Remembering the Heiwa Reservoir Flood and Its 114 Victims

Disaster History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A National Plan Leading to Tragedy

The Heiwa Reservoir Flood Monument stands at the side of a road some four kilometers south of JR Kameoka Station in Kyoto Prefecture, just past a residential neighborhood. It is near the landing for the Hozugawa boat rides, which explore the narrow, boulder-strewn river valley. The city built the monument in September 2011. At its dedication, the mayor said, “The Heiwa reservoir flood is a disaster that the city of Kameoka must never forget. Those of us living here now have been given the duty of passing on the lessons of that calamity.”

The monument stands in memory of the 114 people who died and the 238 who were injured when the Heiwa Reservoir Dam, which stood upstream on the Toshitani River, a tributary of the Hozu, burst on July 11, 1951, after a sudden heavy rain. In the disaster, 268 homes were washed away or destroyed, another 152 were flooded above the floor, and 497 flooded to the foundations. The Kasebara area of former Shino village was particularly hard hit, with 75 dead. The former Kameoka township lost 21 people. No one could have dreamed that a reservoir pond could cause such enormous damage.

The dam that broke was an earthen embankment, or earthfill dam, on a branch of the Toshitani River. The former Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry planned five model dams for flood control and irrigation purposes and invited Kameoka town to join the program. The dam was 19.6 meters tall and 82.5 meters long and was built to hold 220,000 tons of water.

It was completed in September 1949 but did not last two years before bursting. Nakao Yūzō, founding member of the local Heiwa Reservoir Flood Memorial Association, remembers the weather at the time. The day before the collapse, July 10, was a sunny summer day. However, a low-pressure system collided with the seasonal rain front over the southern Korean peninsula and pushed rain clouds toward western Japan. In the early hours of July 11, the area around Kameoka was inundated with heavy rain. The Kyoto Weather Measurement Station at the time measured some 66 millimeters per hour of precipitation. Nakao, who was a second-year student at Anjō Elementary school, remembers, “The rain and thunder were terrifying.”

Reasons Left in the Dark

According to the monument, the levee along the right side of the Toshitani river broke around 9:30 am on July 11, and water began pouring toward Kasebara. About 10 minutes later, the water pressure exceeded the endurance of the main dam on the Toshitani River and it burst. Roughly 90 Olympic-sized swimming pools worth of water rushed in a black mass downstream and overwhelmed the village of Kasebara in an instant. That was 20 minutes after the rupture.

The village of Kasebara consumed by muddy water. (Courtesy the Heiwa Reservoir Flood Memorial Association)

The breaking of the Heiwa Reservoir Dam shocked all of Japan. It had, after all, been a model government project. A MAF survey team traveled to the flood zone the day after the disaster, and two weeks later a construction committee from the National Diet joined the survey. The reason for the collapse became a topic of debate in the Diet, but no conclusion was reached. A lawsuit by the surviving victims was settled without clarifying the reasons. To this day, no one knows if it was simply due to an unprecedented and unpredicted amount of rainfall or a flaw in the design.

Nakao, though, has reviewed various records in his investigation work with the Memorial Association, found a mention of the incident in an article called “Dam Accidents around the World” (Japan Dam Association, 1966) which described the bursting of the Heiwa dam as due to “improper management.” He says, “It seems reasonable to think there was a problem with project management, like that the dam design standards of the day were insufficient or there was some problem with the civil engineering techniques. But it is just as important that this was seen as such a serious dam accident. The questions of safety that the Heiwa Reservoir Dam collapse posed live on today in this disaster-prone archipelago.”

A Disaster Beyond Words

The Heiwa dam collapse was a disaster beyond words. Although there have been memorials and disaster monuments in the Kasebara area and along the Toshitani riverside in old Kamiyata, Kameoka, it has taken 60 years for the city to erect one that commemorates the whole of the disaster.

