Inclusivity a Distant Target: Challenges Presented by the Tokyo Paralympics

Society Tokyo 2020- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Email from a Disabled Swimmer

In September 2018, I received an email describing an unfortunate incident that took place at the Japan Masters, an annual nationwide championship for older athletes. Part of its stated mission is to promote an inclusive society and competitions are open to athletes with disabilities.

The email I received concerned the Masters swimming championship. Its author, a swimmer who has only one forearm, was suddenly informed that participants in the freestyle event would be disqualified if they did not touch the end of the lane with both hands. The athlete and her association lodged a protest with the Japan Swimming Federation but they were initially unable to overturn the decision. The JSF cited the fact that the Masters competition was governed by its rules, which were in turn based on the regulations of the International Swimming Federation, an organization for able-bodied swimmers.

While this was not the first incident of its type, protests by other athletes in the past had been unsuccessful in bringing about change. The swimmer involved this time, an athlete with experience in international competition, subsequently lodged complaints with various authorities and eventually secured an exemption to the two-hand touch rule. While this represents an improvement, the athlete still had to resort to obtaining a special exemption to be allowed to compete.

A Paralympic Promise

On December 6, 2018, Olympic Organizing Committee Chairman Mori Yoshirō issued a declaration that pledged that the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games would be a catalyst for helping those with disabilities to feel a part of society. The Games’ vision calls for unity in diversity and declares that society makes progress when it affirms and accepts differences in race, gender, sexual orientation, language, religion, political views, and disability status. The Basic Plan for Tokyo 2020 includes a statement that the Paralympics will leave a legacy of changed attitudes and acceptance of people with disabilities, showing that the Organizing Committee positions the Paralympics as important.

Despite this, preparations for 2020 have betrayed much that goes against inclusivity, both in terms of infrastructure (for example, accessibility) and in terms of more intangible elements, like attitudes to the disabled. I believe that this is what made Chairman Mori reiterate his commitment.

A History of Exclusion

Let us consider why so much use is being made of the term ”inclusivity” in the lead up to the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games. Answers can be found by looking into Japan’s past. According to a 2010 report issued by the Central Council for Education, a body under the auspices of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) it was the enactment of the School Education Act in 1947 that for the first time gave children with disabilities the opportunity to receive an education, albeit in the form of “special education”, separated from their able-bodied peers. As late as the 1970s, schools for disabled and able-bodied children were generally segregated, a contrast to the mainstreaming approach that was prevalent overseas. The report states that even after Japan ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons for Disabilities in January 2014, disabled and able-bodied students remained segregated.

In the area of welfare as well, it was only after 1981, the International Year of Disabled Persons, that reforms were carried out to replace institutionalist laws with legislation that encouraged those with disabilities to become a part of their local communities. And It was only five years ago—four months after Tokyo won the bid for the Olympic Games, in fact—that Japan finally ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons for Disabilities. This all suggests that the term “inclusivity” still doesn’t mean much to the average Japanese.

Getting the Message Across

The commonly used Japanese word kyōsei—rendered here as “inclusivity”—literally means “to exist together.” If this phrase does not evoke a mental picture, it is because it does not spark associations with action. The promotion of coexistence is inclusivity, the opposite of inclusion of course being exclusion. For Japanese people, the description “a society that doesn’t leave anyone behind” may be more evocative.

In a talk on this topic and sport that I gave at a university recently, I urged the audience to consider the issue in terms of whether people were being excluded, and if so, whether there were rational grounds for that exclusion. The audience told me that framing the discussion this way made the issues much clearer.

The Path to the Top is Not Accessible

Japan’s failure to offer inclusive education has had a significant impact on sport. Sport in Japan as we know it developed from physical education offered at schools and universities, in which students are assigned physical activities appropriate to their developmental age. At all levels, sporting activity takes place within a structure of inter-school and eventually inter-collegiate teams. This means that for aspiring Olympic athletes, a pathway to the top is in place so that those who have competed at the national level can reach even further heights.

