A Senior Lifeline: Shuttle Service for Elderly “Shopping Refugees”

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Elderly Lifeline

“Hello. Oh, Yamada san. I’ll be right there.” Hanging up the phone, a volunteer hurries from a community gathering space inside the shopping area of the Murayama public housing complex, hops into a three-wheeled pedicab—not unlike an auto rickshaw seen abroad—and heads directly to the elderly caller’s home.

Powered by an electric motor, the vehicle seats two people in the front with a section for baggage in the rear. Volunteers are on duty weekdays from 10 am to 3 pm, and residents can call anytime during operating hours for a free pickup and return.

June 14 is pension day and the shopping precinct is busier than usual. At the community hub, 82-year-old Hinata Hideko climbs into the pedicab after finishing her grocery shopping. “They’re my wheels,” she jokes. “I used to ride my bicycle here, but since I started having trouble with my legs five years ago, I’ve relied on the shuttle once a week.” Before, Hinata struggled to get her heavy shopping bags home, but she finds the service a huge help because, unlike the bus, it operates door-to-door.

The Murayama apartment complex was completed in 1966. In the early years it bustled with young families, but over the decades residents have aged and the children born here have grown up and moved out. A survey of the complex found that as of 2018, over half of inhabitants were aged 65 or over.

Since 2000, residents have gradually relocated from dilapidated older apartments to newly built units. However, many of these blocks are located 750 meters or more away from shops, and senior residents now must walk 20 or 30 minutes to do their shopping. The local chamber of commerce and industry initiated the pedicab service in response to elderly residents who were no longer able to make the journey to the stores—such “shopping refugees” are on the rise as Japan ages.

The local council provides financial support, and a dozen or so auto-related firms that have remained since the local Nissan Motor plant closed in 2011 also cooperated in the project. Since its launch, the service has become a lifeline, with close to 200 people using it each month for shopping as well as trips to the doctor.

A Sense of Crisis

Clothing store owner Hiruma Seiichi is the man behind the Murayama complex shuttle initiative. Noticing the growing number of elderly residents no longer able to access the shopping arcade, he felt a crisis was looming. At first, he and other shopkeepers made deliveries, but it quickly became apparent that many older customers were isolated at home and needed more than just a box of groceries. When he noticed a lady using a taxi to get to the shops, it dawned on him that what she and other elderly residents were missing was the stimulation of visiting the shopping arcade. With this realization, retailers launched the pickup and drop-off service in 2009.

The Murayama complex is located along the commuter belt that stretches west from central Tokyo. Just 50 minutes from Shinjuku Station on the Seibu line, it was one of several mammoth public housing projects built to accommodate the influx of young workers from Japan’s rural areas during the nation’s era of rapid economic growth. The complex boasted more than 5,000 units when it opened. Hiruma, who set up shop here in 1972, says those early days are still etched in his memory.

“Back then, I could order a truck full of stock and be sold out within a week,” recounts Hiruma. It was an age when wages were on the rise and Japan’s population was growing. Hiruma recalls that the New Year’s Eve sales were especially lucrative and could see the shop turn over as much as ¥1.2 million in a single day. A picture of the complex’s fifteenth anniversary celebrations in 1981 shows a sea of children, attesting to the youthful vigor that existed. Forty years later, though, there are far fewer young families living in the complex.

Children crowd together during a celebration in 1981 (left). Today, the complex has few young residents.

The shopping arcade’s customer base is now largely seniors on fixed incomes. The encroachment of large retail outlets has disrupted prices, worsening the business outlook for local shop owners. When sales started to plunge from around 2000, Hiruma and his fellow retailers stepped into action to entice the seniors to their stores.

Hiruma recognizes there are limits to focusing on elderly shoppers. While the number of regular shuttle users has grown over the years, higher mortality among the older demographic means that ridership has reached its peak. “The best store owners can do is maintain current sales levels,” he explains. “If we’d done nothing, though, our revenues would have continued to tumble.”

Looking after the Community

In addition to running his store, Hiruma himself is on standby at the shuttle station two days a week. Along with ferrying riders to and from shops, the service also monitors the wellbeing of seniors, and volunteers will alert the city’s aged welfare support center if they notice someone has been out of touch for a while. Hiruma has been running his shop for almost 50 years and says helping run the shuttle is a way to give back to the residents who have supported him over his career.

The shuttle initiative has attracted attention from other public housing complexes around Japan that also have rapidly-aging residential populations. In the last 10 years, 85 different groups have visited the Murayama complex to see how the program is working, with several starting their own services.

According to Miyagaki Jun’ichi, head of the Economic Research Department at the Nippon Life Insurance Research Institute, the key merit of the shuttle service when compared to home delivery and mobile shopping services is that it helps sustain seniors’ mental health by ensuring they get out of the house, talk to people, and enjoy the shopping experience. However, he notes that as it does not fit into a commercial model and must rely on motivated volunteers to keep it going.