The disaster seems to have remained in the shadows due to a history of split local opinion over the dam invitation. The old township of Kameoka was in favor of the original construction project due to its need for stable irrigation, but the downstream residents of Kasebara in Shino opposed it out of fears it would interfere with their water supply. It is not difficult to see why the people of Kasebara might hold ill feelings toward Kameoka, which pushed through the objections to accept the project. Kameoka became a city in full after 15 area municipalities merged in 1955, but the village of Shino refused to join the city until 1959.

Against that backdrop, the story of the disaster became one ignored in Kameoka. A half-century after the flood, in 2001, Nakao says that he felt a sense of crisis. “If things went on like that, everyone would forget the people who lost their lives in the Heiwa reservoir flood, and even the fact of the flood itself.” The next year, he helped found the precursor to the modern Memorial Association, the Special Committee for Collecting and Compiling Records on the Kasebara District Heiwa Reservoir Flood. They began with local interviews. Many of the flood survivors were elderly, so it was a race against time. The materials the committee gathered little by little were compiled in 2009 into the volume Telling the Story of the Heiwa Reservoir Flood: Requiem for the Kasebara 75. The work was awarded the third Annual Hometown Private Publication Prize by the National Newspaper Publishers Council.

Nakao discusses displays of photographs and other materials from the flood at the Kasebara Community Hall. (© Abe Haruki)

From there, work expanded to include disaster prevention classes at elementary and junior high schools, lectures to politicians and local governments, and public exhibitions. This led to the city’s general monument. Fourth graders at the local Shōtoku Elementary School created a picture-story show about the flood after they listened to such a lecture, and they continue to share it within the school.

