Japanese Traditional Annual Events

Nagatsuki: Chrysanthemum Festival, Viewing the Waxing Moon, and Other Traditional Events in September

Culture Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Celebration of Chrysanthemums

September marks the celebration of chōyō, also known as the Chrysanthemum Festival, the last of the five seasonal festivals (gosekku). Traditionally falling on the ninth day of the ninth month of the lunar calendar, today it is observed on September 9.

As with the other sekku, which have their roots in Chinese philosophy, the significance of chōyō lies in the power of odd numbers, which represent the positive yang in the ancient yin-yang cosmology system. The pairing of odd numerals in the dates of sekku was considered auspicious and was believed to have the capacity to ward off maleficent spirits. The number nine, as the highest of the yang digits, was particularly powerful, and special ceremonies meant to dissipate some of the force became part of the early rituals associated with chōyō.

The earliest reference to the Chrysanthemum Festival in Japan comes from the eighth century history Nihon shoki, which mentions a banquet held during the reign of Emperor Tenmu in 685. The practice was short-lived, though, as Tenmu’s death on chōyō the following year made observing the anniversary of the emperor’s demise a priority. More than a century later, in 807, Emperor Heizei issued an imperial decree reviving the festival, and records show that by 831 chōyō no sekku had reclaimed its place on the calendar of annual events.

The first celebrants of chōyō marked the day by drinking sake containing chrysanthemum petals in the belief that the flowers had the ability to boost longevity, a practice that the aristocracy of the Heian period (794–1185) heartily adopted as part of their celebrations.

By the Edo period (1603–1868), the cosmological aspects of chōyō and focus on health and longevity had faded, and the day was primarily devoted to the adoration of chrysanthemums. The Tokugawa regime’s institution of the observance of the gosekku helped popularize the festival among the warrior class and society more broadly.

Chrysanthemum Viewing, from Yōshū Chikanobu’s series Chiyoda Inner Palace, depicts courtesans from the shōgun’s “inner chambers” enjoying an afternoon of flower viewing inside the confines of Edo Castle. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Interest in the cultivation of the flowers exploded during the Edo period. A wide array of new varieties of chrysanthemums were developed starting in the early eighteenth century, and several popular gardening manuals appeared that described cultivation techniques and methods for creating elaborate displays, which became all the rage. As the popularity of chrysanthemums grew, competitive flower shows were held in which enthusiasts would show off their gardening skills. The nineteenth century saw the appearance of intricate displays of chrysanthemums in the shapes of boats, doll-like figures, and other objects, a trend led by such famed gardeners as Imaemon, who created an intricate treelike piece consisting of hundreds of flowers.

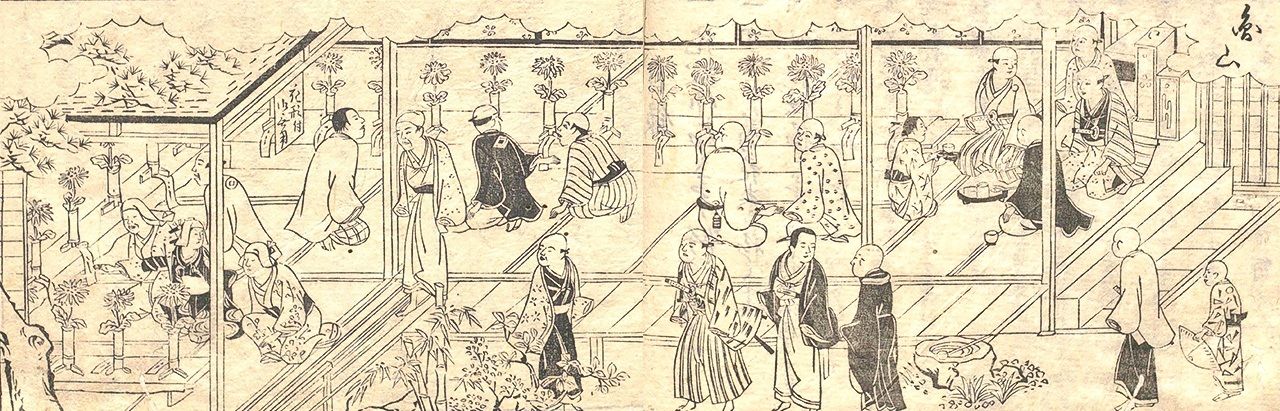

People enjoy a flower exhibit in a print from Collection of Cultivated Chrysanthemum Displays, published in 1715. (Courtesy National Institute of Japanese Literature)

Enthusiasts flock to see the tree-like display of chrysanthemums by famed gardener Imaemon, as depicted in the print Chrysanthemum Viewing: 100 Varieties Grafted on a Single Plant by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Along with chrysanthemums, chōyō traditionally marked the time for people to exchange their light, summer garments for heavier items as the weather cooled. Today the custom is observed at the start of October, but at the time it was thought appropriate for the fashionable denizens of Edo and other cities to finish their seasonal change of wardrobe by the end of the Chrysanthemum Festival.

Sweets and the Waxing Moon

Autumn is traditionally a time for moon viewing. The appearance of the full moon on the fifteenth night (jūgoya) was particularly celebrated, but the waxing moon that appeared on the thirteenth night, or jūsanya, was also admired.

