Japan’s Ig Nobel Prize Winners

Changing the Future of Food with “Electric Salt”: Ig Nobel for “Augmented Gustation Using Electricity”

Science Education Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Making Use of “Electric Taste”

New products that aim to bring flavor to bland low-sodium cooking are on their way. Under the brand name Erekisoruto, a coinage from the Japanese pronunciations of “electric” and “salt,” they use a harmless electric current to strengthen the perception of saltiness in food. The hope is that they can support reduced sodium in food and so aid in the prevention of lifestyle diseases linked to excess salt intake.

The technological basis for Erekisoruto is a research paper that fell into the spotlight in September 2023 with its selection for the Ig Nobel Nutrition Prize.

Miyashita Hōmei, a professor at Meiji University and member of the research team, said “Our research started in 2010. I was honestly shocked to hear that it had been assessed and won the award after 13 years.” He heard the news from his research partner, Project Associate Professor Nakamura Hiromi of the University of Tokyo.

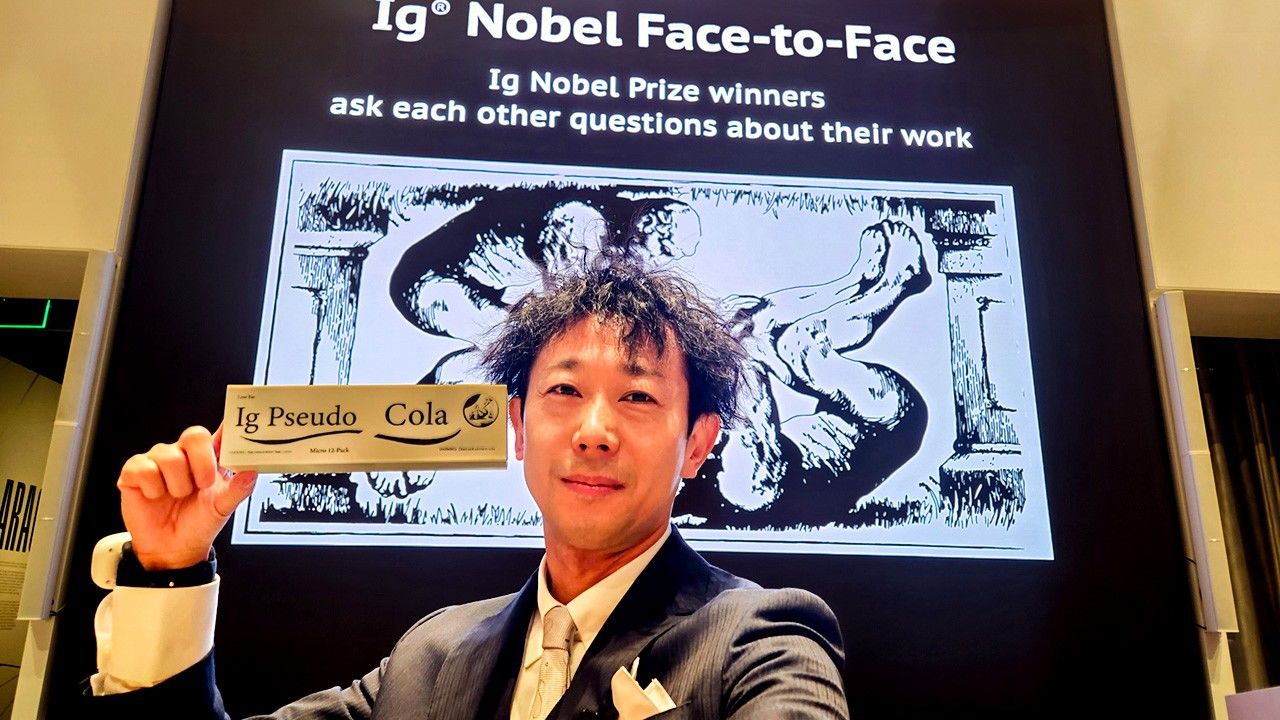

Miyashita attended the Ig Nobel Ceremony at the MIT Museum in September. He commented, “I was worried that the other award winners might be difficult eccentrics, but everyone was serious about their research. I was impressed at what good communicators they all were.” (Courtesy Miyashita Hōmei)

Nakamura had this to say about the motivation for the research:

“At the time, I was a student in Dr. Miyashita’s lab, and I was interested in something called ‘tongue interfaces’ that allowed interaction with electronic devices using the tongue. We were making progress developing systems to allow people with manual dexterity issues to operate devices using their tongues. In connection with that, I was talking to Dr. Miyashita about using taste as feedback in confirming input accuracy and hit on the idea of using ‘electric taste’ there.”

Nakamura Hiromi played a part in the development of “electric salt.” (© Nakamura Hiromi)

Humans perceive taste using cells called taste receptors which detect taste-bearing particles as sweet, sour, salty etc., then transmit those stimuli to the brain as electronic signals. However, that reaction is not limited to food. Electricity flowing to the tongue can also cause taste perception.

This electric taste has long been a target of study, primarily in medicine, such as in a test used to determine the severity of taste disorders. Miyashita and Nakamura, on the other hand, are continuing their own research in hopes of creating new taste experiences through electric gustation.

