An Honest Look at Matsumoto Seichō, Japan’s Master of Detective Fiction

Books Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

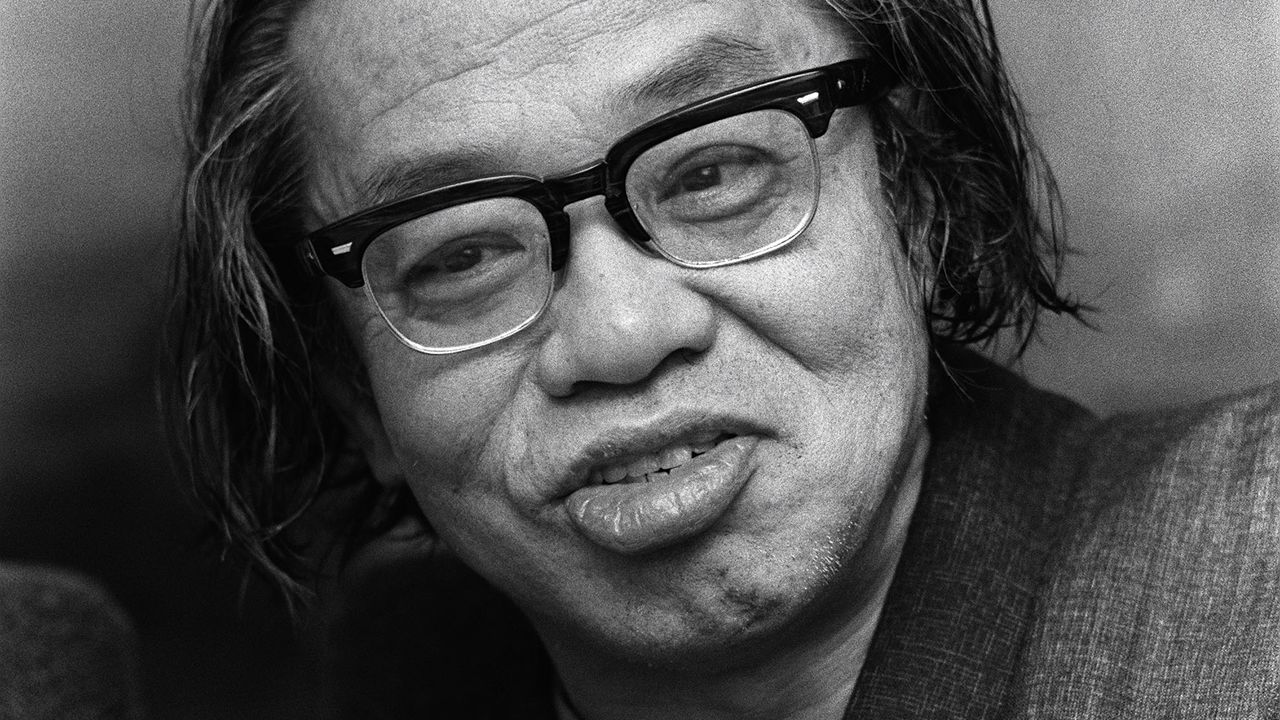

Matsumoto Seichō was born in the town of Kokura in northern Kyūshū on December 21, 1909. He is commemorated by a museum in the town of his birth (now part of the Kita-Kyūshū conurbation). Among the exhibits on display is the unfinished manuscript of the novel he was working on when he died: a mystery set in historical times that turned out to be the last piece on which I collaborated as his editor at Shūkan Shinchō.

On April 20, 1992, Matsumoto collapsed at home from a brain hemorrhage. He was rushed to the hospital, leaving his favorite Mont Blanc fountain pen and the manuscript he was working on abandoned on his desk. He underwent successful brain surgery, but while he was in the hospital doctors discovered signs of advanced liver cancer, and he died on August 4 that year. He was 82.