Historically, Japan did not offer a system of inclusive education that would allow students with disabilities to participate in sport throughout their school years. As a result, while a pathway was in place to train aspiring Olympians, for Paralympians, no such route was available. Even today, it is only in the process of being laid.

Gradual Improvements

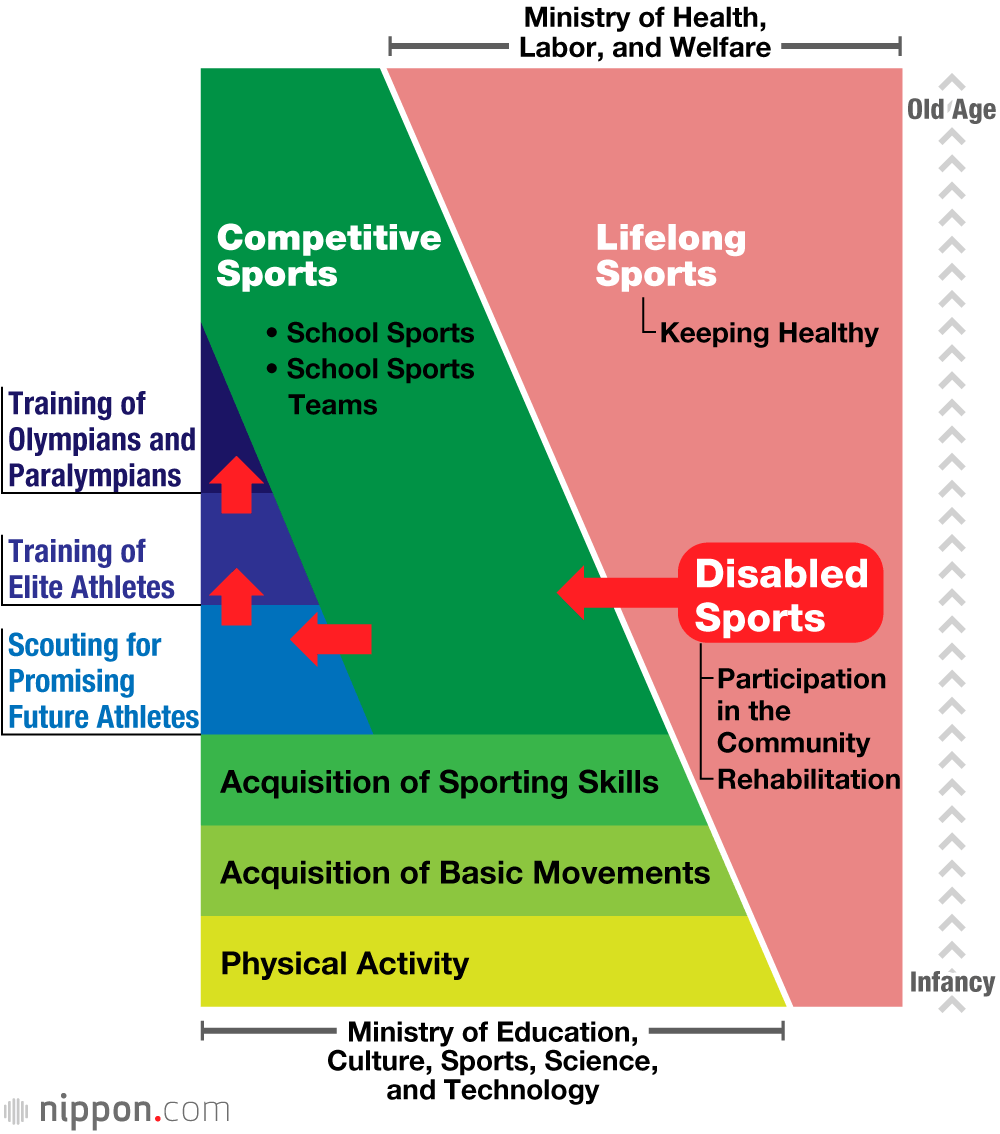

In Japan, disabled sport is the domain of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, and since the 1964 Tokyo Paralympics, disabled sport has been developed as part of welfare policy, with the aim of encouraging the social participation of those with disabilities. However, while nationwide sporting competitions were held with the aim of having those with disabilities participate in society, there was no disabled version of the sports tournaments available to the able bodied. Therefore, because disabled sport was only seen as a welfare initiative, there were no measures in place to nurture aspiring Paralympians. It was only when disabled sport was transferred to the education ministry and, in October 2015, the Japan Sports Agency was established, that standardized disabled sport initiatives began to be implemented. However, at the sporting association level, prefectural level and municipality level, we are far from achieving standardized initiatives.

A survey of disabled swimmers conducted by the Japanese Para-Swimming Federation in 2017 found that only 35% were satisfied with the practice facilities available to them, showing that lack of access to facilities and shortage of coaches remains an issue. Meanwhile, 44% of respondents to the survey said that they had encountered discrimination and prejudice when trying to book practice facilities. Only 52% of respondents had participated in able-bodied sporting events, while 82% of respondents said they believed that disabled athletes should be allowed to participate in able-bodied competitions.

In July 2019, a national training center was opened that gave priority to disabled athletes. However, while Japan now has a facility for those at the pinnacle of sporting excellence, it still offers nothing for training up and coming disabled athletes. You could say that we can see the peak of Mount Fuji but everything below is covered in cloud.

Disabled People Need to Compete Alongside their Able-Bodied Peers

A training publication for Paralympic swimmers gives three examples of athletes born with disabilities who made it to the top level. Their biographies show that they were involved in a variety of physical activities from childhood. For example, a photo of an athlete born without legs shows him trekking with able-bodied children, crawling along the ground with shoes on his hands. We need to provide disabled children with activities suitable for their level of development from childhood. Canada, for example, extends its “Canadian Sport for Life” (CS4L) policy and its long-term talent development model to disabled persons as well.

