this is the result of radiation exposure. Everyone around here talked about the black rain, but the government never sent anyone to interview us.”

New Survey Results Ignored

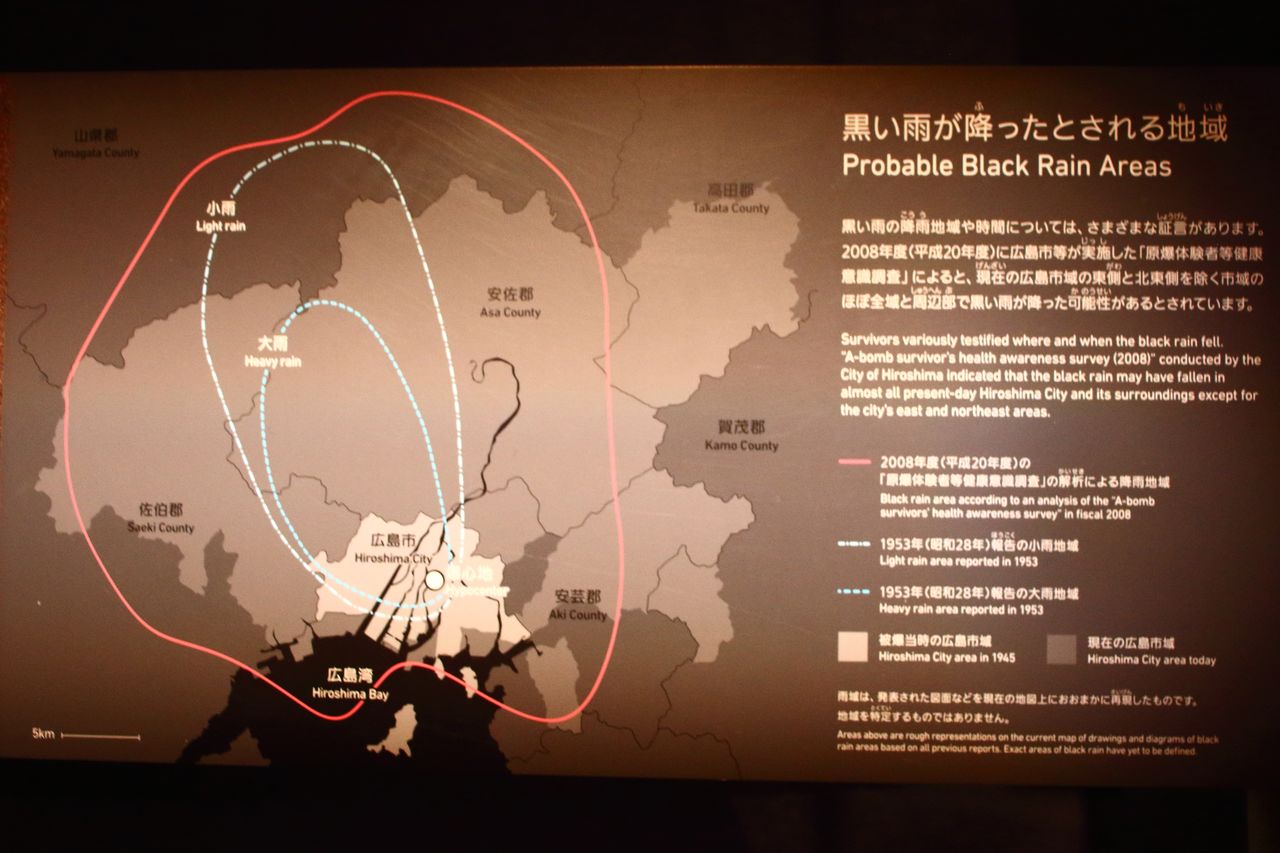

In the late 1980s, Masuda Yoshinobu, a retired official with the Japan Meteorological Agency, presented the results of his own research, which concluded that the black rain fell over a wider area than previously assumed. Between 2008 and 2010, Hiroshima Prefecture and the city of Hiroshima surveyed local residents to determine the health impacts of the bomb. Analyzing more than 30,000 completed questionnaires, experts drew up a new rainfall map showing significant black rain across an area about six times larger than the designated zone.

In 2010, on the basis of this survey, the governor of Hiroshima Prefecture and the mayors of Hiroshima and seven nearby municipalities petitioned the central government to extend hibakusha benefits to a much wider area. (They have not changed their position; on the “black rain” map on display at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the expanded zone stands out sharply, demarcated with a bold red line.)

The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare set up a panel to study the request, but in 2012 it announced that it would not expand the boundaries of the black rain area.