No Vacation from Writing

At times, one of us in the office would pick up the phone at work to be greeted by a gruff voice announcing: “Hello, Matsumoto speaking.” It’s not an uncommon name, and in another context one might have expected the caller to identify himself a little more precisely. But he never bothered to say anything more than his family name. In any case, his distinctive, gravelly voice was enough for anyone in the editorial department to know instantly who was on the other end of the line. Certainly, it wasn’t a good idea to ask for more detail. If pressed to identify himself in clearer terms, he was liable to fly off the handle. “I just told you: Matsumoto. Don’t you know who I am?” He was one of our regular writers, and one of the most important. It stood to reason that for us, the only Matsumoto who mattered was Matsumoto Seichō. He published 14 serialized novels with us before he died. I worked with him as his editor on three of them, starting in September 1983.

He used to call at any time of day or night when he had something he needed to talk about or wanted to issue a summons to his editor or other employee. It was an article of personal faith with him that “there is no vacation from writing.” He used to devote himself to his work, apparently hardly ever stopping to rest or sleep. And if a writer has no holidays, then his editors must expect to work around the clock as well. I used to hurry out to his residence in Suginami,Tokyo, whenever I got the summons over the phone.

He often wrote through the night. I’d be shown into a room downstairs to wait, and after a few minutes the great man himself would suddenly appear with manuscript in hand. He’d plop himself down on the sofa, his hair bedraggled and his kimono starting to come undone, looking for all the world as he’d just this minute finished an all-night writing session.

He would hand me his manuscript then close his eyes and light a cigarette. His breath heaving slightly, he would smoke the cigarette right down to the filter, so that I sometimes worried that he might singe his fingers. The ash would fall into his lap but he didn’t seem to notice. His clothes were always pockmarked with holes from cigarette burns.

While he smoked, I would start to look over the manuscript he had just given me. For any author, it’s the moment of truth, when he hands over a manuscript and asks: “What do you think?” An editor is a writer’s first reader. If I tried to wriggle out of saying what I thought by giving some noncommittal reply, he would tell me bluntly: “Call yourself an editor? You’ll have to do better than that!” He always wrote with his audience in mind, and took his responsibility to the reader seriously.

His stories always featured at least one of the unpredictable twists he was famous for. On the rare occasions when I made a perceptive comment after reading the manuscript, he would give me a broad grin: “Ah, you got it? What do you think? Not bad, eh?” His smile reminded me of a child who had been caught playing a delightful prank on the grown-up world. He seemed delighted to know that his writing had hit the target.

The Importance of Motive

“Motive: that’s what interests me,” he often used to say. Analyzing the reasons that drove people to commit a crime, and getting them down convincingly on paper—this was what he found interesting and rewarding in his work. Relying on cobbled contrivances to tie things together, he used to say, struck him as pointless and uninteresting. It was this emphasis on motive that enabled him to portray human characters and actions with such depth, and made his stories resonate so strongly with readers.

When I knew him he was already in his mid-seventies, but the stories he wrote for our magazine always dealt with up-to-date and even cutting-edge topics. He was never complacent to sit back and soak up the praise for the work he had already done. He had a strong pride in his craft as a writer, and an insatiable drive to keep on creating. He always kept a close eye on the latest developments in international mystery writing.

