Historical Landmarks of the Kamakura Lords

Yōfukuji: Computer Graphics Bring a Lost Kamakura Temple Back to Life

History Travel- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

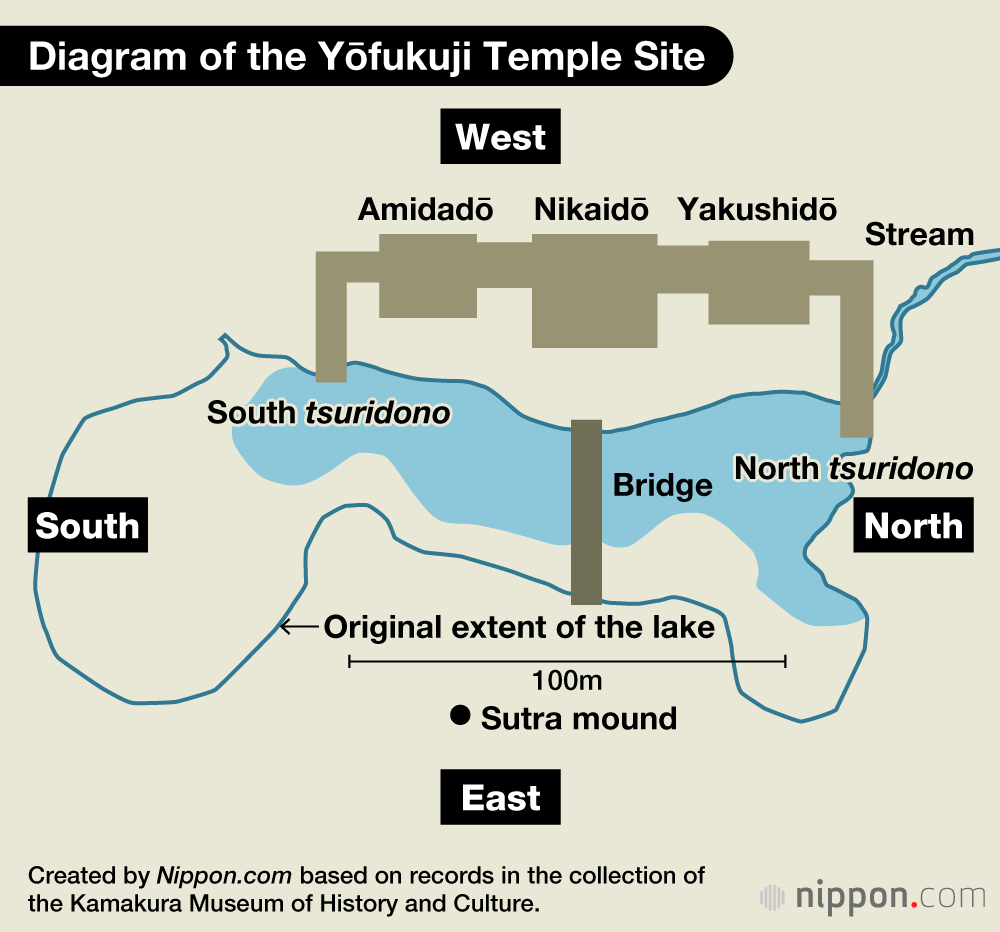

Three Halls and a Lake

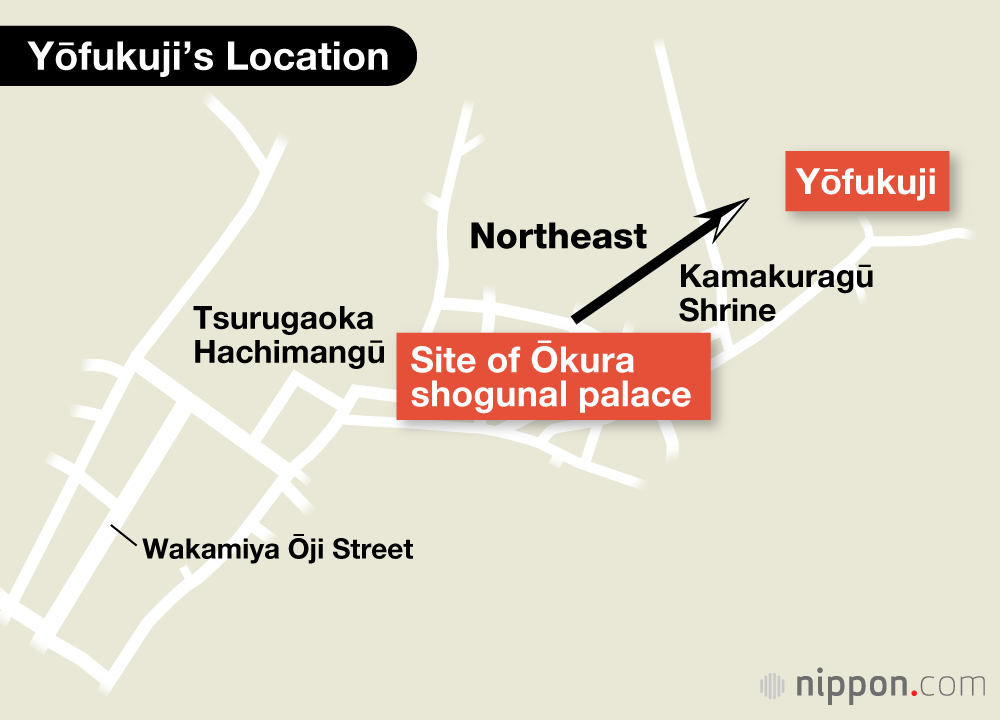

Ten minutes northeast of Kamakura Station is Kamakura-gū, a Shintō Shrine. A five-minute walk from the shrine brings you to an expansive, well-maintained grassy park covering some 16,000 square meters. The park, which opened in July 2017, marks the site of what was once the temple Yōfukuji. Looking down from a small hill across the park, it is easy to make out the layout of the sacred precincts: three square raised foundation platforms (known as kidan) where the main halls once stood, fronting a gourd-shaped pond. Even today, the size of the platforms still gives an impressive sense of the splendor of the temple that once stood on the site.

The gourd-shaped pond is more than 100 meters wide. (© Mochida Jōji)

The raised platform foundations of the Nikaidō, or Two-Story Hall. (© Mochida Jōji)

A transept juts out from the remains of the foundations on the south side and touches the edge of the pond. A sign describes it as a tsuridono, a type of small lakeside pavilion whose name literally means “fishing palace.” Did people used to cast a line from here and fish in the lake? On the north side of the foundations is a small stream (yarimizu), small pebbles arranged as if to bring out the soothing burble of the water running over stone. It is the kind of design that might have appealed to Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147–99), who was born in Kyoto and never lost his affection for the elegance and refinement of the old capital.

A tsuridono pavilion once jutted out from the Amida Hall (foundation at left); a small stream runs on the north side of the site. (© Mochida Jōji)

Today, the temple site can be visited as a pleasant park. But for centuries after the buildings were destroyed in a fire, Yōfukuji only existed in historical records. The temple was completed in 1194, just two years after Yoritomo was appointed shōgun. Why did he have this temple built, and why here? What form did the building take? The answers to these questions can shed important light on Yoritomo’s life and provide important clues into the character and worldview of this important historical figure.