Dams Continue to Break across Western Japan

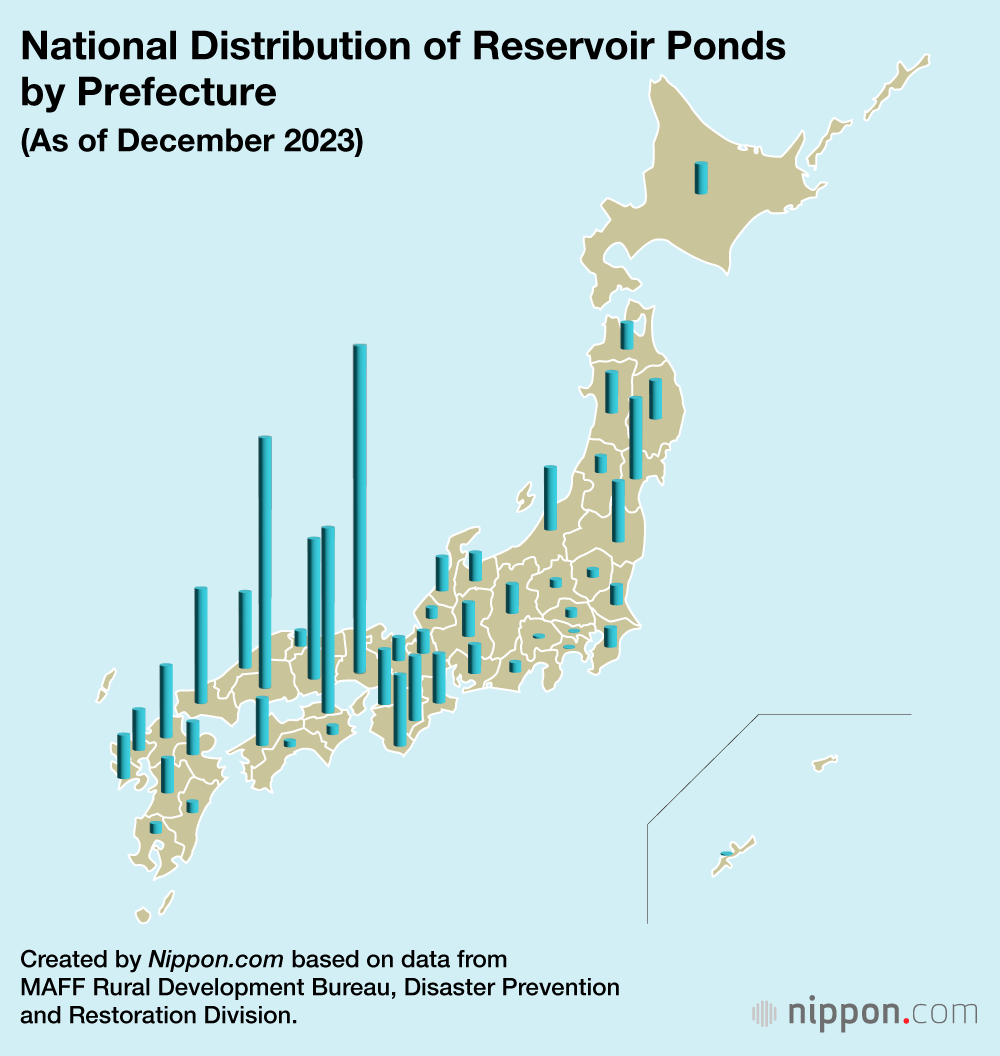

An investigation by the government’s Disaster Prevention and Restoration Division showed that as of December 2023, there were 151,191 reservoir ponds across Japan, with about half of those in western Japan. They have become a fixture for local communities to ensure irrigation water supplies. Many have also grown to become beloved parts of the local scenery. However, some 70% predate the Meiji Restoration of 1868, and they are deteriorating even as local rainfall is increasing. More dams are in danger of breaking.