Jūsanya no tsuki: the moon appears almost full on the thirteenth night of the lunar calendar. (© Pixta)

The nearly full moon corresponded closely with the chestnut harvest and was also known as kurimeigetsu, or “chestnut moon.” As with other moon-viewing events, it was customary to admire the heavenly body along with refreshments of rice dumplings. A woodblock print by Meiji-era artist Utagawa Hiroshige IV shows the confection covered in kinako, sweetened soybean powder, suggesting a different culinary custom from dumplings slathered with bean paste typical of the full moon on the fifteenth.

Residents of Edo were a superstitious lot, and skipping either jūsanya or jūgoya moon viewing was deemed unlucky, a taboo known as katamitsuki.

Kanda Festival

In Edo, a highlight of the ninth month was the Kanda Matsuri, the main celebration of the Kanda Myōjin Shrine. Today held in mid-May in odd-numbered years, it used to take place on the fifteenth day of the ninth month and was one of the capital’s three great festivals. Another important shrine, the Shiba Daijingū, also held its festival around the same period, which ran from the eleventh to twenty-first days of the month.

Edofunai ehon fūzoku ōrai (Picture Book of Edo Customs and Manners) by Utagawa Hiroshige IV depicts celebrants outside Shiba Daijingū, which was closely associated with the Ise Shrine. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

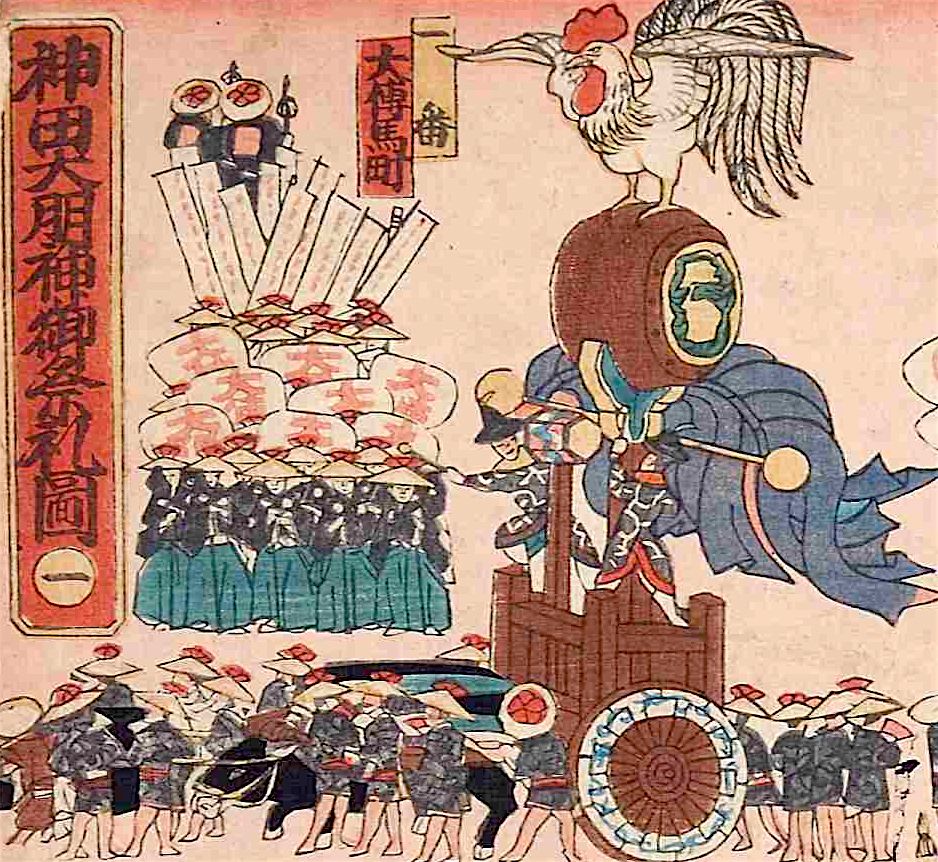

The Kanda Matsuri, held once every two years, enjoyed the special patronage of the Tokugawa regime. It featured a long parade of floats (dashi), portable shrines (mikoshi), and other structures representing some 60 neighborhoods that wound its way through the streets and even into the confines of Edo Castle, where the shōgun was known to view the spectacle. The length of the parade was legendary, with an 1854 work by ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Yoshitsuna showing it stretching from the castle gate at Tokiwa Bridge to Shōhei-zaka at the base of Yushima Seidō, a distance of some two and a half kilometers. (By comparison, the current parade is only around 300 meters in length.)

A mythical kankodori (drum-bird) rides atop the first of the parade’s 36 floats, as depicted in a print by Utagawa Kunisato. (Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room)

While famed for its length, the parade, as a government-sanctioned event, was relatively subdued compared to more plebeian celebrations, with participants keeping festivities from becoming overly raucous. The shōgun provided funding for the Kanda Matsuri but was also known to cancel the event during times of misfortune.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A print by Utagawa Yoshifuji depicting parade floats during the Kanda Matsuri. Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room.)