Living with the Reality of Dementia

Dementia Is Not the End: A Neuroscientist Finds Hope Caring for Her Mother

Health People Society Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Not Wanting to Accept Dementia

Onzō Ayako first noticed changes in her mother, then aged 65, in 2015. There was a series of incidents, such as when her mother went to the convenience store to buy miso and returned empty-handed. It was so out-of-character for such a conscientious, stable person.

For some reason, she was hesitant to take her mother to see a doctor, holding off for a year. According to Onzō, “I kept telling myself, ‘These things happen to everyone.’ I didn’t want to accept that she was unwell.”

Meanwhile, she grew annoyed with her mother’s many blunders, and scolded her increasingly. Onzō now regrets her behavior. “Because I chastised mother so much, she lost her confidence. Even though I delayed having her diagnosed with dementia, if I had treated her as though nothing mattered, it would have been completely different later.” At times, her mother just stood there in a daze.

“Dementia” is a word that hits hard. Even as a neuroscientist, she did not want to admit that this was affecting a member of her family.

Making Miso Soup Together

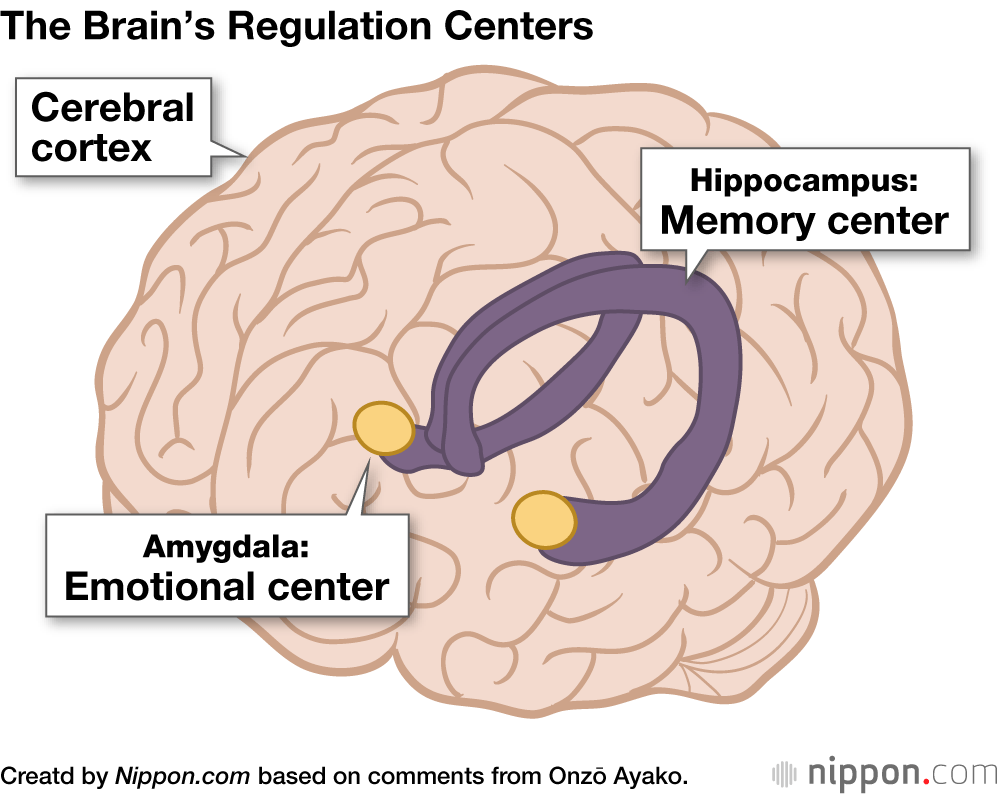

When Onzō finally did take her mother to a doctor, a magnetic resonance imaging scan revealed that her hippocampus, a part of the brain that controls short-term memories, was shrunken. She was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia. Her mother was dumbstruck when she heard the diagnosis, but as a neuroscientist, Onzō realized she had to face reality, and resolved to do so.

