Historical Landmarks of the Kamakura Lords

Exploring the Hōjō Era at the Kamakura Museum of History and Culture

History Culture Travel Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Wealth of Knowledge on Display

The Kamakura Museum of History and Culture stands in Ōgigayatsu, a tranquil, upmarket suburb of Kamakura. The building, designed by the studio of British architect Norman Foster as a holiday home for a prominent business leader, was donated to the city and redeveloped for the museum, which opened in 2017. Embellished with artificial marble and ample natural interior light thanks to large windows, the beige, low-rise structure blends into its surroundings. Many architects visit just to appreciate the building.

The Kamakura Museum of History and Culture viewed from the rear garden. (© Mochida Jōji)

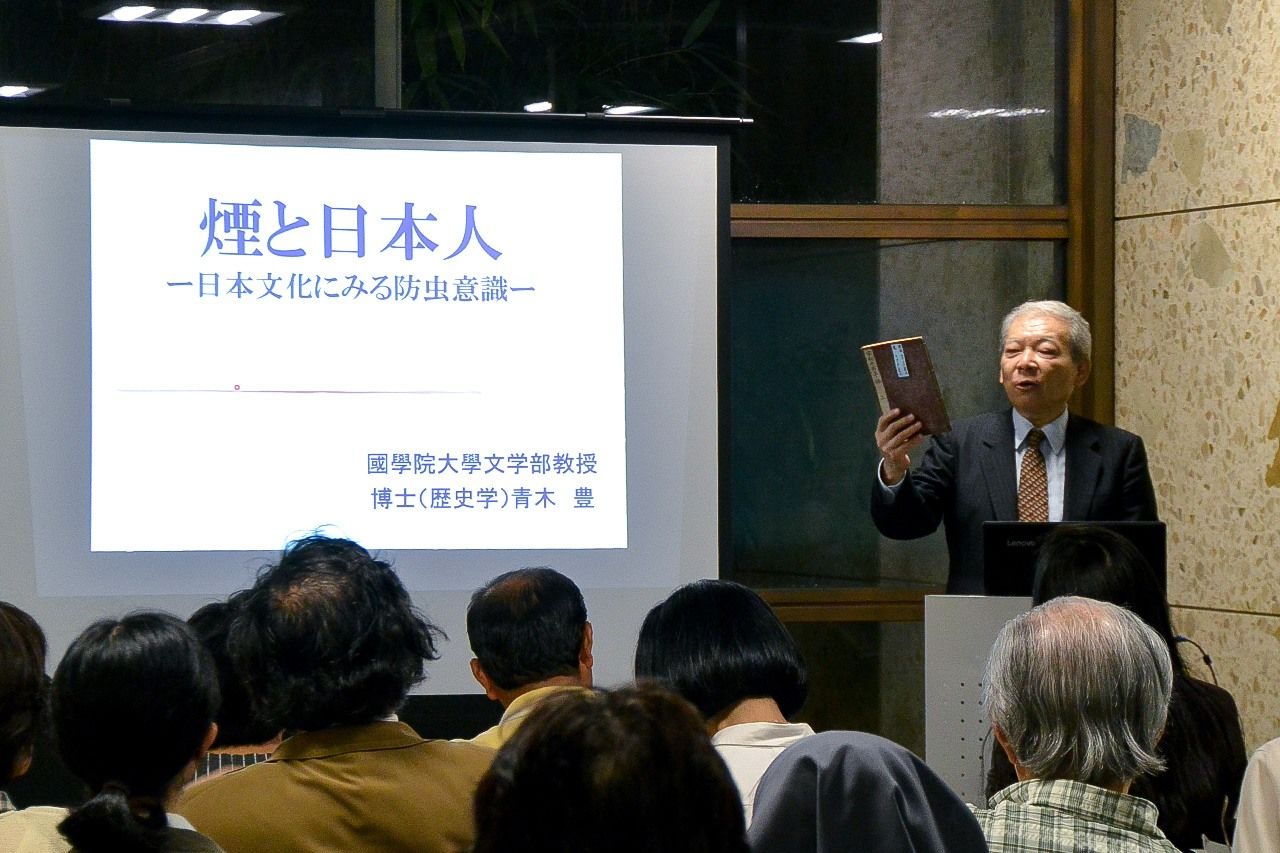

Kamakura is an ancient capital with many historical structures and relics. The city’s Board of Education records and analyzes archaeological excavations, and the museum functions as a municipal facility to share discoveries with the public. Because the building was originally a residence, it is undeniably cramped as a museum, with just three exhibition rooms in the main building and one in the annex. The museum’s head, Aoki Yutaka, a former professor at Kokugakuin University, believes that they must therefore put more effort into educational activities to compensate.

Museum head curator Aoki Yutaka giving an evening lecture. (Courtesy of the Kamakura Museum of History and Culture)

Each Saturday, curators give commentary on exhibits; the museum also hosts talks from the head of a local Buddhist temple and night courses on topics such as “reading historical documents” and “interpreting picture scrolls.” There are children’s workshops, such as one for “understanding incense,” and the staff give talks at schools. Their educational program is impressive, though it has mainly been placed on hiatus because of COVID-19.

Curator Ōsawa Izumi (center) giving a talk at the gallery in pre-COVID days. (Courtesy of the Kamakura Museum of History and Culture)

