JFL Today: Considering Japanese-Language Education for Foreign Residents

Giving Foreign-Roots Children a Leg Up in School: NPOs Active in Language Education

Society Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

High School Out of Reach

Most children in Japan with foreign national roots are here because their parents, or others in their family, have come to the country to live or work. Once those children have become settled and acquired some Japanese-language proficiency, they think about their next steps: wanting to go on to university, or aiming for a profession, like schoolteacher or engineer. To put those dreams within reach, it is essential for them to progress beyond compulsory education to senior high school, and then on to university. But a formidable hurdle awaits in the form of entrance exams.

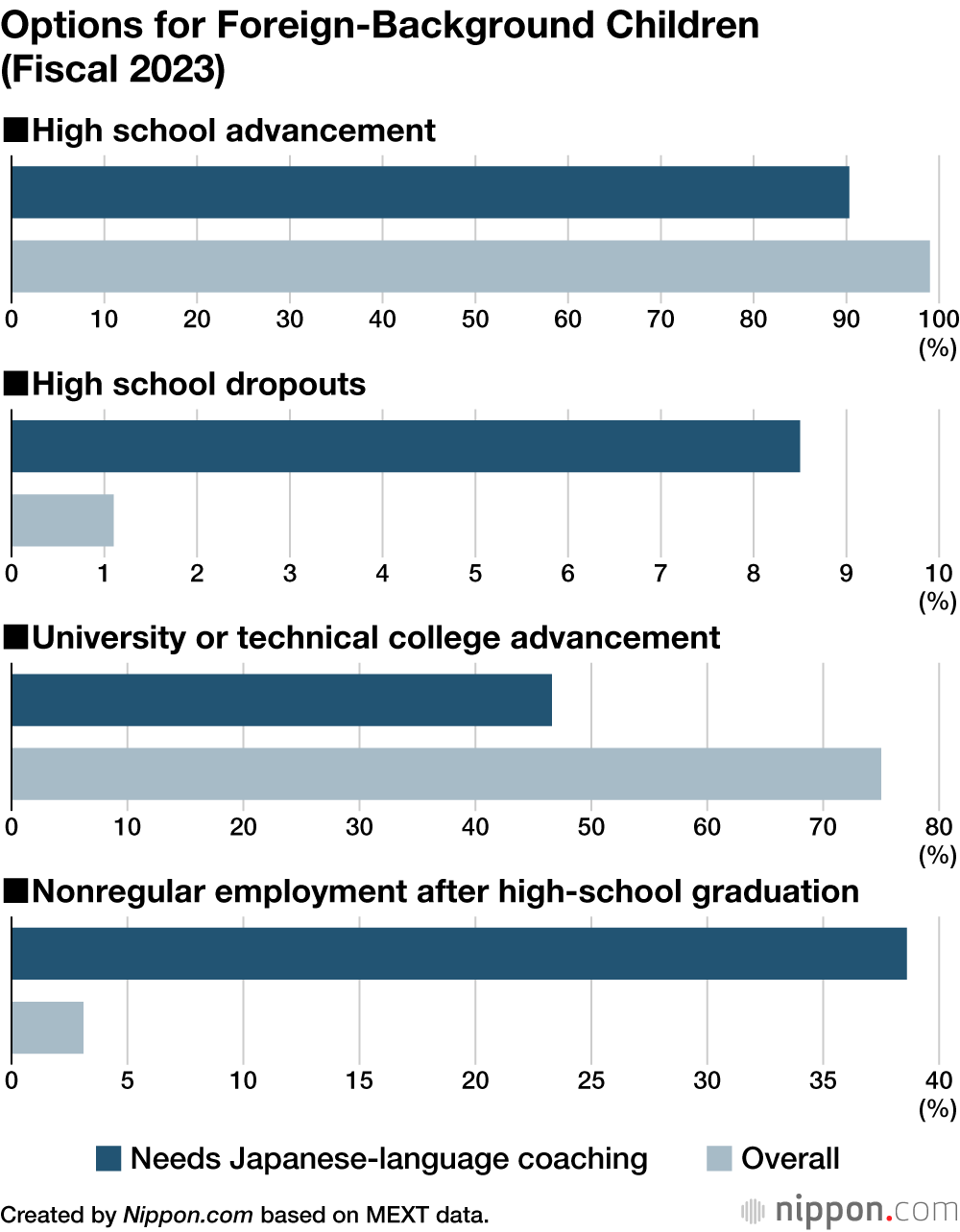

In a fiscal 2023 survey by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) among junior high school students who are not fluent in everyday Japanese and thus need additional language coaching, the rate of advancing to senior high school is around 90%, markedly lower than the nearly 100% achieved by their native Japanese-speaking peers. Many such students, regardless of their inherent capabilities or aspirations, cannot enter the high schools they were aiming for, and instead proceed to night school or lower-level high-school programs where student intake has fallen below quotas. Lack of more advanced Japanese is what holds them back.

Pronounced Weakness in Japanese for Learning

High-school entrance exams require understanding of subject matter taught in relatively advanced Japanese, along with the ability to express oneself competently in the language. Foreign-background children need coaching in this area; in subjects like math and science, they may grasp the source material just fine, but misunderstand exam questions because of insufficient Japanese ability. But the level of Japanese instruction such students receive in junior high school is often not enough to help them with high school entrance exams. That is because the sort of Japanese they are taught—for example, “I have a headache,” or “Where is the toilet?”—is only adequate for daily life. Compounding the issue is that many teachers are not specialists in teaching the Japanese language, so there are wide variations in the quality of instruction.