She regained her level-headedness, telling herself: “It’s just a little damage to the hippocampus. The other areas of her brain are fine, and there are various things we can do about this. It’s not like she’ll immediately be impaired.”

The first action she took was to establish a new routine: making miso soup with her mother. When the hippocampus is damaged, it becomes hard to recall things that just happened. For example, if you are making soup, partway through, you may forget what you are doing, and become unable to continue. But her mother was still able to use a knife deftly to peel vegetables and so on.

“When making soup together, I played the role of her hippocampus,” says Onzō. (© Hanai Tomoko)

“Physical skills are not lost, because these are controlled by parts of the brain other than the hippocampus,” Onzō explains. “Whenever mother said, ‘What was I doing just now?’ I’d just remind her we were making soup, and we’d continue. I played the role of her hippocampus.” She recounts that her mother’s condition did not worsen rapidly, and she managed to sustain their soup-making team efforts for three years.

Song Quiz Champion

The care required for her mother gradually increased, though, and for some time she attended a daycare service. Finally, in 2021, she was diagnosed with severe dementia.

Onzō tried to use musical therapy, since her mother loved music, and had even been a piano teacher. She invited a therapist to their home, and the moment they began to play the piano, “Mother instantly began to sing along, with perfect recollection of both melody and lyrics,” Onzō recalls. “Usually, people with severe dementia have trouble even forming words.” In fact, music is not related to the hippocampus, but a different area of the brain that is not generally affected by dementia.

Even though a person with a shrunken hippocampus has no memory of the most recent things, they can remember things from long ago, when their emotions were deeply active. Memories of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, which Onzo’s mother recalled as “scary,” were deeply engraved in her memory. At other times, she would sometimes strangely ask, “Where is the little one?”

At that time, Onzō had lived with her mother and father, with no young children. “When I paid close attention, I noticed she would often say this when she was having a meal. It seemed that she was looking for a child to feed. In fact, she was thinking of me when I was little. I realized it was her motherly instinct to feed her child.” Memories of the family eating together at the dining table seemed important to her.

What Remains Is Emotion

When someone is affected by dementia, slowly but surely, their capabilities decline. But Onzō emphasizes, “Not all of their cognitive functions weaken. The ability to feel emotions remains.”

To understand the mechanism of human emotions, imagine encountering a snake-like object on the roadside—most people would instinctively jump. As Onzō says, “Momentarily, you flinch, breaking out in a cold sweat, which stems from the emotion we call ‘fear.’ After that, the cerebral neocortex realizes that it wasn’t a snake, but just a piece of rope.”

This reflexive physical reaction is due to a survival instinct, which all living creatures have to protect them from predators. But in the case of humans, physical reactions “don’t just ensure our survival, they are also related to our emotions. This includes a wide range of emotions, like love, self-esteem, and likes and dislikes.” The part of the brain related to physical reactions is resistant to atrophy, and therefore we tend not to lose our emotional faculties.

Not the End

In Japan, it is estimated that over 10 million people have dementia or mild cognitive impairment, a potential precursor. The causes of the disease are not fully understood, but according to Onzō, in the same way that fatigue-causing lactic acid accumulates when you use your muscles, the operation of neurons in the brain produces waste substances.

“Our brains expel this waste naturally, but it’s believed that if the speed of disposal can’t keep up, we’re left with excessive waste, which can damage the neurons.” Apparently, this waste tends to build up more as we age.

She recommends walking or similar light exercise as a preventive measure, and explains that, at present, there is no wonder drug for treating dementia. She stresses: “We need acceptance, beyond simply prevention and cure. There are other options besides giving up. It’s important that our approach recognize the value of people.”

People with dementia harbor concerns they cannot share even with their families. Aside from going between home and care facilities, it is important that they have opportunities to interact with other people suffering from dementia. “It’s easier to talk with others in the same situation. When they face troubles, more experienced dementia patients can lend an ear and give advice. That’s something family can’t really do.”

Onzō maintained her belief that her mother was the same person she had always known and loved until she passed away, in May 2023, at the age of 72. She recalls that her mother hummed her favorite tunes right up until the day before she died.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Neuroscientist Onzō Ayako. © Hanai Tomoko.)