A view across the site of the Yōfukuji historical park. The foundations on the right mark the site of the Yakushidō (Yakushi Hall). On the left are the remains of the Nikaidō. (© Mochida Jōji)

This computer-generated image shows the site as it might originally have looked from almost the same angle as the photo above. (Computer graphics by Nagasawa and Inoue Research Lab, Shōnan Institute of Technology)

A Surviving Placename Provides a Vital Clue

Descriptions of Yōfukuji in the Azuma kagami contain frequent mentions of a “two-storied hall” and the “three halls” of the temple complex.

Based on only these slivers of historical evidence, in 1933 a local archeologist decided to explore a local area whose name, Nikaidō, suggested that it might correspond to the site of the lost temple. He speculated that an area of nearby rice paddies might once have been the location of the lake known to have stood on the temple grounds, and preliminary explorations uncovered steppingstones originally from the temple grounds. Surveys started again after the war, and a full-fledged archeological dig got underway from 1983.

That same year, archeologists discovered the remains of a large, square hall, 20 meters on a side. “The following year, the team started digging to the south of the large hall, and found the remains of a somewhat smaller hall,” explains Fukuda Makoto, member of the Cultural Properties division of the Kamakura City Education Committee and one of the archeologists working on research at the site. “On the hunch that this might have been one of a pair of similar structures that originally stood on either side of the large main hall, the team went around and started digging on the north side. And sure enough, they found another smaller hall built on a similar design on the north side of the main building.”

Archeological features at the Yakushidō site. (Courtesy of the Kamakura Board of Education)

The archeologists had unearthed evidence that matched the historical records: “three halls,” the Yakushidō and Amidadō (Amida Hall) centered on the Nikaidō, a central main temple hall.