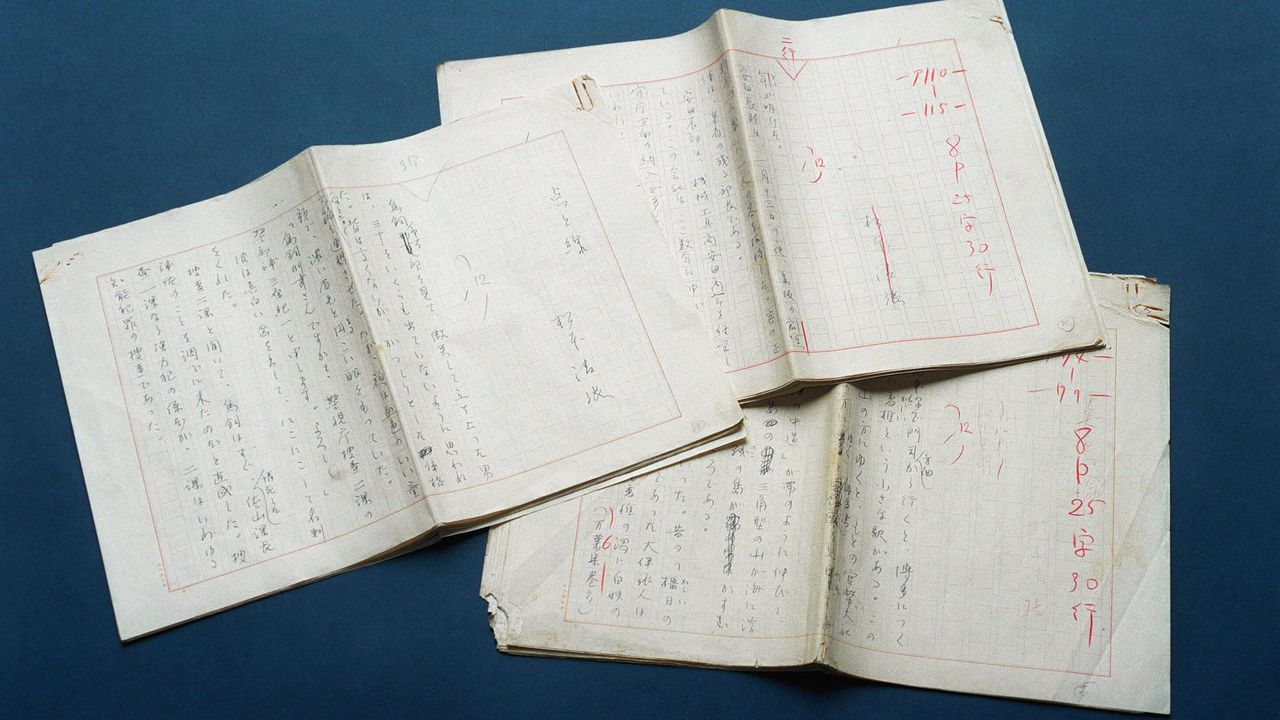

The original manuscript of Points and Lines, Matsumoto’s best-known novel. (© Jiji)

The first novel I work on with him with was Seijū hairetsu (Array of Sacred Animals), an international thriller dealing with a political summit between the United States and Japan, and secret Swiss bank accounts. Publishing legend has it that Matsumoto’s descriptions of the layout and interior of the Akasaka Palace in Tokyo—a state guesthouse where visiting dignitaries are hosted—were uncannily accurate enough to cause amazement and alarm among the security detail within the Tokyo Metropolitan Police. The novel features a boldly conceived scene in which a Japanese woman sneaks into the palace for a secret rendezvous with the US president. Only a skilled writer like Matsumoto could have pulled off such a plot and made it convincing.

In fact, by this stage, he already had ideas for his next work, which was going to involve De Beers, the international diamond company. The novel would show how De Beers and its Rothschild backers had controlled every stage of the diamond production process from London in the early twentieth century, from the mines in South Africa to the manipulation of global market prices, until the discovery of vast untapped diamond mines in Australia threatened to end the De Beers monopoly. Matsumoto planned a novel of intrigue involving Japanese interests caught up with big finance and the global diamond industry.

Eventually, the preliminary background research on the novel took longer than Matsumoto had budgeted for. He decided to put off writing the De Beers novel while he reorganized his ideas. The idea he had for his next project was quite different: the historical mystery set during the Edo period (1603–1868) that would ultimately be left unfinished at his death.

I remember how enthusiastic he was as the serialization got underway. “I want to make this the best thing I’ve ever done,” he said. He felt that a lot of modern novels set in feudal Japan were insipid and lacking in interest, and was determined to put things to rights with a masterpiece.

“I Don’t Have Much Time”

Matsumoto was notorious among his editors for never delivering his manuscripts until the last minute. But on this final story, installments were always ready a whole week before they were due. The pages of his manuscript, written in fountain pen, were crisscrossed with corrections and revisions, with new ideas scribbled everywhere in the margins.

