Vanishing Act: The Kishida Administration’s Disappearing Human Rights Adviser

Politics Society Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Backtracking on a Bold Human Rights Move

In September 2021, during his campaigning for the presidency of the Liberal Democratic Party, Kishida Fumio pledged that he would take a firm stand on human rights issues if he were to win and serve as prime minister. Once he secured that post, he tapped former Defense Minister Nakatani Gen to serve in a new cabinet post, special advisor to the prime minister on human rights.

There are a range of takes on Kishida’s performance as prime minister over his three years in office, but in the end, the way that this new human-rights-related post played out will remain a blot on Japan’s international image.

Originally held up by Kishida as a signature position in his administration, the post of human rights adviser would disappear just two years later, when he reshuffled his cabinet in September 2023. In its place appeared a new position, an adviser specializing in wage and employment issues. Kishida’s high-profile appointment of Yata Wakako—a former member of the House of Councillors who served as vice-president of the Democratic Party for the People and a member of the Panasonic labor union—to this post filled the quota of five special advisers to the premier, and Nakatani saw his position evaporate.

When asked by Jiji Press about his accomplishments during his two years in the post, Nakatani pointed to two themes he had pursued in a newly formed interministerial conference: the formulation of an action plan to prevent forced labor and other corporate infringements of human rights, and consideration of domestic systems to improve acceptance of refugees.

Indeed, in some areas progress was made, with Nakatani and the cabinet taking the lead on these issues to prompt action in the Diet. But Kishida’s 2023 decision to axe the advisory post sent the wrong signal to the global community, and in the sum, the negative impact of this move far outweighed any positive accomplishments during those first two years.

The Rights Gap Between Japan and the Rest of the World

In my journalistic coverage of international organizations over the years, the area of human rights is where I have felt one of the largest gaps between Japan’s views and globally accepted standards. During the 1990s, when I covered the European Headquarters of the United Nations, Japan came in for annual criticism of its daiyō kangoku, or “substitute imprisonment,” system that can keep detainees locked up in police custody for up to 20 days per charge, with no chance of bail and little access to legal counsel.

I must admit, to my shame, that when I was a young reporter working the crime beat, I never had a doubtful thought about the “substitute imprisonment” system. It was only when I first started covering the discussions of the UN Human Rights Committee that I realized this use of police cells in place of appropriately appointed detention centers was a way for the police to subject detainees to long hours of interrogation, producing fertile ground for illegally coerced confessions. At last it was clear to me that the standard Japanese way of doing things had little in common with internationally accepted norms.

One international standard in the human rights area is a domestic organ to handle rights issues, which Japan has yet to establish. Such organs are independent from the government, composed of lawyers, academics, and officials from nongovernmental organizations, and tasked with investigating rights infractions in the country, securing restitution for them, making proposals to the government and legislature, and carrying out educational outreach on rights issues. Today the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions has members from 118 countries, but Japan is not among them. A bill was submitted to the Diet in 2003 to establish an institution that could join this membership, but nothing became of it; today few in Japan are even aware of the existence of this proposed legislation.

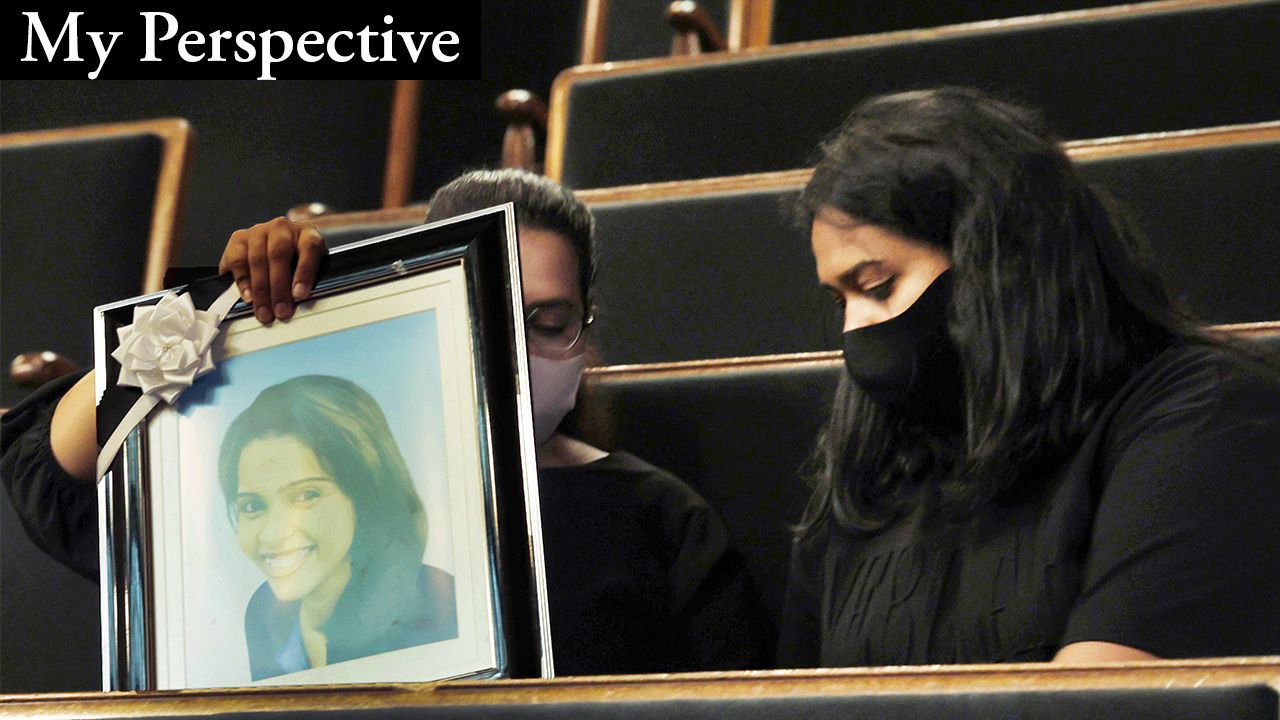

Imagine if such an institution were in place in Japan. The outcome of a host of events could have been considerably different—everything from the death of Wishma Sandamali, a Sri Lankan held at a Nagoya Regional Immigration Services Bureau detention center, to the sexual abuse of underage boys and young men at the former Johnny’s Entertainment talent management firm and the forcible sterilization of citizens under the Eugenic Protection Act in effect up through 1996.

“Human rights” is a key term for navigating contemporary society. I feel that the attention focused on the rights situation in Japan by the international community is harsher than most Japanese understand it to be. The nation’s current administration has delivered wishy-washy messages on human rights issues; it is my hope that those politicians looking to replace Kishida in the prime minister’s seat will avoid making the same mistakes he did and make the effort to close the gap between the Japanese and international situations.

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Poornima [at left] and Wayomi Sandamali carry a photograph of their deceased sister Wishma on June 9, 2023, as they witness the passage of the amended Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act in the National Diet, Tokyo. © Jiji.)