Although the museum has held few events recently, in February 2022, it hosted a symposium entitled “The Era of Hōjō Yoshitoki.” It was organized together with cultural property researchers from the city of Izunokuni, Shizuoka Prefecture, once the home of the Hōjō clan, who helped Minamoto no Yoritomo to raise his army.

Extracting Information from Artifacts

We often speak of “excavation,” but in a modern city, with complex infrastructure, residents, and businesses, opportunities to dig are limited. Consequently, we do not yet have an overall picture of the “city of the samurai” that was once Kamakura. In the precincts of the municipality, landowners in areas where cultural artifacts may be buried are obliged to allow an archaeological survey prior to any redevelopment.

If ancient building foundations are discovered, the city officials make a detailed record, taking photographs and accurate measurements. But unless it contains nationally or locally designated historical ruins, the site is returned to the landowner, in whose hands its fate rests.

According to Aoki, the museum head, development is the antithesis of preservation, but the valuable records the city officials obtain are handed to the museum, including comprehensive reports and excavated fragments and artifacts. Thereafter, scholars are able to examine the artifacts.

When asked about the significance of exhibitions, Aoki responds, “The relics and ruins are an inexhaustible wealth of information. Research enables us to extract information from them, whereby we can convey historical implications to the public. But we also must create exhibitions that are visually appealing.”

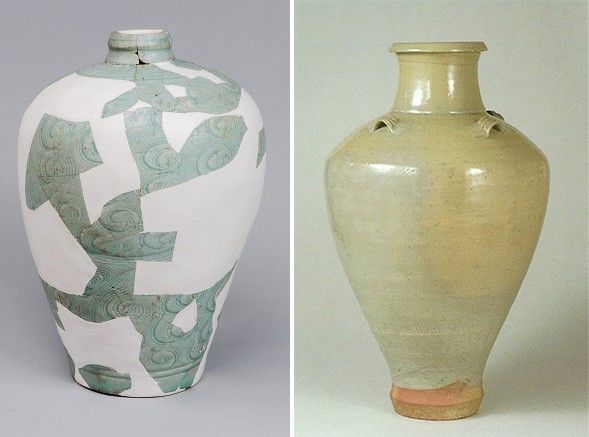

The museum’s permanent display features ceramics, including relics from Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1271–1368) dynasty China, and Seto, Tokoname, Atsumi, and other Japanese ceramic wares, indicating the extent of Kamakura’s maritime trade with these regions. A prized possession is a porcelain jar discovered intact in a grotto tomb during excavation of the ruins of the temple Shinzenkōji.