He would continue to revise until he was satisfied—even after we had sent out the proofs. He was meticulous and absolutely determined to make the story as good as he could make it. Time and again, the proofs would come back covered in corrections.

“I don’t have much time,” he often used to say in those days. The sense of responsibility he felt to his craft was palpable. He used to mention a well-known writer whose name had been mentioned as a candidate for the Nobel Prize, and say: “He almost gave up writing altogether. But I’m going to keep going till the end.”

He was certainly never in awe of a writer’s reputation. I remember him once referring to the Sea of Fertility, the four-part magnum opus that Mishima Yukio completed just before his flamboyant suicide. “The whole thing’s a total failure,” he said. I was so taken aback by the vehemence with which he had spoken that I didn’t think to ask him why. I regret it to this day; I’d love to have known his reasons.

He often used to fret about how many more books he had left in him to write. The first installment of this final serialization ran in the New Year double edition that went on sale at the end of 1991. I received the manuscript for the second installment early in the New Year, on January 3.

Matsumoto’s eldest son Yōichi and his wife offer flowers at Matsumoto’s memorial service, held on August 10, 1992. (© Jiji)

This time the phone call came to me at home. I went over to his house in the early afternoon. After I’d been waiting for a while, he appeared with his manuscript in his hand. His first words to me were: “I worked on it all night on New Year’s. Didn’t even watch the Kōhaku song contest on TV.” I was moved by his obvious dedication to his work. He had obviously spent days at his desk through the holidays.

The Sudden End

On the morning of April 21, 1992, one of his relatives got in touch to tell me that Matsumoto had been hospitalized. He’d been taken ill the night before, after returning home from a function. It was so sudden I could hardly believe it. I had called him the previous afternoon to report on something he’d asked me to research for the story he was writing. I hadn’t noticed anything unusual in his voice then. “I have to go out for a while this evening,” he said. “Maybe you could bring the materials over tomorrow?” This brief exchange turned out to be the last conversation I ever had with him.

Even during his final illness, writing continued to occupy his thoughts. One day his family faxed me a hastily written note he had scribbled to me from his hospital bed. It seemed to be instructions for future developments in the novel we were working on together, but his shaking hand made the handwriting impossible to decipher.

What plans did he have for the rest of the story? He never revealed how his stories would pan out, not even to his editors. If ever I asked how things were going to develop, he would flat out refuse to answer: “I can’t tell you that.” He liked to keep things mysterious. He wanted to see the reaction when his editors read the story for the first time. He didn’t want to spoil the surprise. The reader’s reaction was the most important thing of all.

That serialization I helped him with in the last months of 1991 was unfinished when he died and never appeared in its intended form. It is not included in his collected works. In December 2009, a special edition of Shōsetsu Shinchō came out to mark his centenary—the only time the 300 pages or so of manuscript he had written before his untimely passing have ever been published. Sadly, the world will never learn what was supposed to have come next.

Matsumoto Seichō

Matsumoto Seichō was one of the widely read Japanese writers of the twentieth century. His early story “Aru Kokura nikki-den” (Legend of the Kokura Diary) won the Akutagawa Prize for emerging writers in 1953. He shot to popularity with a series of detective novels that tackled the darker side of contemporary society, the best known of which include Ten to sen (Points and Lines) and Suna no utsuwa (Inspector Imanishi Investigates). His writing covered a wide range of genres, including nonfiction books like Nihon no kuroi kiri (Dark Fog over Japan)—which probed some of the scandals and unresolved crimes of the postwar occupation period—and numerous historical novels. Over the course of a 40-year career, he published more than 1,000 stories and other pieces. His works, shot through with a strongly anti-authoritarian streak, continue to be popular with readers of all generations today, nearly 30 years after his death.

(Originally published in Japanese on April 5, 2019. Banner photo: Matsumoto Seichō in 1971, aged 61. © Jiji.)