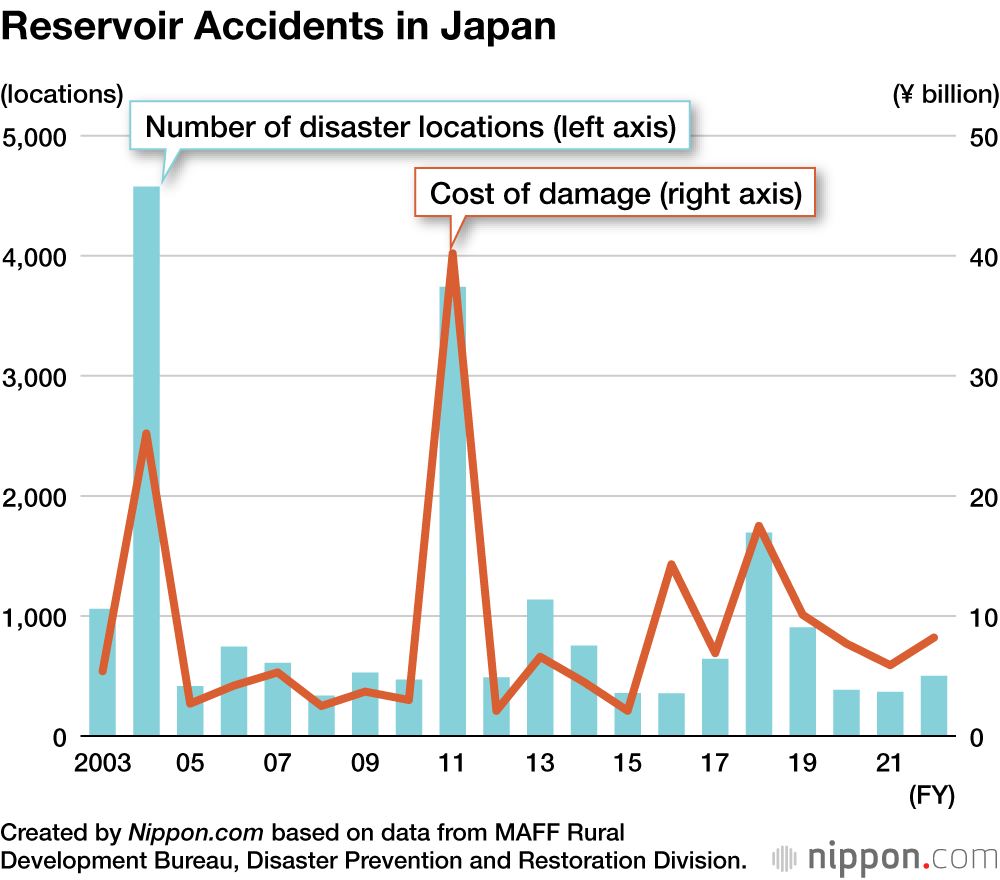

The ministry reports that there were 7,098 reservoir incidents in the years 2013 to 2022. Going back even further, in 2004, the Niigata Chūetsu Earthquake and the 10 typhoons (the Japanese definition includes tropical storms) that made landfall caused over 4,500 incidents, and in 2011 the impacts of the Great East Japan Earthquake led to nearly 4,000.

In fact, the Great East Japan Earthquake caused a break in the Fujinuma Dam in Sukagawa, Fukushima Prefecture. The resulting flood killed seven people and one more disappeared without a trace. The Fujinuma Dam was the same earthfill type as the Heiwa dam, and the flood was similar. Kameoka’s Memorial Association donated disaster relief funds and joined with the Committee to Erect a Memorial to the Fujinuma Dam Burst to help preserve the memory of the disaster for the future.

Thousands of Locations Need Repairs

The national government is aware of the problem, and in 2019 implemented the Act on Reservoir Preservation. It required municipal mayors to share information about reservoir risks to residents by creating hazard maps, as well as other measures. The next year, it enacted the Special Measure on Reservoir Construction. That established a system whereby prefectural governors could identify High-Risk Agriculture Reservoirs, such as those near residential areas with serious damage potential, for focused disaster mitigation construction and planning. As of the end of fiscal 2023, a total of 53,399 target locations have been identified.

Following the implementation of those two laws, the Administrative Evaluation Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications conducted a survey on disaster prevention and mitigation measures targeted reservoirs in 66 municipalities in 11 prefectures from October 2022 to June 2024. The survey report published on June 21 makes the delay in construction immediately apparent.

Those reservoirs identified as high risk and in need of construction as per the special measure numbered 10,089 as of the end of fiscal 2022. However, only 1,024, or some 10%, had started construction at that point. That measure expires in fiscal 2030, so any related construction should be started by then. However, only 2,380 or 23.6% of the target locations are expected to meet that goal. Hazard map creation is also lagging, with only about half of the 8,543 target locations, or 4,229, completed.

Real-Time Risk Assessment

What do the experts have to say about this? Ibaraki University Professor Emeritus Mōri Yoshiyuki, an expert in agricultural civil engineering, says, “It is a positive thing that there is a system for prefectural governors to plan disaster mitigation measures for reservoirs that pose a predictable risk.” He also praises the survey report, saying, “It is quite meaningful in that it offers a concrete action manual for local governments, presenting a fundamental concept and operational direction for disaster mitigation administration.” He also says that it should be the basis for future seamless sharing of roles between the national administration, local governments, and related organizations.

With the coming of the Reiwa era in 2019, we saw a concerted effort to make up for the lag in reservoir disaster mitigation. One aid group that has appeared to help reduce this risk is the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO). From 2018 this research agency initiated the Reservations Disaster Mitigation Support System, which went into full operation in 2020. It uses AI to estimate and display in real time the level of risk of reservoir dam burst and offers local governments information to prevent damage.

Professor Mōri calls the system a “groundbreaking way to actually avoid risks.” NARO spent over 15 years working on research and technical development for reservoir disaster prevention, and its ability to gather and share disaster information is one result. Hopes for the new system’s future aid are growing.

At the same time, local efforts like those of the Heiwa Reservoir Flood Memorial Association are also essential. Professor Mōri says, “Telling the story helps nurture greater resilience to disaster in local areas. I hope that word spreads nationwide.”

(Originally published in Japanese on November 27, 2024. Banner photo: the Heiwa Reservoir Flood Monument. © Abe Haruki.)