It became clear that the two smaller buildings on either side of the central Nikaidō were the Amidadō on the south side and the Yakushidō on the north. The Buddhist images that must once have been worshiped here were destroyed in the fire along with the buildings that housed them. This style of temple architecture, in which a series of temple buildings stand as a “set” on the banks of an ornamental water feature is known as the “Pure Land” style, designed to symbolize the “Pure Land” of the Amida Buddha who promises rebirth in his Western Paradise to all living beings who call his name.

The hand of a Buddhist image excavated on the site, at left, and a gargoyle (onigawara) from the roof of one of the temple buildings. (Courtesy of the Kamakura Board of Education)

A little behind Yōfukuji on the western side is a small hill. When the setting sun sank below the ridge of the slope, it would apparently cast a halo of light over the roof of the temple from behind. The whole structure was designed to evoke Amida’s paradise.

Yoritomo’s Fear of Ghostly Revenge

But why was Yoritomo so eager to recreate the Western Paradise on earth in this temple? At least part of the reason seems to have been anxiety about his two main rivals for power in the years after he cemented his authority and established his shogunal government in Kamakura. The first was his own younger brother Yoshitsune, who had aroused Yoritomo’s suspicions while working to wipe out the last traces of resistance from the rival Taira clan following their 1185 defeat at Dannoura. The second was the Northern Fujiwara clan, who had not only shielded Yoshitsune in his flight from his brother but posed a potential threat as a rival power base in the northeastern hinterland of the country beyond Kamakura. Yoritomo was determined to wipe out both these potential rivals.

Fukuda says, “There’s no doubt that Yoritomo was worried about revenge from the angry spirits of Yoshitsune and the Northern Fujiwara. The ushi-tora, or ox-tiger, direction to the northeast was known as the ‘Demon Gate,’ and was believed to be the direction from which demons and malign spirits came in and out. By constructing Yōfukuji to the northeast of the shōgun’s palace, the idea was keep evil spirits far from Yoritomo and his retinue.” And perhaps the Pure Land style of architecture was intended to mollify the spirits of Yoshitsune and Yasuhira, the last lord of the Northern Fujiwara: “look, you’re in this beautiful, serene paradise. So stay here and don’t come and bother me in my palace!”

A copper sutra container excavated from the sutra mound. These containers were used to preserve Buddhist sutras, but apparently no sutra was found inside this container, perhaps because it had already eroded over the centuries. (Courtesy of the Kamakura Board of Education)

Computer Graphics Bring a Lost Temple Back to Life

The original temple would have been made almost entirely of wood. Since it was destroyed in the fire it is hard to imagine what the site originally looked like in all its splendor. Recently, though, a team led by Nagasawa Kaya and Inoue Michiya at the Shōnan Institute of Technology has succeeded in bringing the temple back to life with the help of computer graphics.

A computer-generated simulation of the view from the south side of the Yōfukuji site. (Courtesy of Nagasawa and Inoue Research Lab, Shōnan Institute of Technology)

In creating the computer images that would bring the temple back to virtual life, the team had to rely on the few scraps of evidence that remained. For example, buildings of the time did not have gutters on their roofs. Instead, rain would drip off the roof into a ground-level gutter below the eaves. Since the position of this gutter can still be discerned in the foundations, this gave the team a vital clue as to the size and extent of the original roofs. Some shards of wood found in the lake are believed to have once formed part of the framework of the bridge. The curvature of this wood was used to re-create the image of an arched bridge spanning the lake in front of the main temple structures.

Rain would once have fallen into the space now filled with pebbles. (© Mochida Jōji)

Visitors can use a smartphone to view the CG reconstruction of the temple on site. (© Mochida Jōji)

The Phoenix Hall at the Byōdōin in Uji, another famous example of Pure Land temple architecture. (© Jiji)

Professor Nagasawa does not hide his surprise at what the simulation has revealed: “Without extremely precise technology, it would have been impossible to construct a building like this,” he says. The corridors around the main hall extend in a perfectly straight line for 130 meters, while the axis line of the bridge that once spanned the lake from the center of the group of temple buildings is perfectly aligned with the main Nikaidō hall.

Professor Nagasawa Kaya (left) and Fukuda Makoto of the Kamakura municipal government’s cultural properties division. The fragment of wood in Fukuda’s hands is thought to be part of a Buddhist image. (© Mochida Jōji)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The remains of Yōfukuji as viewed from a hill on the south side of the site. The raised foundations of the three main structures can still be seen clearly: from the front, the Amidadō, Nikaidō, and Yakushidō. The group of temple buildings would originally have faced an ornamental lake. Photo courtesy of the Kamakura Museum of History and Culture.)

Access

Yōfukuji-ato (Historical Park): From Kamakura Station take a bus for Daitō-no-Miya and get off at the final stop. The site is a five-minute walk to the northeast. Entrance to the site is free.