“As we repeated our tests, we found that we could quickly alter the flavor of food using electric stimuli. We thought that, rather than limiting ourselves to tongue feedback, researching the changes in food taste itself would be a better way to bring happiness to more people. So, we changed direction,” says Nakamura.

They first announced their research in 2010, the year it began, with a paper that proposed using straws and chopsticks with weak electric currents to change taste perceptions. That is what won them the Ig Nobel.

The pair were the first to propose a system that sends electrical stimulation to the tongue through food rather than touching electrodes directly to the tongue.

“We later found that using the food as a medium resulted in electrical stimulation effects that spread beyond the taste receptors. The positive and negative ions moved within the food and caused more complex phenomena. When we realized that, we thought it could lead to a bigger invention that could actually control taste and change the future of food,” said Miyashita.

Practical Trials of Flavor-Boosting “Electric Salt”

Miyashita carefully nurtured the seed of that bigger invention, and in 2019, began joint study on electric taste with Kirin Holdings.

It is commonly held that the Japanese diet is extremely high in sodium. Although more people are becoming health conscious and attempting to reduce salt in recent years, a great many feel dissatisfied with the resulting food. Kirin and Miyashita are working together to use electric taste to offer more enjoyable low-sodium diets.

The research proceeded smoothly and, in 2022, they developed technology that could increase the perception of saltiness in low-sodium food by about 50%. Erekisoruto products incorporate this technology.

An Erekisoruto bowl and spoon. (© Kirin Holdings)

For example, one could eat low-sodium ramen noodles from the bowl product. Turn on the switch and, like magic, the dissatisfying ramen suddenly tastes as salty and delicious as normal.

The fundamental principle explaining that change is, when an electric current runs through the dish, the sodium ions in the food collect on the tongue, causing a stronger salty taste. The sodium ions in food, which are the source of food’s salty flavor, have a positive charge and so can be moved by electric current.

“You don’t need to add salt—just add electricity. The flavor is almost the same as if you had added salt. In fact, I think there is greater umami and that makes it even more delicious,” says Miyashita.

Inspired by an Elementary School Experiment

Common sense tells us one has to ingest food to appreciate its flavor, but using Erekisoruto, one can enjoy a salty flavor without ingesting much salt. In other words, it separates flavor from ingestion. The root of that idea was born in an experience Miyashita had in elementary school.

“During class I pressed on my eyelids, and I noticed that I could see black spots on the backs of my eyelids. I thought it might be interesting if I could make letters instead of just spots, so I experimented with pressing on my eyelids in different ways.”

The phenomenon occurs when pressure on the eyeball stimulates visual receptors on the retina, which in turn influences the visual field. The young Miyashita wondered about the reason and continued pondering it, and eventually came up with a fascinating idea.

“The experiment made me wonder, if all the light vanished from the world, could I make light? Even if we could not generate the phenomenon of light, could we generate the experience of light by stimulating the receptors that perceive it?”

In other words, Miyashita noticed the disconnect between the subjective perceptions of sight, taste, and smell, created by receptors and brain processing, and the objective physical world of matter and energy. This childhood realization later led him to research electric taste and taste media.

Expanding the World of Flavor

Taste media refers to using information technology to convert taste into data and deliver it to people, similar to viewing media such as television that delivers images. Electric taste and Erekisoruto are examples of such, and Miyashita has been deeply involved in research in this field.

Other results of his work include the successful development of TTTV, a device that can change food flavors as specified. The latest device, released in 2023, can change the flavor of white wine to red, give cheap chocolate a luxurious taste, or even make milk taste like crab-cream croquettes so that people with shellfish allergies can enjoy the taste of crab.

In 2016, Nakamura announced the Electric Taste Fork, which allows people to sense saltiness through electric taste. An event with a “full course of salt-free cuisine” eaten with the fork won the Excellence Award at the Japan Media Arts Festival that same year. She has since continued to work on developing transcutaneous electrical stimulation, building connections to expanding the possibilities of electric taste apart from Miyashita.

In talking about the future of her research, Nakamura says,

“Electric taste can help those trying to reduce salt or who have other dietary restrictions. I think it also has elements of entertainment which can create unexplored taste experiences. Now that the Ig Nobel prize has made more people aware of electric taste, I hope we can convey its appeal more effectively to make it even more common.”

Miyashita also shared his dreams for the future.

“If we were able to recreate all kinds of flavors using a computer, we could taste whatever we wanted, all we wanted, without worrying about our bodies. We could also reduce food waste by, for example, making overripe tomatoes taste like perfectly fresh ones, so we would only worry about expiration dates, rather than best-by dates. My goals are still expanding, so after the encouragement of this award I’m going to work on developing taste media every day.”

The TTTV3 taste adjustment device from Miyashita Laboratory (left), the bottle-top version TTTVin (right), and the prototype spoon and fork flavor adjustment devices (foreground). (Courtesy Miyashita Hōmei)

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview and text by Sugihara Yuka and Power News. Banner photo: Miyashita Hōmei receiving the Ig Nobel Nutrition Prize at the November 2023 ceremony at the MIT Museum. Courtesy Miyashita Hōmei.)