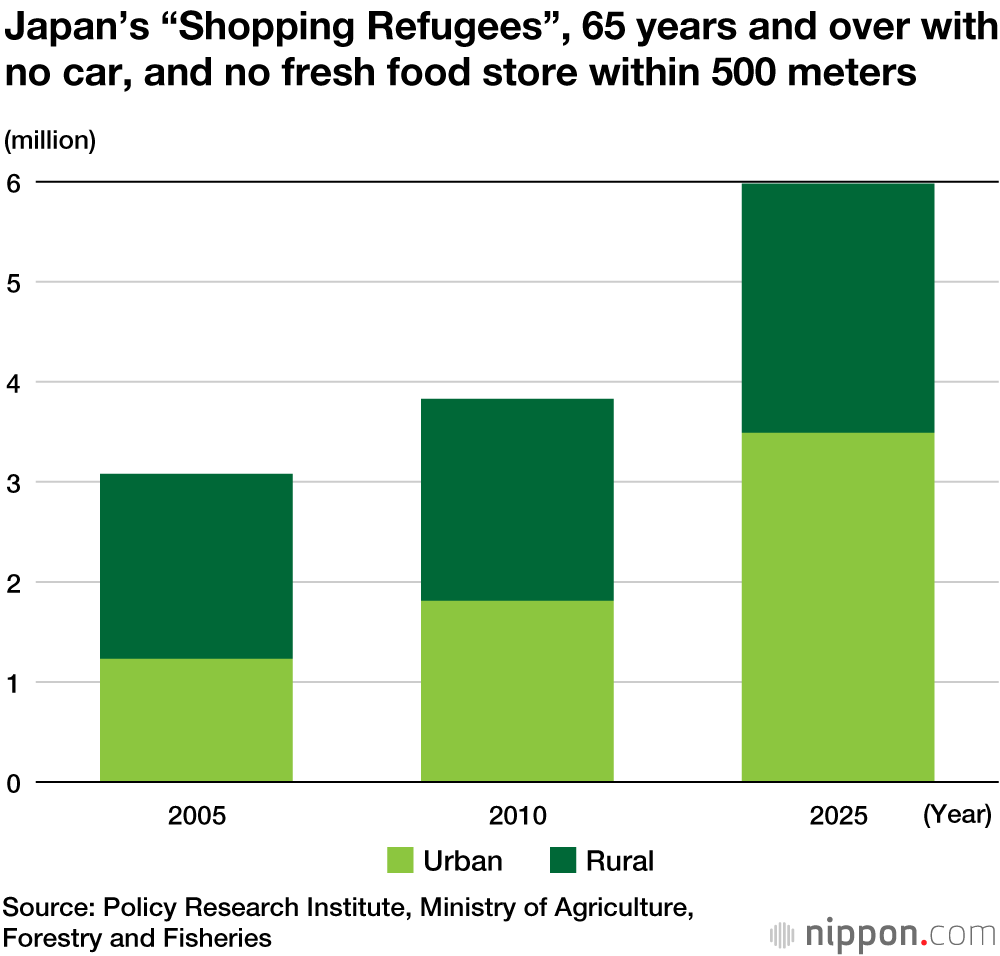

A report by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries found there were over 3.8 million people in Japan 65 years or older without a car and with no grocery store within 500 meters of their home. It forecasts the number of such “shopping refugees” to rise to nearly 6 million by 2025, with the phenomenon increasing mainly in urban areas with rapidly aging populations.

Miyagaki counts the residents of the Murayama apartments lucky as their shopping center is still in business. Depopulation and the rise of large-scale supermarkets have forced local shopping arcades in provincial cities across Japan to close at an alarming rate. Some municipalities have responded by offering government-subsidized community bus services for residents who must travel further to shop, but Miyagaki notes that every location is different and solutions must be tailored to suit local circumstances.

Question Mark over Survival

Although the shops at the Murayama apartment complex have benefitted from the shuttle service, infrastructure like gas and sewage lines are rapidly deteriorating, and it is just a matter of time before it will face the wrecking ball. The Tokyo metropolitan government’s Office for Housing Policy says it will take into account the intentions of shop owners before deciding whether to rebuild the arcade in a new location, but a decision is still pending.

As a public housing facility, the Murayama complex gives priority to low-income earners and the socially disadvantaged, and elderly residents are likely to remain the largest percentage of residents for the foreseeable future. Hiruma remains confident that even if no one from the local populace chooses to take his place, people from outside can be recruited to keep the arcade and shuttle service operating. Shop owners and residents alike are anxiously awaiting the Tokyo metropolitan government’s next move and remain hopeful that there is the political will to make communities like the Murayama housing complex truly senior friendly.

(Originally written in Japanese. Reporting and text by Mochida Jōji of Nippon.com.)