A celadon sake jar excavated from the ruins of a samurai mansion (left) and a four-handle porcelain jar uncovered from the ruins of Shinzenkōji. (Courtesy of the Kamakura Board of Education)

The Work of a Curator

The museum has four curators, who expertly match artifacts with data from archaeological remains and historical records to glean relevant information. One of them, Ōsawa Izumi, says she wanted to work in the field of history—and especially the Kamakura period—ever since she was young, making this a dream job for her. In 2019, she coordinated an exhibition about Kamakura cuisine in the medieval period. Many excavated items are actually waste materials from day-to-day life, with many pertaining to food. Ōsawa herself loves eating and drinking, which inspired her to pursue this familiar theme.

Part of a 2019 exhibition highlighting the cuisine of medieval Kamakura. (Courtesy of the Kamakura Museum of History and Culture)

Excavations at former samurai residences uncovered many abalone shells and fish bones. Ōsawa explains that they give insight into the food culture as well as the society and economy. “The abalone were all enormous. They weren’t something you’d harvest for a regular meal: a supplier would have gathered those that met their specifications, to sell to upper-class samurai. It’s crucial to understand the economy and distribution that underpinned the city, whose population numbered in the tens of thousands.”

Many shallow earthenware sake cups have been unearthed, evidence that samurai often held banquets. “At the time, single-use tableware had spiritual meaning, indicating something was unsullied,” explains Ōsawa. “It was commonly used at formal drinking parties.” Kamakura saw greater prosperity after the 1221 Jōkyū War, when Hōjō Yasutoki extended control over the western provinces. It is understood that urbanization had progressed, in contrast to the rural landscape when Yoritomo first arrived in 1180.

The Hōjō Exhibition

In 2022, the museum has planned exhibitions relating to the Hōjō to coincide with the screening of NHK’s new historical taiga drama serial Kamakura-dono no 13-nin (The 13 Lords of the Shōgun). The first installment, “From Izu to Kamakura,” which ended on March 26, was chiefly directed by curator Yamamoto Minami, a young researcher who attracted attention with her recent biography of Hōjō Yoshitoki, Shiden: Hōjō Yoshitoki (Historical Materials on Hōjō Yoshitoki).