“Black rain” exhibit at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Ultimately, the residents of the excluded area decided to take their case to court. In 2015, a group of 88 citizens filed a class-action lawsuit with the Hiroshima District Court, demanding the same healthcare benefits granted other hibakusha. By then, seven decades had passed since the bombing of Hiroshima.

“I Am a Hibakusha”

One of the leaders in the fight to expand the boundaries of the black rain zone is Takatō Seiji, 79, another resident of Saeki Ward. A former high school teacher, Takatō became involved in the cause in 2002, when he retired. That year, a former classmate of his came to him to share her concern about the large number of local residents who seemed to be dying of undiagnosed ailments. The two of them undertook to call on ailing citizens in the former village of Yawata, about nine kilometers west of ground zero.

“Lots of people we visited had pretty much lost the will to live,” Takatō recalls. “One of the men we saw turned us away, saying, ‘Listen, I’m never going to get better, and I can’t afford to go to the hospital anyway, so just leave me alone!’ It was a great shock.”

Asking around, Takatō confirmed that black rain had indeed fallen on the village after the bombing. But because it was located just outside Uda’s “heavy rain area,” residents were denied hibakusha health handbooks and had given up hope of getting appropriate medical care.

It was then that Takatō decided to fight for expansion of the designated black rain zone. He founded a citizens’ advocacy group, the Saeki Ward Black Rain Association. More than 100 community members attended the group’s launch, testifying to widespread concern about the long-term effects of exposure.

Ironically, Takatō himself has no memory of the black rain. He was four years old at the time, also in a village just west of the designated “heavy rain area.” He remembers seeing a flash, hearing a boom, and watching as the skies over Hiroshima reddened and darkness fell around them. But he admits that he remembers almost nothing of what followed.

Takatō was rather sickly as a child and had to have surgery for a swollen lymph node, but since he experienced no major health problems for years afterward, he gave little thought to the health risks of nuclear fallout. As he explained in his testimony for the class-action suit, he only began to think of himself as a hibakusha decades later, when he interviewed a neighbor who had been 14 years old at the time of the bombing. She had told him how she had hurried home from school in the semi-darkness, brushing falling ashes, cinders, and debris from her school uniform. “Listening to her, I realized that in all likelihood I too had absorbed radiation from that fallout.”

Takatō Seiji. (Photo by Nippon.com)

In the spring of 2019, Takatō was diagnosed with hypertensive heart disease and spent two weeks in the hospital after suffering a minor stroke. At the start of this year, he was hospitalized again with arrhythmia. Hypertensive heart disease is among the disorders listed as “possibly linked to radiation exposure” under the Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Assistance Act.

These health crises have deepened Takatō's sympathy with the plight of Japan’s aging A-bomb survivors and confirmed his own sense of identity. “I am a hibakusha,” he says, “and I’m determined to see our lawsuit through to its conclusion.”

Justice Delayed

From the beginning, a central focus of the “black rain lawsuit” was the validity of the government’s demarcation of the eligibility zone. “There’s no sound basis for restricting healthcare benefits to people in the heavy rain area to start with,” argues attorney Takemori Masayasu, who leads the plaintiffs’ legal team. “Furthermore, the ‘Uda study’ that provided the basis for the government’s demarcation was carried out under serious physical and time constraints. In the turmoil that followed the bombing, there was no way they could survey the outlying areas where the plaintiffs were located.”

Takemori seemed confident of a favorable ruling. “However you look at it, the victims of black rain were vulnerable to the health impact of ionizing radiation from the atomic bomb,” he said. “Given the intent of the Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Assistance Act, it’s clear that the plaintiffs should be covered by healthcare benefits.”

Lawyers for the two sides concluded their oral arguments in January 2020. By then, 13 of the original 88 plaintiffs had died. Another 3 died in the months that followed. The 72 that survive range in age from 75 (four months old when exposed) to 96.

On July 29, Judge Takashima Yoshiyuki of the Hiroshima District Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and ordered authorities to recognize the group as hibakusha, bringing their long struggle for acknowledgement to an end.

The number of hibakusha health handbook holders peaked in 1980 at approximately 372,000. As of March 2020, there were just 136,682 remaining, and their average age was 83.3. The ruling, however, puts pressure on the government to extend health benefits to other long-neglected groups of hibakusha.

The “black rain lawsuit” is by no means the first legal action carried out on behalf of Japanese A-bomb survivors in the decades since World War II. But it may well be the last.

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting and text by Ishii Masato of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Plaintiffs and supporters in the “black rain lawsuit” celebrate their victory outside the Hiroshima District Court on July 29, 2020. © Jiji.)