The diagram below, based on a graphical representation of CS4L, shows how the same concept might be applied in Japan. To have a hope of competing at the highest level, people need to be given access to age-appropriate physical activities from childhood. The white diagonal line in the diagram represents the separation of disabled sport and competitive sport. It was only in 2015, when the Japan Sports Agency was established as an external organ of MEXT, that a path to the top for para-athletes began to be laid.

Can Japan Change?

Let us revisit the incident that occurred at the Masters competition. Based on JSF rules, which are themselves based on FINA regulations, and which require swimmers to touch the end of their lane with both hands, the decision to disqualify the disabled athlete was logically correct. However, the incident also revealed how the system of competition in Japan assumes that disabled athletes will not participate. I believe that the powers that be have yet to realize that they are robbing disabled children, who want to train with able-bodied peers in school sports clubs, of their dreams.

The Masters competition itself did not exclude disabled swimmers. This being the case, the organizers should have thought about how the event could be made accessible to disabled athletes without the need to resort to special exemptions, rather than simply bleating, “but it’s the rules.” An inclusive society means accepting each other. It is this acceptance that spawns innovation and enables Japan to continue to develop in the international community.

In Britain, a disabled sport superpower, university teams get extra points for para-athletes, meaning that universities actively encourage disabled people to compete in sport. Australia, a country that excels at swimming, has allowed para-athletes to compete in able-bodied competitions for some time: an email I received recently advertising an Australian swimming event included a photo of para-swimmers alongside Olympic swimmers. Even the United States Olympic Committee, probably in anticipation of the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics and Paralympics, recently changed its name to the US Olympic and Paralympic Committee. These Western sporting giants exist on a foundation of inclusivity. This should serve as a hint for what Japan needs to do to win a significant number of medals on an ongoing basis.

Japan needs to make the legacy of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and Paralympic games inclusivity through sport. I felt this keenly as I read the email from the disabled swimmer.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 23, 2019. Banner Photo: Para-swimmers compete with able-bodied counterparts for the first time at the Hyōgo Swimming Federation championships in 2019. Courtesy Japanese Para-Swimming Federation.)