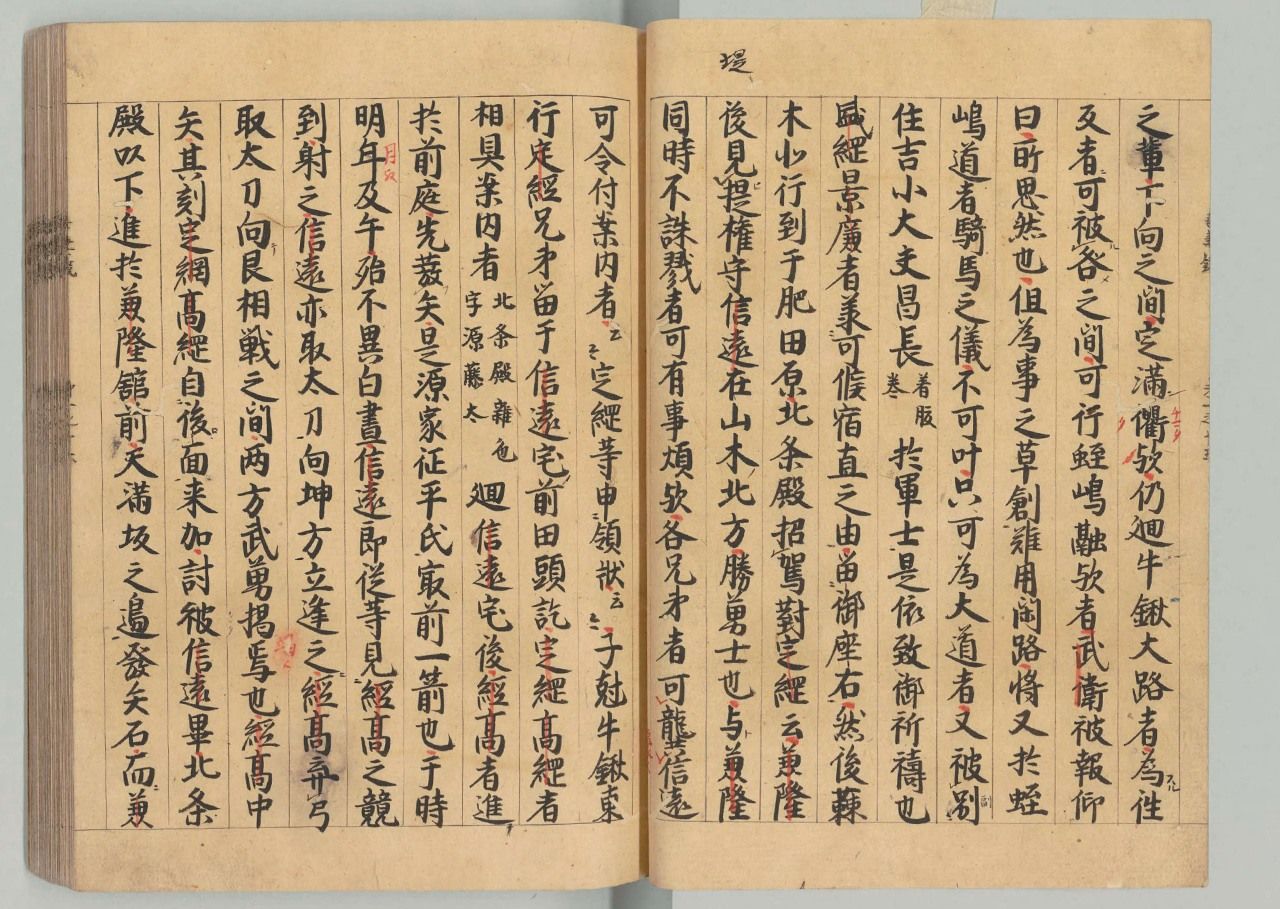

The Genpei War began when Sasaki Tsunetaka, of the Minamoto clan, attacked Taira vassal Yamaki Kanetaka with an incendiary arrow in the Izu area. Azuma kagami (above), the medieval chronicle of events of the Kamakura Shogunate, describes the incident, which took place on August 17, 1180, as “the first arrow in Minamoto’s subjugation of the Taira.” (Courtesy the National Archives of Japan)

When we visited the museum, preparations were well underway for the second part of the exhibition series, “The era of the Kamakura samurai,” set to open on April 9, which shifts the focus from Yoritomo and his army to the “13 lords” featured in the NHK show. It is a collaboration with the Kamakura Kokuhōkan Museum, located within Kamakura’s famous shrine, Tsurugaoka Hachimangū. The Kokuhōkan display spotlights martial history, while the Kamakura Museum of History and Culture focuses on the administrative duties of the samurai.

Under Yoritomo, the warriors of the eastern provinces established the shogunate through military strength, but they maintained it through their administrative prowess, requiring proficiency in poetry, music, and literary arts. Although waka poetry is commonly perceived as an aristocratic pursuit, Ōsawa explains that it was an important tool for samurai in negotiations with the imperial court, to avoid being considered uncultured.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The main entrance to the Kamakura Museum of History and Culture. © Mochida Jōji.)

Kamakura Museum of History and Culture

- Access: A 10-minute walk from JR Kamakura Station, west exit

- Hours: 10:00 am to 4:00 pm (Closed Sundays and national holidays)

- Admission: ¥400; ¥150 for students up through ninth grade

- Tel.: 0467-73-8545

Hōjō Exhibition

- Part 1: “From Izu to Kamakura” (Jan. 4–Mar. 26)

- Part 2: “The era of the Kamakura samurai” (Apr. 9–Jun. 11)

- Part 3: “The era of Hōjō Yoshitoki” (dates to be confirmed)

- Part 4: “The children of Hōjō Yoshitoki” (dates to be confirmed)