In junior high school, students attend school 35 weeks out of the year; a schedule including six hours of focused Japanese-language study per week amounts to only around 200 hours of classroom time per school year. Given that people from abroad who intend to study at Japanese universities spend two years attending Japanese-language school prior to taking entrance exams, matching that amount of time is basically impossible for these full-time students. Even if they participate in after-school programs to improve their language skills in preparation for their entrance exams, it will likely not be enough for students who come to Japan as young teens. Some of them need to take a gap year before trying to enter high school.

The Internationally Recognized Right to Learn

The case for providing support in Japanese to these children is clear. Under the International Covenants on Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Japan has ratified, the government undertakes to provide equal study opportunities to all children, regardless of nationality. In other words, the government has committed to providing children with compulsory primary education in elementary and junior high schools and opportunities to receive secondary education in high schools.

Japan welcomes foreign workers to supplement its labor force, granting them work visas, and also admits their children as part of their families. Thus, as long as foreigners come to Japan in response to the country’s labor needs, the government should do all it can to enable foreign children to receive an education in Japanese. Support is needed all the way through high school, as in this country, lack of a diploma at that level severely restricts job prospects.

A Japanese lesson at the YSC Global School. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

In 2020, MEXT requested that each prefecture’s board of education institute special quotas for foreign students or add phonetic syllabary to questions on high school entrance exams. High school (from tenth grade on) is not compulsory education, but the ministry made this request to level the playing field as much as possible, to allow all students to demonstrate their capabilities. Although more and more prefectures have adopted quotas for foreign children, a private sector study indicated that, as of fiscal 2024, approximately half the prefectures had yet to do so.

High School Dropout Rate Eight Times Higher

Even if successful in passing a senior high school entrance exam, foreign students still face difficulties. The Japanese language continues to be a barrier, as lessons include even more specialized or abstract vocabulary than in earlier schooling. Beginning in fiscal 2023, for foreign students MEXT has allowed Japanese-language classes to make up around 30% of the credits needed for graduation.

In Tokyo, some schools with foreign student quotas—mainly at the senior high level—give credits toward graduation for classes in Japanese as a foreign language. At night schools and other institutions, many teachers are very dedicated to having all their students learn. They work hard toward this goal, but in reality, many institutions lack the time or personnel to accomplish this. Leaving this task up to schools or individual teachers creates difficulties for all the students, Japanese and foreign alike. Correspondence or night courses need to offer a much more extensive Japanese-language curriculum.

Falling behind in classwork due to insufficient comprehension of Japanese, some foreign-background high school students feel more comfortable outside school, working a part-time job and the like, and either fail a year or drop out of school. According to MEXT, in fiscal 2023, some 8.5% of students needing coaching in Japanese had dropped out of high school; this is eight times the average rate for all students at that level. To reduce this figure, initiatives to prevent isolation at school and recognize differences are important. It is also vital to improve such students’ attitudes, so as to stimulate a desire to learn and help them feel positive about themselves.

Challenges in Accessing Tertiary Education

Japanese-language ability also has an impact on students’ future after high school. As of fiscal 2023, only 46.6% of high schoolers needing support in Japanese progressed to universities or technical colleges, a figure 30 points lower than the average for all students.

There are a variety of ways for foreign students to enter university or technical college, such as exams for candidates recommended by school principals, foreign student quotas, and other programs offering slightly prioritized routes in. However, information about which schools offer which types of special exams, Japanese proficiency levels expected, and so forth is difficult to come by, leaving many students in the dark about the subjects they should study and how to do so effectively. For example, some universities require a passing score on Level 2 of the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test—a level of Japanese sufficient for understanding the news—as a prerequisite for applying. But this is often not sufficiently well known, meaning that students cannot prepare adequately; as a result, some abandon the idea of going on to tertiary education.

Japanese-language textbooks developed for foreign-background students. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

Help from Civic Groups

Civic groups play a major role in supporting this diverse population’s learning. There are volunteers and NPOs active across Japan providing the extra coaching in language for learning that schools alone cannot adequately provide.

The YSC Global School, with which I am involved, focuses on teaching Japanese for learning, supporting children in acquiring the vocabulary they need for keeping up with classes in all subjects. Approximately 350 students ages 6 through 18 attend after school or on weekends to acquire Japanese proficiency that will allow them to advance to higher education or employment. YSC believes that providing a place where students can learn in a comfortable environment, including psychological support and career counseling, will stimulate their desire to learn. A growing number of junior and senior high schools have been reaching out to us in recent years for input on ways to support their students.

Language Proficiency as a Key to Japan’s Future

Guaranteeing foreign-background children’s right to learn is necessary because Japan is a signatory to international conventions. More importantly, though, it is a way to maintain our society’s future vitality. If these children receive appropriate education, they will understand Japan’s culture more deeply, ultimately becoming productive members of society who can help to relieve the labor shortage while paying taxes and social security contributions. If they do not, they will find it hard to fit in, fail to adapt to Japanese society, or end up returning to their home countries. According to MEXT, nearly 40% of high school students who need coaching in Japanese go on to nonregular employment, a figure 10 times higher than for all senior high school students. Providing adequate coaching would help promote social cohesion too.

The central and local governments need to provide adequate staffing and funding for Japanese-language education in schools. The school environment should be predicated on diversity, with all children learning on an equal footing and foreign-background learners not treated as special cases. Providing appropriate support will help them to thrive as members of society.

More and more young people from diverse backgrounds are expected to live in Japan as the technical training systems and other work opportunities allowing workers to bring in their families are broadened. Realistically-speaking, it is clear that Japanese-language education provision must expand to accommodate those children. In Japan today, a growing foreign population is a reality, and it is important to think of how the attitudes of Japanese people toward these children can be changed. It is a test for all of us.

YSC Global School’s Tanaka Iki speaks with Nippon.com. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

(Originally published in Japanese, based on an interview by Matsumoto Sōichi of Nippon.com. Banner photo: A classroom at YSC Global School, where children with foreign roots learn. © Matsumoto Sōichi.)